It’s dispiriting that in 2022, with decriminalization efforts taking off nationwide, adding more drugs to the Controlled Substances Act is still on the federal agenda. But the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has proposed placing five new psychedelic compounds in the key federal drug law’s most restrictive category, Schedule I.

The DEA released a proposed rule change on January 14 to put an impenetrable-looking group of substances—4-OH-DiPT, 5-MeO-AMT, 5-MeO-MiPT, 5-MeO-DET and DiPT—into Schedule I. That’s the category currently shared by drugs including heroin, LSD and marijuana. Under federal law, Schedule I drugs “[have] no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” They can’t be prescribed by a doctor, and any scientific research is subject to strict rules. And they’re heavily criminalized; distribution or manufacturing at least 10 grams of LSD, for example, is punishable by a 10-year mandatory minimum sentence, while simple possession can mean up to a year in prison.

A Schedule I classification would make it illegal to possess, distribute, buy, sell, manufacture or research these five drugs. None are technically illegal as things stand, and they are actually sold by some manufacturers for scientific purposes. The DEA is accepting written and oral feedback on its proposed rule change until February 14.

“They are definitely being used intentionally and not substituted for other tryptamines.”

But what exactly are these substances? If the names look like alphabet soup to you, you’re not alone. They’re not as well known as LSD or psilocybin, but they may share similar effects. The famous chemist team Alexander and Ann Shulgin studied these and hundreds of other compounds at length, testing them on themselves and documenting the effects they felt. In response, the DEA raided their lab in 1994.

“[They] are definitely being used intentionally and not substituted for other tryptamines,” Mohawke Greene told Filter, referring to a chemical class of drugs that includes LSD and psilocybin.

As the former director of New York DanceSafe and in their current work, Greene works with drug users to encourage safer practices in nightlife and club settings. “[These] substances hardly even pose a threat at all. The DEA just hates people who use drugs.”

Yarelix Estrada, the director of New York City Psychedelic Society, said that she’s not familiar with these specific drugs but has used other “research chemicals” in the past. She described a subset of psychedelic user who may start with drugs like LSD or psilocybin but goes on to seek out any number of research chemicals—which, despite that term, have been little researched.

“[It’s] people who self-identify as ‘psychonauts’ who have probably done a fair amount of exploring with traditional psychedelics, and then want to find other tryptamines to explore,” she told Filter.

Estrada explained that many of these drugs can often be purchased online in quantities as small as a gram, paid for with PayPal or cryptocurrency, and shipped to your home.

The DEA claims these drugs have a high risk of “abuse.” It cites one confirmed death in 2004 that involved 5-MeO-AMT together with alcohol and an antidepressant, admitting, “it is unclear what role 5-MeO-AMT played in the death.” The agency also vaguely references emergency room admissions related to 5-MeO-AMT and 5-MeO-MiPT.

The National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) has documented at least 487 lab reports involving these drugs in the last 20 years, throughout the US. That’s a drop in the ocean compared to the thousands of lab reports just in 2020 for drugs like LSD, MDMA or psilocybin.

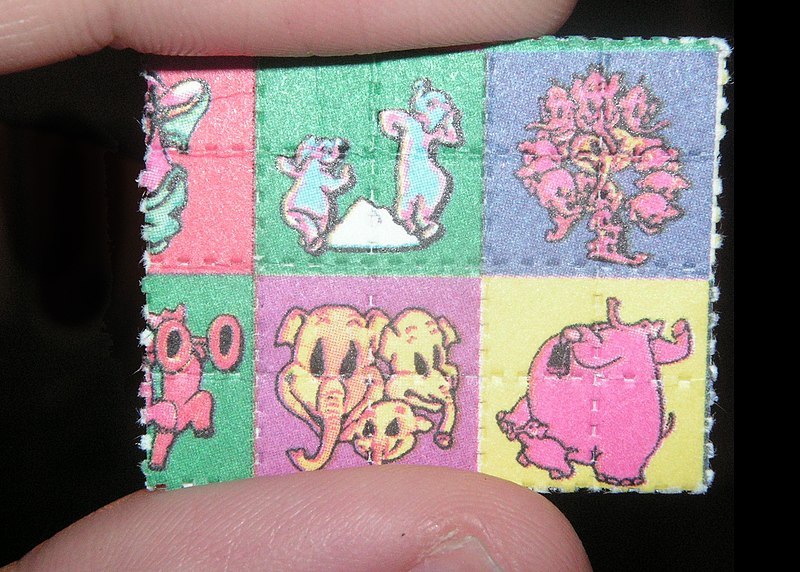

The DEA and NFLIS claim that the five drugs in question appear in powder, tablet, capsule, liquid or blotter-paper form–and also, sugar cubes. Claiming that people often purchase them in-person as well as online, they add that the drugs may be falsely sold as LSD due to their similar effects.

There’s no question psychedelic drugs like MDMA or LSD can be adulterated, putting people at risk. But there’s little evidence that these five drugs are misrepresented as the DEA claims.

The DEA admits, “there is no evidence of significant diversion” from legal suppliers.

“From my experience in drug checking, I haven’t seen situations where these particular substances have been sold instead of the drugs people have asked for,” Estrada said. However, “It’s really hard to say because we don’t have the technology to know what any adulterants are.”

Simple drug checking tools, like reagent kits, won’t tell you if you have one of these tryptamines. And even if you’re lucky enough to get your hands on advanced FTIR technology to analyze your drugs, it only reliably tests powder-based drugs—not liquids or other forms.

The DEA identified 31 suppliers in the US who legally sell these drugs. But it admits, “there is no evidence of significant diversion”—or selling to the illicit market—from these suppliers. So why the reaction?

Each of these drugs is chemically similar to other drugs already in Schedule I. Because of that, even without the DEA’s action, the drugs could still be subject to the Federal Analogues Act, which allows prosecutors to criminally charge people who possess or sell analogues.

But that law has been challenged legally, and cases are hard for prosecutors to win. The DEA’s scheduling would make it far easier to lock people up for these drugs.

In summary, we have one death nearly 20 years ago that may be linked to one of these drugs, and a small number of legal suppliers that aren’t selling them to the illicit market. It’s a poor pretext to throw the full weight of federal drug law against these substances—and the Black, Brown and poor defendants who would inevitably be targeted.

Photograph of blotter art by Psychonaught via Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

Show Comments