The true measure of how a prison treats its prisoners can be found in their tattoos. Hands clasped in prayer; hands gripping bars; open coffins; scripture verses. Only God can judge me; or its variant, No man can judge me.

People who haven’t been impacted by incarceration often assume that tattoos inked in prison signify whatever the person did to end up there. In reality, most prison tattoos are not about “crime”—they’re about what comes after being convicted.

Teardrop tattoos are broadly associated with gang-related murder, but can also carry the alternative meaning that the person was raped by another prisoner. While a cobweb tattoo on an elbow can signify a racially motivated murder, cobwebs elsewhere on the body often symbolize the feeling of being trapped.

Prison tattoos are an evolving form of protest art, critiquing the injustices of the criminal-legal system and empowering the silenced through creative expression. Microphone tattoos can represent the feeling of having no voice in a carceral setting; alternatively, they can appear on prisoners who have gained power and influence—”holding the mic”—within that setting.

Even the process of tattooing itself is an act of resistance—tattooing is illegal for prisoners, and any equipment associated with it is contraband.

For veteran artists like JonJon, 41, tattooing is a lifeline within the critically underresourced Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) system. Customers pay him in commissary goods, cigarettes, stamps or whatever they have access to.

“Tattooing is how I’ve survived roughly 20 years in prison,” JonJon told Filter. “It’s all I know, and it’s how I eat.”

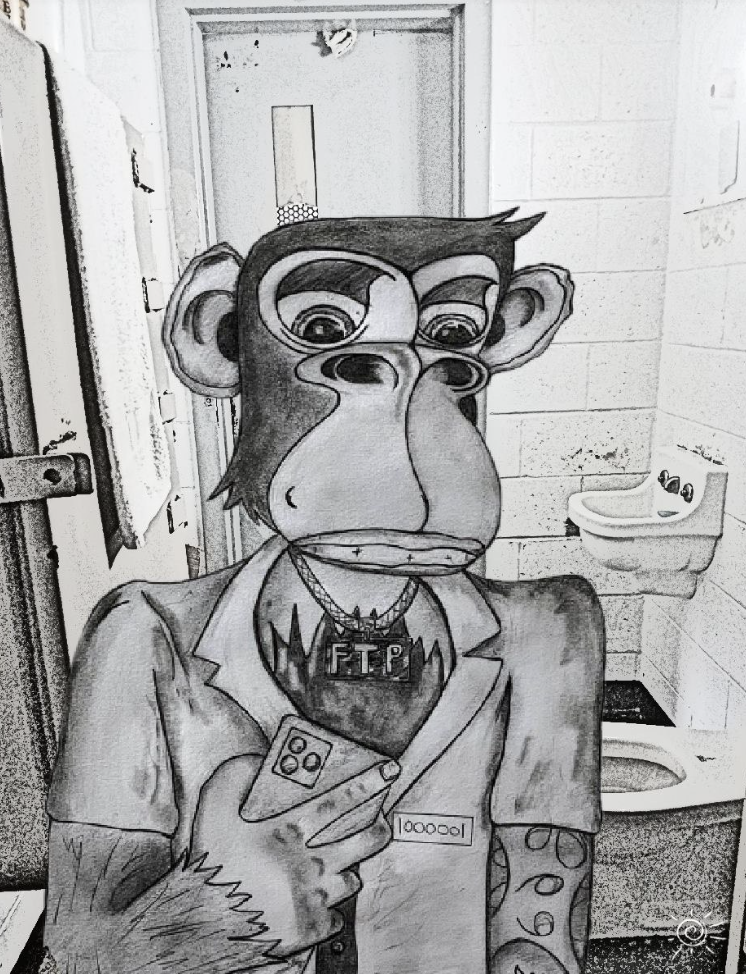

In GDC facilities, a common tattoo is the “hanging man”—a symbol of being sacrificed on the “tough-on-crime” alter, by way of excessive sentencing. Another is the “13 & ½”—12 jurors, one judge, a half-ass chance. Monkeys dressed in prison-issue uniforms have a few different meanings, all of which are fairly self-explanatory.

Artist sketch: Caged monkey trying to lead the semblance of a normal life, in an abnormal environment

Artist sketch: Caged monkey trying to lead the semblance of a normal life, in an abnormal environment

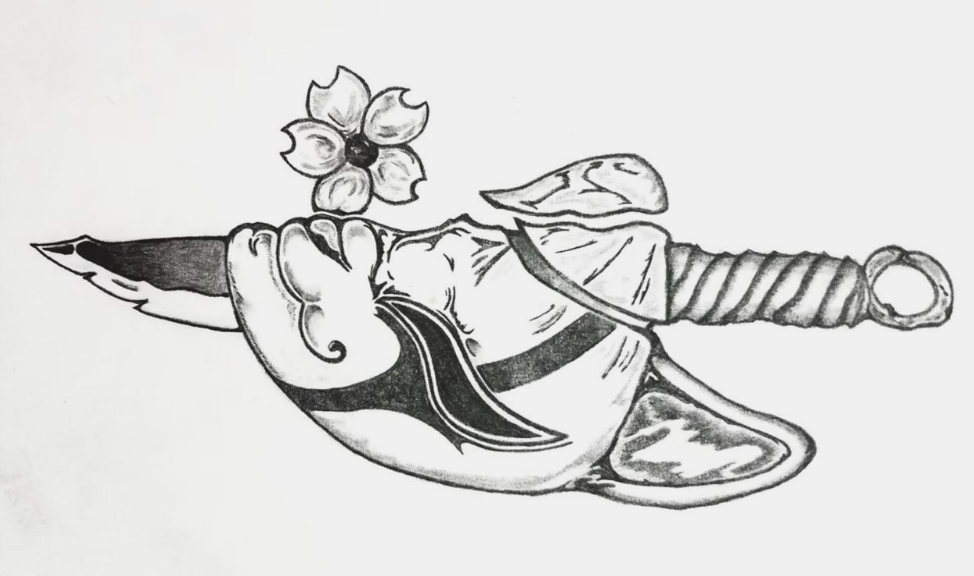

Artist sketch: “Trying to find the beauty in our death,” referring to incarceration

Artist sketch: “Trying to find the beauty in our death,” referring to incarceration

“During the AIDS epidemic of the ’90s, when we were first coming in, there were all these old men that had this tattooed chain thing,” JohnBoy, 58, told Filter. “A cross formed using a pickaxe and a shovel, with a ball and chain at the bottom of it. ‘Chain gang’, right? So if you had that tattoo, it didn’t say you’d been in prison—but you only got that in prison.”

Another design popular in that era was the outline of the state of Georgia, with bars and handcuffs linked through. “A ‘fuck you’ to the state, and its history as a prison [labor] force,” JohnBoy said.

JohnBoy has been an intermittent tattoo artist over the course of his 30-plus years in GDC facilities. On one man, he inked a planet surrounded by rings and stars, bearing a jagged crack representing the daughter who died the same day he was arrested. Another man got a list of everything he’d been before he was sent to prison—Marine, dad, husband, coach—on his chest, in the same place his ID card was when clipped to his shirt. He told JohnBoy that he wanted the tattoo to help him not forget who he was—but also so that if he died in prison, his body would bear the record, too.

“It’s like, ‘Look at my mutilated skin! I am known by people! I matter to the people who matter to me!’”

“My first prison tats were in opposition to the things ‘normal’ people did,” JohnBoy said. “They were a way I showed that I was more than my crime and that I had a point of view, too. That’s incredibly important when you’re staring down the barrel of a life sentence, and you’re now effectively a person with no legal or political voice.”

Like in the free world, tattoos bearing the names or birthdates of loved ones are common. But in prison, these are often inked mournfully, to commemorate what someone couldn’t be there for—funerals of parents; births of grandchildren. Often these tattoos take the place of holiday or birthdays gifts that prisoners are unable to get for their loved ones.

“Rows of tombstones with RIP and lists of next of kin are the tangible evidence of our existence in the world,” JohnBoy said. “It’s like, ‘Look at my mutilated skin! I am known by people! I matter to the people who matter to me!’”

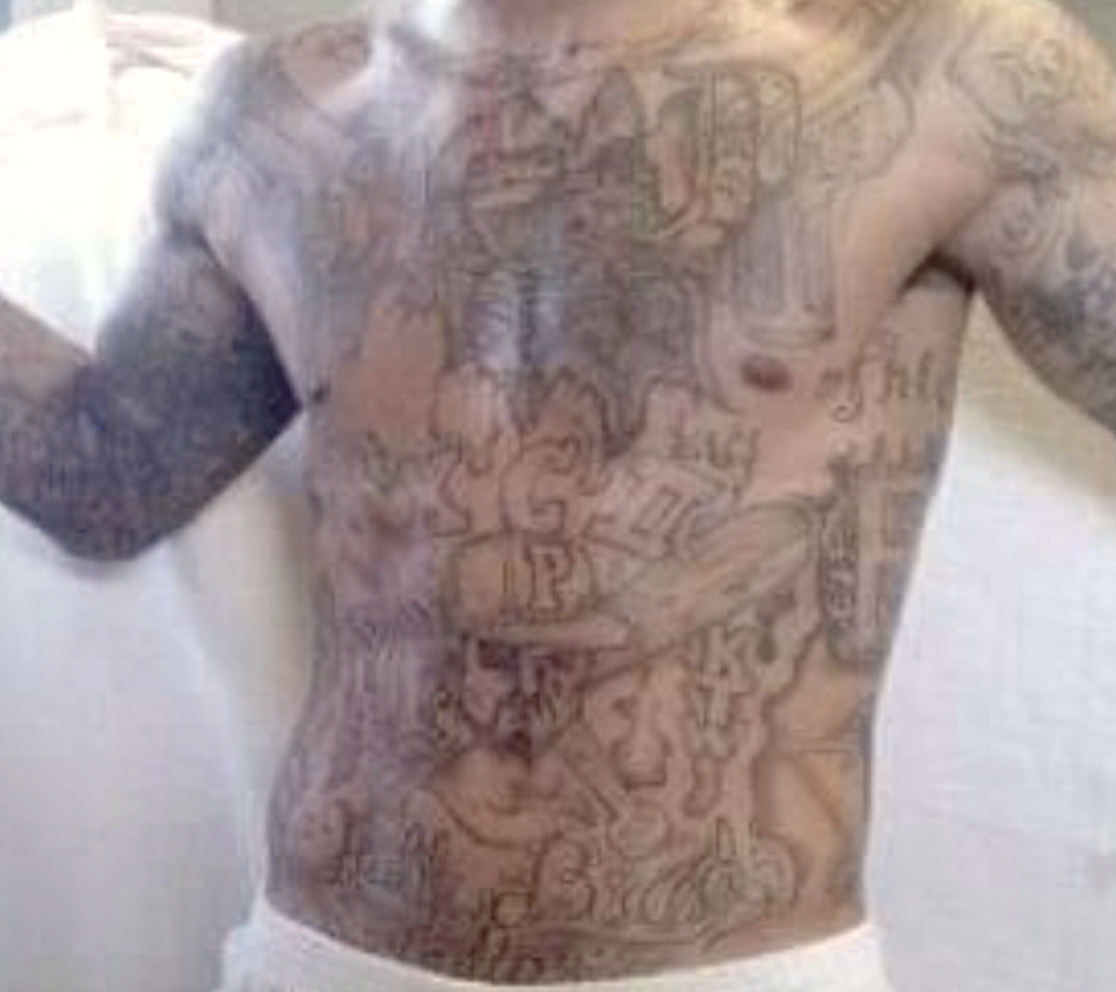

A tableau showing one man’s journey from gang member to prison minister

A tableau showing one man’s journey from gang member to prison minister

The skull of a different prisoner being suffocated by two snakes—”Justice” and “Law”

The skull of a different prisoner being suffocated by two snakes—”Justice” and “Law”

“If you’re a tattoo artist here, you meet all kinds but you’re … common ground for everybody,” AG, 41, told Filter. “Neutral territory. Nobody fucks with the tattoo man.”

A long-time artist who, like JohnBoy, is serving a life sentence, AG was first incarcerated in a county jail more than a decade ago. “Modern” tattoo guns weren’t available, and all tattoos were done via “pick-poke”—ink on a staple, paperclip, sewing needle, old piece of wire or whatever else was handy.

“They were rude and crude,” AG recalled. These tattoos don’t age all that gracefully, at least compared to what he began seeing after he was sent to the GDC prison system. “Guys were making tattoo guns using motors out of electric razors, CD players … any kind of small motor would make it work. And really that’s evolved, because today we have the water guns.”

Running the water from a sink across a DIY tattoo gun provides power that moves the needle. Highly effective, depending on your water pressure.

Sky without fences

Sky without fences

Self-portrait, JonJon

Self-portrait, JonJon

But even as AG has seen some prison technologies advance, he’s seen others degrade. “We used to have more regular access to real tattoo ink, as it used to be a regular staple on the black market,” AG said. “But guys make more money prioritizing other things to come in.”

Ink these days is either baby oil or vaseline. Pour into a shoe polish can with a wick added so it burns off like a candle; catch the soot; mix with some water—and you have ink. Not sterile, but serviceable.

In 2022, a Minnesota prison began a pilot program to mitigate transmission of HIV and hepatitis C via tattoo needles. Prisoners reached by Filter were in broad consensus that a tattoo harm reduction program would be welcome in GDC, and desperately needed. It’s unclear how many of the system’s nearly 50,000 prisoners have untreated hep C—GDC conducts minimal testing, and does not track transmission.

“A lot of people say, ‘Well, I’ve never heard of people getting tattoos like that on the street,’” AG said. “Well, of course not. The reason why it happens here is because there’s so little left. So little to live for, and you have to live up to something.”

All names have been changed at sources’ request.

Top image courtesy of JohnBoy. Inset self-portrait courtesy of JonJon. All other images courtesy of Anonymous.