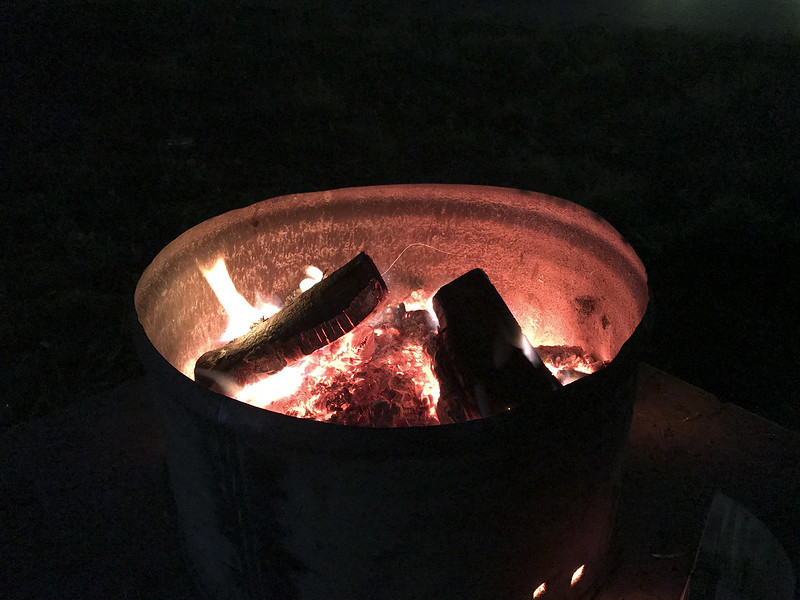

The city of Winnipeg, Manitoba is giving free steel fire barrels to unhoused residents living outdoors. Officials say it’s to prevent injuries or deaths from fires used to stay warm. They will distribute 15 200-liter barrels through community partners, and collect them again in the spring. Homelessness advocates point out that the measure is nowhere near adequate for people’s needs.

The Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service (WFPS) responded to 181 fires at encampments for unhoused people in 2021. Most, as the service acknowledged, were minor. But one explosion caused a person’s death.

“It’s important for us to limit that as much as possible,” WFPS Assistant Chief Scott Wilkinson told Filter. “One of the things we do is educate about where things should be placed, how to manage heating and fuel usage and fires at the encampments, and we have our staff circulating within that group. However we still have ongoing issues with potential fire spread from these open fires.”

Temperatures in Winnipeg have been hitting an average daily low of -1° Fahrenheit in January.

Wilkinson confirmed that the barrels are intended only for outdoor use and for warming, saying that they should not be used for cooking, and should burn clean, dry wood and not garbage.

“The only real issue we approach with regards to having to vacate an encampment is if there are persistent fire safety violations that may result in injury or death,” he said. “If we continue to advise on some significant fire safety concerns with heating use or fires that are too adjacent to or involving potential spread to or within the shelters, we will eventually look to vacate those for the safety of the resident and the adjoining residents.”

The barrels are not a real solution for anyone, said Marion Willis, executive director of the local homelessness service agency St. Boniface Street Links. She emphasized that the city needs to do a better job of coordinating services for unhoused residents, with the goal of meeting all their survival needs and getting them into permanent housing.

“People who are looking for warmth are actually looking for warmth inside their encampment,” she told Filter. “A burning barrel is not going to help them be warm … they’re still going to use propane heaters and whatever else they can.” That will put people at continued risk of explosions and fires, she said.

The city’s response to encampments has gone back and forth in recent years, creating much controversy.

According to a survey released in November by End Homelessness Winnipeg, over 1,100 were counted experiencing homelessness in Manitoba’s capital on one night in April. This included 370 completely unsheltered people and 54 in encampments.

The city’s response to encampments has gone back and forth in recent years, creating much controversy. In 2019, it began plans to hire a contractor to remove encampments in city parks and along the river. But in response to significant opposition, the city canceled the plan, and in June 2019 it implemented a new policy.

Calls to 311 or 911 reporting encampments are routed to an outreach organization, Main Street Project, which sends service workers who try to connect unhoused residents with support. Police do not attend in most circumstances, but are sent if there is deemed to be a serious safety risk.

But then in June 2020, the city announced plans to remove two encampments along the Disraeli Freeway. And in October 2021, it implemented a ban on encampments under bridges, also prohibiting open fires.

In January 2021, with shelters reducing capacity to comply with COVID-19 social distancing requirements, some unhoused residents were turned away from shelters in freezing weather because of a lack of bed space. In November 2021, the Manitoba provincial government granted $1.5 million to build a new “warming space” with 150 beds for unhoused people.

Kristiana Clemens, manager of communications and community relations for End Homelessness Winnipeg, said that there are currently 681 shelter units in the whole city—and that these spaces are actually not occupied to capacity.

“At the same time we’ve added these hundreds of emergency overnight beds, we’ve lost hundreds more low-income housing units.”

“Now we’re in a situation, midway through the winter, where certainly the adult and youth spaces are very busy, but we don’t have evidence of those spaces going over capacity, overall,” she told Filter. “There are still going to be people who don’t want to go to an emergency shelter or safe space because they do not feel comfortable accessing a congregate setting.”

She explained that people may decline shelter services because of disabilities for which they don’t receive care, past trauma from experiences in shelters, or having previously faced evictions or restrictions on couples, pets or belongings.

“Putting people in a shelter is not housing them,” she added. “At the same time we’ve added these hundreds of emergency overnight beds in recent years, we’ve lost hundreds more low-income housing units.”

She stated that the province of Manitoba needs at least 23,000 new housing units of housing to meet the national average of housing per capita. Manitoba has nearly 5,000 people on a waitlist for social and affordable housing, but only 60 available units.

Photograph by Billie Grace Ward via Flickr/Creative Commons 2.0.

Show Comments