Before COVID-19, the District of Columbia was already experiencing a public health crisis that has only worsened since: overdose deaths. In 2019, the city’s toxic drug supply conspired with outdated, ineffective drug policy to cause what preliminary data estimate to be the second-deadliest year ever for people who use drugs in the District. DC’s overdose fatality rate surged 24 percent—in plainer terms, 260 more lives were needlessly lost to a preventable crisis.

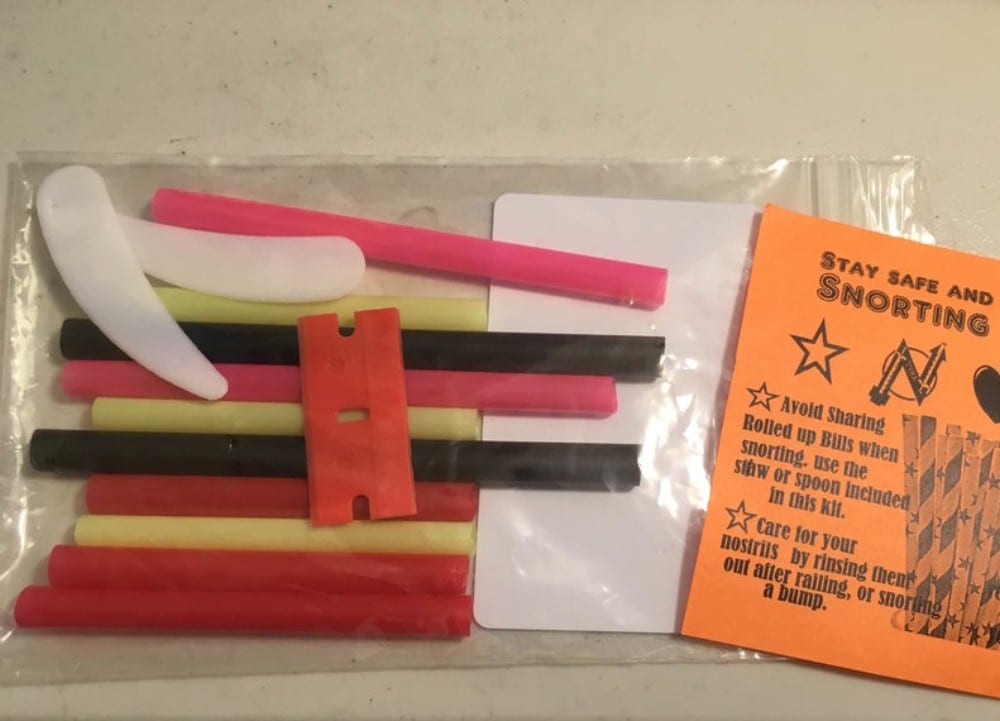

In May this year, the DC harm reduction hub HIPS and the Drug Policy Alliance* jointly submitted a letter to the DC Council, urging the removal of criminal penalties for the possession and distribution of so-called “drug paraphernalia.” DC law—specifically statute § 48–1103—stipulates that possession of materials flagged as being associated with drug use, including items such as safer snorting and smoking kits, is punishable by up to six months in prison and/or a $1,000 fine.

The statute also means that, in the middle of a global pandemic that has exacerbated the existing overdose crisis, HIPS and other service providers cannot distribute these essential, life-saving harm reduction tools to people who use drugs in the District.

Unsafe or shared supplies for snorting or smoking put people at risk of hepatitis C transmission, HIV, and both viral and bacterial infections. For example, rolled-up dollar bills, which are crawling with bacteria, remain one of the most common methods for snorting drugs.

Switching up your method of ingestion can help give your veins a break. The kits also offer an opportunity for service providers to connect with a new population.

In addition to preventing disease transmission and promoting hygienic practices, snorting and smoking kits can also offer people who use drugs an alternative to injecting. Because there are generally greater health risks associated with injection—skin and soft tissue infections, vein collapse, endocarditis, etc.—switching up your method of ingestion can help give your veins a break and reduce the risks. The kits also offer an opportunity for service providers, especially outreach workers, to connect with a new population of folks who don’t inject their drugs, but could still benefit from other harm reduction resources like naloxone, fentanyl test strips, drug/overdose prevention education and—when desired—substance use disorder treatment.

Since May, over 30 national and DC metro area-based organizations have added their signature of support for the policy revision that would enable such provision. The coalition has organized a petition to decriminalize safer snorting and smoking kits.

In nearby Baltimore, Harriet Smith, director of education at the Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition (BHRC), has witnessed the benefits of safer snorting or smoking kit distributions through client interactions. When BHRC started distributing safer snorting kits in 2019, Smith said, “People who felt invisible to needle exchange and other programs finally saw their experiences valued. Offering these supplies has allowed us to engage with our neighbors who are least likely to have consistent access to quality healthcare and most likely to experience overdose and/or be the first responder to an overdose.”

BHRC’s ability to distribute kits in Baltimore highlights how outdated the DC statute is. For years, harm reduction programs in other cities nationwide have legally distributed safer snorting and smoking kits, including the Chicago Recovery Alliance, the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance in Seattle, and San Francisco’s GLIDE and the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. In New York, the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center, Washington Heights CORNER Project and the New York Harm Reduction Educators all do so.

Despite legalizing cannabis for recreational use in 2015, DC has been slow to innovate when it comes to harm reduction. We witnessed this during the delayed expansion of naloxone access for people who use drugs and their loved ones—particularly Black Washingtonians, who made up four out of every five overdose fatalities from 2014-2018 (when fentanyl began devastating communities).

The criminalization of safer snorting and smoking kits is also a racial justice issue. From 2010 to 2016, 82 percent of people arrested on drug paraphernalia charges in DC were Black, when Black people comprise 46 percent of our population. This mirrors broader racial disparities in the District’s law enforcement practices: Overall, in the same time-frame, Black residents were arrested at 10 times the rate of white residents, typically for similarly minor reasons.

Criminalizing safer snorting and smoking kits has never made sense, but this is especially apparent during the pandemic.

Criminalizing safer snorting and smoking kits has never made sense, but this is especially apparent during a global pandemic from a virus transmitted through respiratory droplets, which are easily passed along when drug equipment is shared. We know that COVID-19 has amplified existing social inequalities. It’s no surprise that in a city with such grotesque racial disparities, COVID-19 would also be six times deadlier for Black residents than white.

Straws and stems are some of the most commonly shared drug use tools. We know this contributes to the spread of COVID-19, as well as other diseases. This historic moment demands that we break away from the status quo, and take common-sense steps toward improving public health, without leaving behind people who use drugs.

Other jurisdictions have taken such steps. The Canadian province of British Columbia, for example, expanded its safe supply program—an initiative originally developed in 2016 —to address the growing presence of fentanyl in the street drug supply. Through the MySafe program, British Columbians who use opioids are able to access prescribed hydromorphone via “vending” machines strategically placed in areas highly impacted by drug use or near safe consumption spaces.

It’s just one innovative, life-saving program among many that Canada has undertaken to address its overdose crisis, and highlights how archaic US drug policies are. We birthed the global “War on Drugs,” and amidst a global pandemic, massive social unrest, and pervasive, ever-escalating racialized state violence, our government has desperately clung to systems that we know were designed to fail us.

Harm reduction providers are essential workers; most have continued to operate since March, conducting syringe exchange and distributing naloxone in often-desperate attempts to stem the tide of fatal overdoses—which are estimated to have increased by 18 percent nationwide since the start of the pandemic.

Harm reduction organizations deserve much more than shoestring budgets, moralistic anti-science opposition, and a lack of recognition as healthcare providers on the frontlines of preventive public health. And at the bare minimum, we deserve not to have tools as simple and effective as smoking devices criminalized, piling more harm onto an already criminalized and at-risk population.

At the end of 2017, DC’s deadliest year ever for overdose fatalities, the Council unanimously voted to amend the Drug Paraphernalia Act of 1982 in an emergency measure to allow for the distribution and personal use of fentanyl test strips. The Council, especially Judiciary Chairman Charles Allen, should now act similarly and urgently in fully striking statute § 48–1103 and decriminalizing all drug paraphernalia.

It’s a small step towards addressing drug-user health, racialized criminalization and countless other injustices the drug war has inflicted—but it’s a necessary one.

* The Drug Policy Alliance has previously provided a restricted grant to The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, to support a Drug War Journalism Diversity Fellowship.

Photo of safer snorting kit via People’s Harm Reduction Alliance.