Colorado legislators have proposed a working group to study the use of colorimetric drug tests within the criminal-legal system, and identify less-harmful alternatives. The group would analyze both court proceedings as well as internal disciplinary processes of prisons and jails, where the tests have a profound impact on day-to-day life.

The bill narrowly passed the House Judiciary Committee on February 26—with an amendment for the working group to include at least one person impacted by a colorimetric false positive—and is now being reviewed by the Appropriations Committee. It appears to be the only such proposal in the current legislative session, in any state.

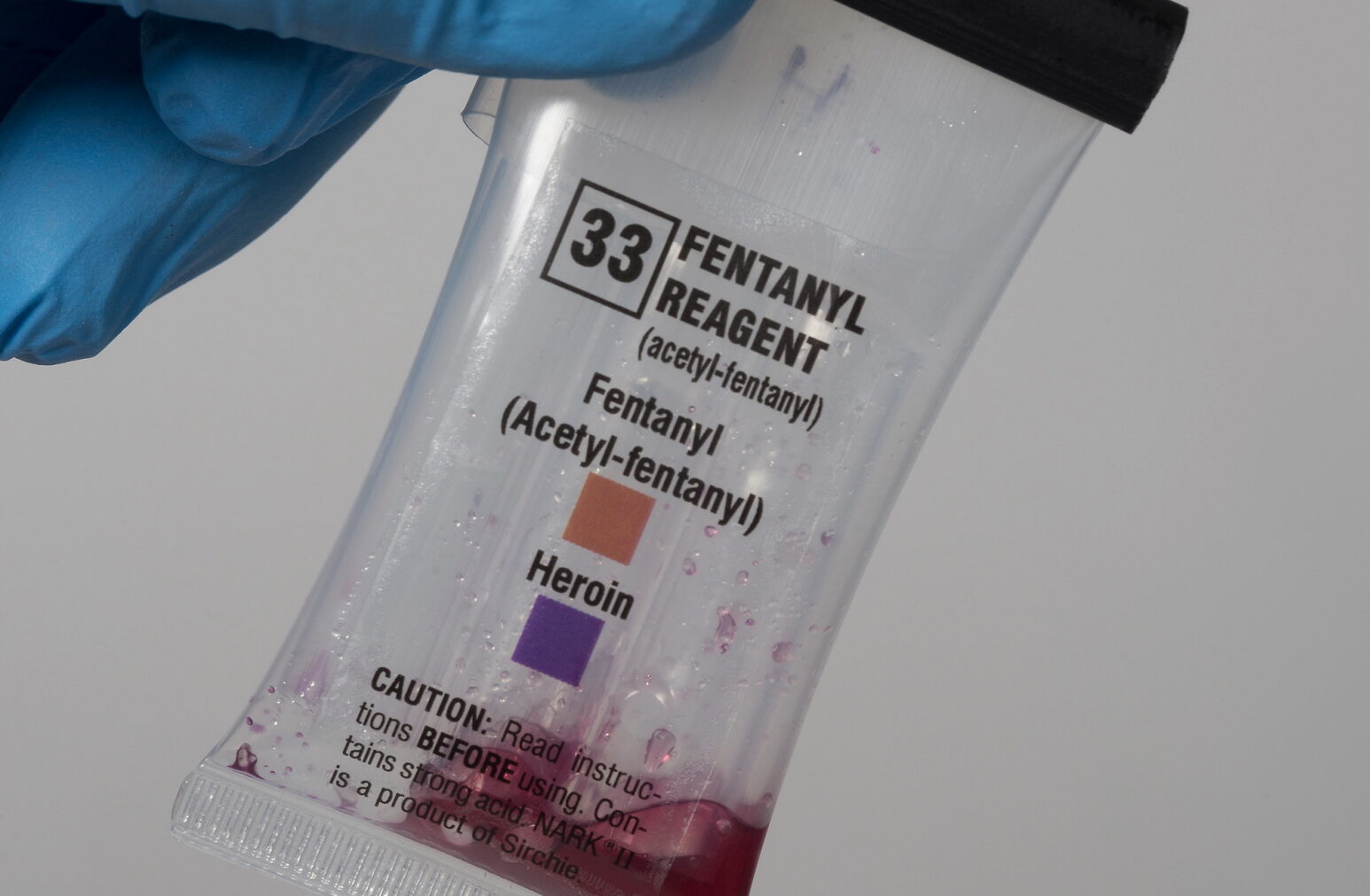

Colorimetric drug tests, AKA presumptive tests or field tests, are on-the-spot chemical reagent tests widely favored by law enforcement and in correctional settings. Unlike urinalysis or other methods that check bodily fluids, these are used to check suspected drug samples, like pieces of paper. They are notoriously inaccurate, and per manufacturer instructions are supposed to be confirmed with laboratory testing, not used as evidence on their own.

As a 2018 National Institute of Justice report put it, forensics equipment approaches a sample suspected of being e.g. cocaine and asks, What is this substance? While a colorimetric test asks, Is this substance likely cocaine?

The Colorado bill heavily cites a landmark 2023 analysis of national drug arrest data, which concluded that these tests are “one of the largest, if not the largest, known contributing factor to wrongful arrests and convictions in the United States.”

Though public health drug-checking has been gradually getting traction as a harm reduction tool, the vast majority of the forensics field is contracting with law enforcement. Colorimetric tests are involved in an estimated 770,000 arrests each year, but to get someone convicted a prosecutor will use confirmatory results from a lab; field test results alone aren’t going to hold up in court. Which is why the harms of these tests happen outside of court—in extrajudicial processes like plea bargains and prison disciplinary sanctions.

An estimated 30,000 people are wrongfully arrested each year based on colorimetric tests results. Some of those who can’t afford bail will sit in county jail, waiting on confirmatory testing from backed-up crime labs, until they eventually end up pleading guilty. You only need confirmatory test results if you’re going to trial, to prove the field test result was a false positive; if you’re taking a plea deal, no one cares if the test was wrong.

The Colorado working group seems likely to cover the ways colorimetric tests put people in prison, but would hopefully also cover the ways they also keep people in prison for longer, often with substantially worse living conditions in which to pass the extra time.

“Colorimetric field drug tests are also used in a variety of other settings in Colorado, including correctional systems, possibly resulting in unfair disciplinary sanctions,” the bill states. “The extent of use in these settings is unknown.”

There’s a wide range of high- and low-tech drug-checking equipment out there, but colorimetric tests are the overwhelming favorite among law enforcement and corrections officers. They’re quick, inexpensive and require no special training to use.

Compounding the already extremely high likelihood of false positives is that the drug supply in prisons and jails is very different compared to the free world. Some facilities have a market for fentanyl and some don’t, but opioids are rarely if ever the mainstay. These days that’s usually synthetic cannabinoids, which are pretty much the least likely class of drug to be correctly identified with a colorimetric test.

In prisons, after a positive result from a colorimetric test it’s common for the person accused to be confined to their cell until an investigation is completed—which can take months. They can lose their work assignments, visitation privileges and personal property including legal documents. They can lose the “good time” they’d shaved off their sentence, or their shot at parole or other forms of early release.

People in custody of the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, for example, have the right to confirm the results of urinalysis testing, but not colorimetric tests of their mail. The department “generally doesn’t obtain or allow” people facing disciplinary hearings to use confirmatory testing.

Between January 2022 and March 2024, the New York City Department of Correction (NYCDOC) bureau that handles field testing recorded that of the incoming mail samples tested for fentanyl, 89 percent tested positive. The percentage is that high because it only reflects mail that looked suspicious enough to be tested for fentanyl in the first place, not all incoming mail. That statistic became the basis for NYCDOC’s claim that the most common way fentanyl entered the jail system was by mail.

A similar progression of events is unfolding at prisons and jails across the country. Confirmatory testing of the two brands of field tests used by NYCDOC later showed they had false positive rates of 79 percent and 91 percent.

In December 2023 Filter reported that the Washington State Department of Corrections was still using presumptive colorimetric test results to sanction people in custody even while facing a class-action lawsuit filed over the practice. The person at the center of that article was later transferred to a different prison based solely on a false positive.

He was ultimately able to use Filter‘s reporting to win his appeal and get transferred back, but only after spending eight months at a more violent facility on the other side of the state, hours away from his family. During that time the department banned all greeting cards and similar mail; Filter reported that use of those same colorimetric tests was the basis of the new policy.

Most contraband drugs find their way into prisons and jails via staff, visitors or the United States Postal Service. Corrections departments will tell you it’s mostly USPS, and to a lesser extent visitors. Staff are encouraged to liberally field-test incoming mail, because this is what creates the robust body of evidence currently driving all the correctional mail bans, which is convenient for the private contractors with monopolies on the mail-scanning services that take over.

Contraband drugs do enter jails and prisons by mail. It’s also true that visitors bring them in. But broadly speaking, the most common way drugs enter a correctional facility is that staff bring them in. Fewer colorimetric tests are expended on this.

Top image and second inset graphic via State of New York Offices of the Inspector General. First inset graphic via National Institute of Justice.