In early June, São Paulo Mayor Ricardo Nunes signed an agreement with the researchers behind Calixcoca, a “cocaine vaccine” in development since 2015. A team at the Federal University of Minas Gerais had previously used public funding to demonstrate the vaccine’s safety and efficacy in rats. Now, with over $800,000 USD from São Paulo, it’s expected to advance to human trials.

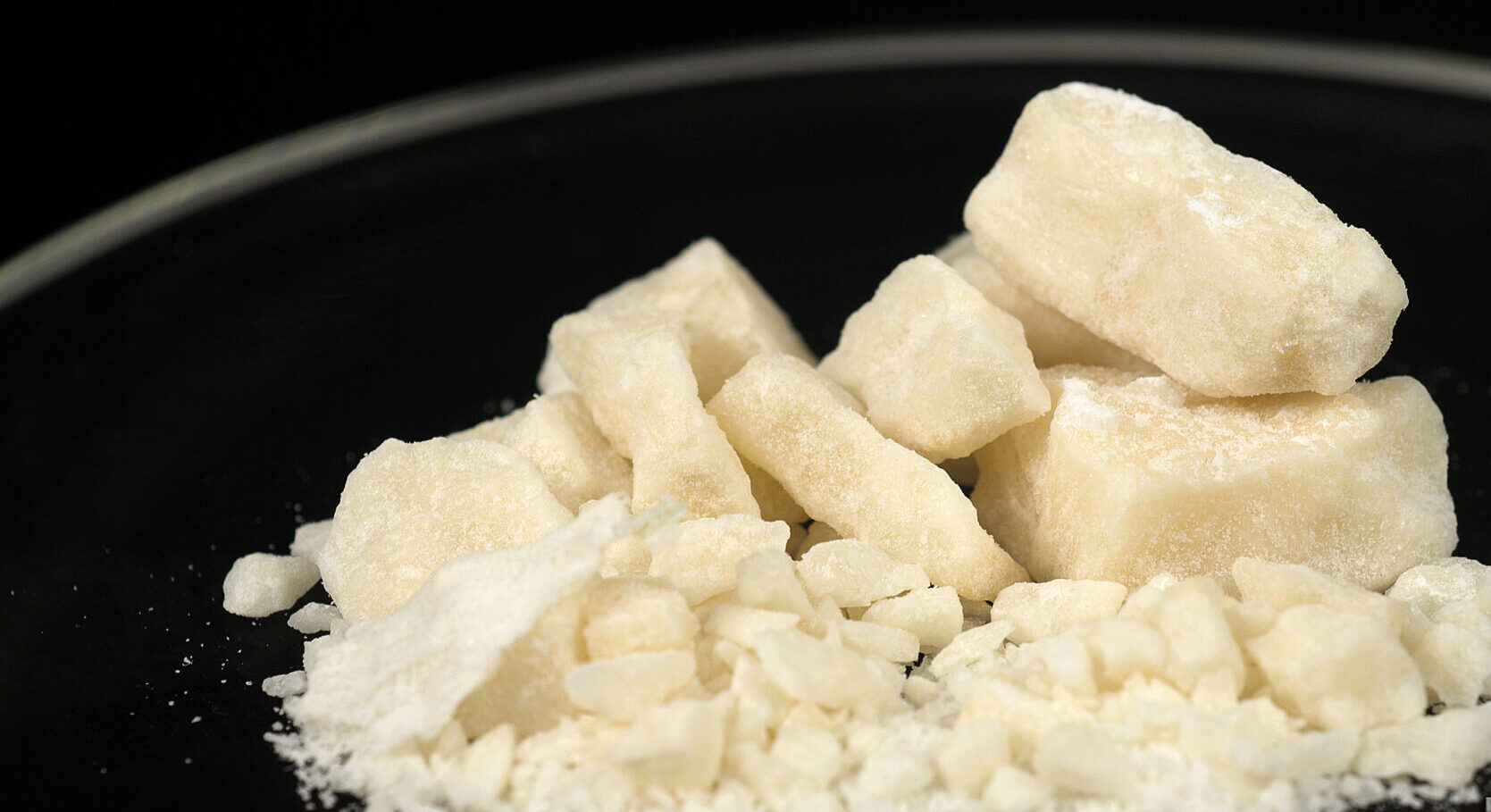

Calixcoca is not intended to reverse cocaine overamps. Like other so-called vaccines for illicit drugs, it proposes to block euphoric or other psychoactive effects. If approved for humans, it would target cocaine in the bloodstream with antibodies that bind to it and prevent its absorption. In addition to crack cocaine, researchers have suggested an applicability for other illicit drugs. There is not yet a timeline for the proposed human trials.

There has been much fanfare about Calixcoca being a finalist for the Euro Innovation in Health award. But officials don’t appear be similarly interested in any harm reduction-minded questions about how the vaccine would work in the real world. How long it would be intended to last; how it might be affected by the consumption of other substances alongside cocaine; how the scale of harms it proposes to protect against measures up to the harms it has the potential to cause.

It’s hard to imagine the vaccine not being used in close connection with law enforcement.

One particular area of concern is that being “immunized” to cocaine’s effects might push some people to use larger and larger quantities in order to feel those effects—and as a result increase their risk of criminalization, which may already have been very high, and their risk of fatal overamps, which was likely very low.

This agreement comes just as the city opens a new investigation into a disproven “crack epidemic.” The ethical concerns of bringing such a vaccine to market, especially with this level of investment from São Paulo, are substantial. We could see judges offer such a vaccine as an alternative to prison time. One way or another, it’s hard to imagine it not being used in close connection with law enforcement.

It’s very easy, on the other hand, to imagine that the people being vaccinated would not all be vaccinated voluntarily.

One of the most dangerous things about the therapeutic communities is that no one oversees them.

Calixcoca would be aimed at people in recovery, with the intent of preventing recurrence of use. This is especially concerning in the context of Brazil’s continued support of therapeutic communities, religious institutions notorious for their “treatment” of patients who are often taken to them against their will.

Brazil’s stance is that drug use must be addressed with treatment, whether or not that treatment is voluntary. This has been used in service of forced sterilization of pregnant drug users, and a pattern of therapeutic communities using physical and psychological violence against drug users and other vulnerable groups in their “care.” Like carceral psychiatric institutions in the United States and elsewhere, they forcibly sedate patients as a form of control and punishment, including teenagers who try to escape.

One of the most dangerous things about the therapeutic communities is that no one oversees them. Despite their practices being denounced as human rights violations, again and again, they continue to enjoy government favor and funding even while they have total discretion as to how they enforce abstinence and their religious ideology around “cleanliness.”

Brazil’s obsession with crack cocaine and the people who use it is not about saving lives. Illicit drug vaccines in general are not about saving lives. This is another way of pathologizing poverty, and ignoring the systemic failures of the country’s health care and social support systems in favor of punishing the individuals already suffering the consequences.

Photograph of crack cocaine via United States Drug Enforcement Administration

Show Comments