The tight leash maintained by the federal government on medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) is finally being loosened in response to the coronavirus pandemic. But as systems change, the clinicians tasked with delivering such medications hold beliefs skewed against treatment that’s established as the standard of care, suggests a nationally representative survey of primary care physicians by Johns Hopkins University researchers.

One in three primary care doctors does not believe that medications for opioid use disorder—particularly buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone—are effective, despite “conclusive evidence supporting continual medication use as the gold-standard OUD treatment,” revealed the study, led by Dr. Emma McGinty and published on April 21 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Reviewing the existing research and knowledge from public health, medicine, nursing and drug user advocacy in a 2019 Consensus Study Report, the National Academy of Sciences found OUD medications to be “evidence based, safe, and highly effective.” That report cast a broad net for its literature review, examining studies going back as far as 1940 and those published in languages other than English.

McGinty and other researchers from Bloomberg School of Public Health and Louisiana

State University Health Sciences Center additionally found that few doctors (just 20 percent) were interested in providing care to OUD patients, or in increasing their access to substitution therapies like buprenorphine and methadone by way of policy reforms. Slightly less than half (47 percent) supported the prescription of substitution therapies in primary care settings and 62 percent were against eliminating the X-waiver required for prescribers of buprenorphine.

The National Academy concluded that there is “no scientific evidence that justifies withholding medications from OUD patients in any setting,” including in “office-based care setting[s].” It noted that “providers’ unwillingness to prescribe medications”—like for concerns about diversion or the “mistaken belief” that the medication is “just substituting one drug for another”—is a manifestation of stigma, and not of evidence.

“These findings suggest that policy changes alone are unlikely to lead to widespread availability of primary care–based medication treatment of OUD,” McGinty and colleagues wrote. “Longer-term solutions, such as incorporating addiction medicine into physician training, and delivery system reforms, such as embedding addiction medicine professionals in primary care practices, may be needed.”

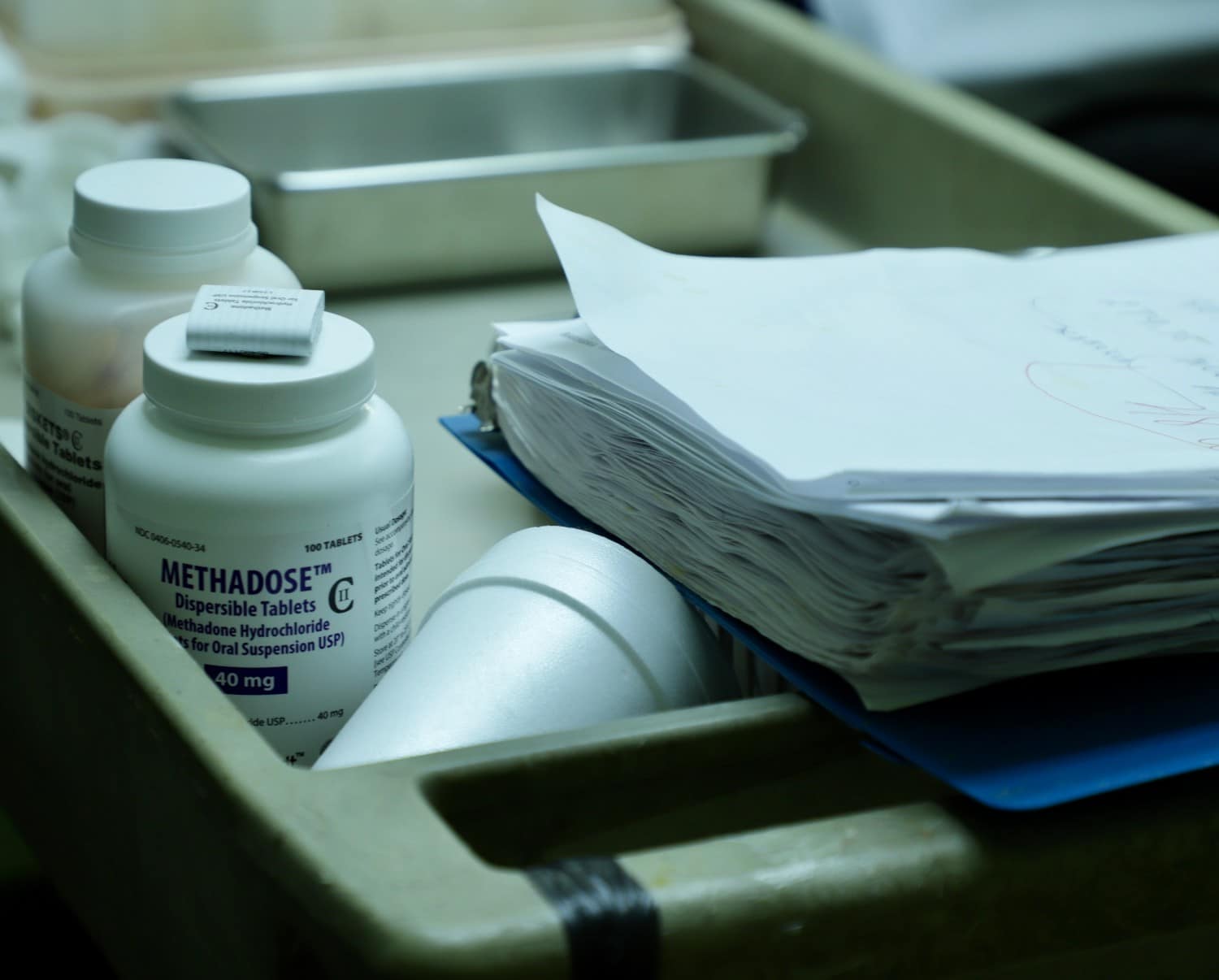

Photo of a methadone clinic by Helen Redmond

Show Comments