In 10 years, one in five people who inject opioids is predicted to die from a preventable heart infection, according to a simulation model developed by Boston Medical Center researchers. For some groups of people who inject, the infection is predicted to be far deadlier than overdose.

By 2030, approximately 257,800 injecting opioid users, or about 20 percent of the subpopulation, could die from endocarditis—an infection of the heart’s inner lining that has become one of the most common medical problems facing people who inject.

“As an infectious diseases physician, endocarditis is something that I see on a daily basis,” Dr. Joshua Barocas, one of the study’s authors and an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Medicine, told Filter. “Over the last 10 years, I’ve watched the number of hospital cases increase among young otherwise healthy people. Their only risk factor is injection drug use.”

The study authors behind the model projected mortality risks based off of behaviors like frequency of injection use and risky practices, like equipment sharing and skin hygiene.

Twenty-year-olds classified as “males” who inject once or more per day and practice risky injection techniques are at the greatest risk of dying from infective endocarditis, facing a more-than 53 percent chance of death by 2030. Those who inject less than once per day, even while practicing risky techniques, face a somewhat lower mortality probability of 44 percent. Decreasing injection frequency also reduces mortal risk for similarly positioned people classified as “females.”

“Until recently, injection-related infections were not as common as HIV, hepatitis C, and overdose. But then fentanyl hit the drug market. And polysubstance injection use became more common. Both of these lead to increased injection frequency,” said Barocas. “That, coupled with an inadequate supply of sterile injection equipment, increases the risk of bacterial infections like endocarditis. We’re seeing more people without access to sterile equipment who are injecting more frequently—a perfect storm for bacterial infections.”

Overdose tends to be seen by the public and politicians as the dire mortal health crisis facing people who inject opioids. As the study authors predict, almost one-third of the subpopulation overall face a 10-year mortality projection from overdose, compared to 20 percent for infective endocarditis.

But for specific vulnerable groups, the threat of death from the heart infection far surpasses that of overdose. Twenty-year-old “females” who infrequently inject but don’t use sterile injection techniques have an infective endocarditis mortality risk nine times greater than their fatal overdose risk. Such a trend is similarly seen in “males.”

“While overdoses are incredibly important for mortality, there are other complications of injection drug use that are treatable too. We can’t miss the forest for the trees,” Barocas said.

“Our results show that an individualized, patient-centered approach to the opioid epidemic that includes expansion of harm reduction services is needed,” write the authors. “Practically, this means meeting patients where they are and, perhaps, addressing injection technique first. Once a person changes their injection technique, the next thing to consider is injection frequency.”

The scale of life lost due to preventable infections is mind-boggling. The study authors calculated that people who inject drugs will lose more than seven million years of potential life to infective endocarditis over the next 10 years, assuming an average life expectancy of 75 years.

Much needs to change in order to save lives. “To stave off an even larger impending public health crisis,” they write, “multiple dimensions of the problem need to be addressed urgently: expansion of syringe service programs and other harm reduction efforts, improving initiation and retention on [medications for opioid use disorder], increasing research and development into new antimicrobials, and promoting system-level change that addresses the social and structural determinants of health.”

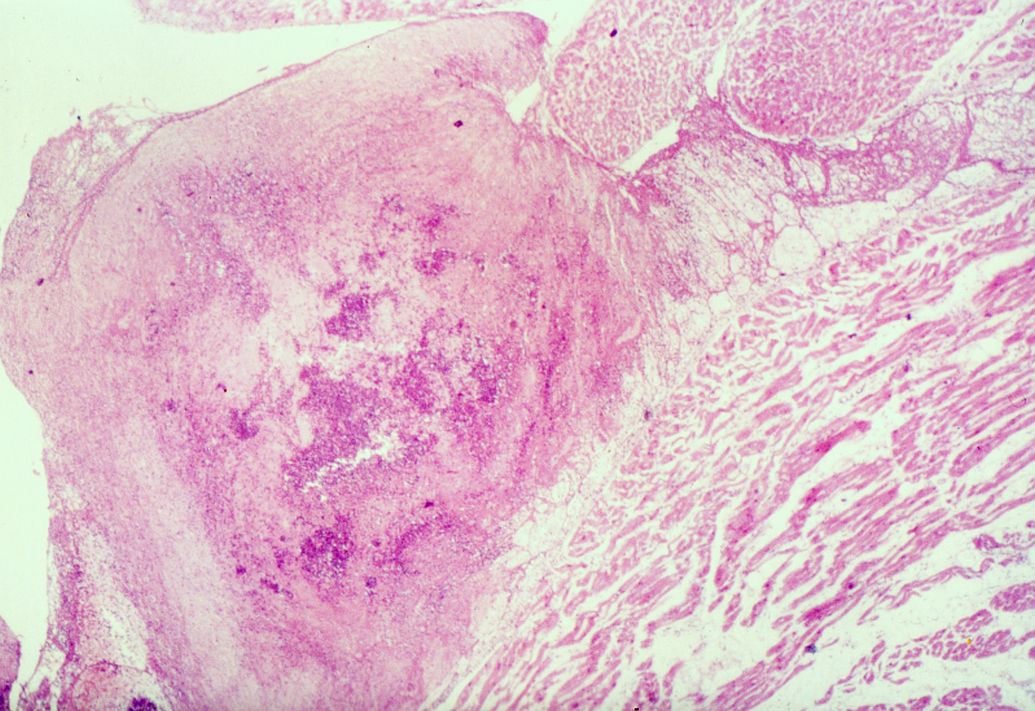

Image of endocarditis by Amadalvarez via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons

Show Comments