Washington State Department of Corrections (WDOC) staff are now permitted to carry Narcan while on duty. Though the change is not reflected in WDOC’s emergency medical treatment policy, some corrections officers (COs) have been carrying the opioid overdose antidote since at least September. Narcan is still not available to prisoners, who are vastly better-positioned to respond to overdose than COs.

WDOC did not answer Filter‘s inquiry about when staff were authorized to carry Narcan on their person. It’s likely the change was implemented August 31, the date many internal updates have traditionally come into effect. It may also have been facilitated by the Food and Drug Administration’s recent approval of over-the-counter Narcan products, without requiring a prescription.

All WDOC prisons have had multiple Narcan kits on premises since 2018, but in locations so secure that even staff couldn’t access them. In April, Filter reported that many COs at Washington Corrections Center (WCC) were unable to locate the kits, and some were unwilling to use them. Despite required trainings, a number of COs did not know how to properly use Narcan and mutually discouraged each other from learning.

“You should have access to it,” CO Rory McCracken told me, referring to WCC prisoners including myself. “You guys are in a better position to save a life with Narcan—you’re there all the time.”

McCracken has carried Narcan on duty since early September. He told Filter that to the best of his knowledge, there was no announcement to staff; one day he came in to find a lieutenant passing out kits during shift change. Those who wanted them just had to sign a form and watch a 10-minute training video.

Prisoners, he noted, could just as easily watch that same training alongside the orientation video all of us are required to watch when we first arrive. At the very least, one of the Narcan boxes could be kept in the dayroom for prisoners to access when someone overdoses.

WDOC did not respond to Filter’s inquiry about whether Narcan was authorized as PPE because staff intended to use it on themselves.

WDOC Media Relations Manager Tobby Hatley said the department began discussing the change in 2022, when a CO suggested allowing Washington State Penitentiary staff to carry Narcan as part of their Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). This was kicked up to Washington’s Statewide Security Advisory Committee—the same process by which the Narcan boxes were introduced in 2018—and resulted in WDOC authorizing all employees and contract staff to carry a personal supply of Narcan while on duty.

“Several facilities began ordering Narcan and issuing it to staff,” Hatley told Filter. “Some facilities have begun adding Narcan to their Automated External Defibrillator stations as an alternative to issuing it to staff.”

Hatley did not respond to Filter‘s inquiries about which facilities were taking which approach; whether staff responding to overdose were required to administer Narcan; or whether Narcan was authorized as PPE for the purpose of staff using it on themselves, after perceived exposure to fentanyl.

Some WCC staff claimed that cops out on the street carry Narcan to use on themselves or their partner if exposed to fentanyl during pat searches. Prison cops conduct way more pat searches than outside cops, they reason, so they definitely need a personal supply of Narcan just in case.

Secondhand fentanyl exposure is a myth; it physically cannot cause an overdose. If you’re conscious enough to Narcan yourself, you’re not experiencing an overdose either.

Many staff have no intention of requesting the kits in the first place. Four COs expressed a moral objection to carrying Narcan, citing the debunked myth that naloxone access enables drug use.

Another CO told Filter that he requested a kit but was told the facility had run out. A different WCC staff member subsequently told Filter that Narcan is still available upon request, the information just hasn’t been circulated very well.

COs responding to an overdose often show up without Narcan, and have to double back to go find some. But even if they carried it on their person, they’d still be minutes slower than the prisoners who were at the scene the whole time.

“At Stafford Creek it would take a while for them to show up,” a WCC prisoner told Filter, describing various overdoses witnessed inside various WDOC facilities. “It’s a big place. If the cop on scene says it’s an OD on the radio, then the next guys who show up might stop and get [Narcan] before they come—but only if he says it’s an OD.”

Nathan Lewis, also currently incarcerated at WCC, was present at two overdoses inside Coyote Ridge Corrections Center in 2022—one of them fatal. “The cops had to come and get him, and then they [had to leave and] get the first aid kit,” Lewis told Filter. “It takes forever.”

“Here, you can pound on the wall or the window and get our attention. Good luck getting Narcan on graveyard [shift] in R- 4 or -5.”

COs carrying Narcan is a good thing. Any kits they keep within arm’s reach are that much closer to the person overdosing, for whom a couple of minutes could be all the difference.

But the obvious way to reduce fatal overdose in prisons is to let prisoners carry Narcan. In the maximum-security living units, like those in WCC’s Reception (R) Center, this is the only way to reduce fatal overdose.

Nearly everyone in prison in Washington State spends a few months in the R-units. WCC is the reception center for all 14 state prisons, where everyone coming into the system gets processed from the county jails.

In the general population living unit where I’m housed, we have “dry cells”—no toilets. So at night our doors are closed but not locked, since the bathroom is down the hall. If someone’s cellie is overdosing to the point of needing Narcan, they can run to the dayroom and find a CO, even during the graveyard shift.

“Here, you can pound on the wall or the window and get our attention,” McCracken told Filter. “Good luck getting Narcan on graveyard in R-4 or -5.”

Everyone in the R-units is locked inside their cells at all times except for meals; one 40-minute window each day for yard; another for gym; and a 20-minute shower three days a week.

The R units are “wet cells.” R-1, -2 and -3 are older, and their doors have bars. In an emergency you could probably get a CO’s attention by sticking out your arm or waving a towel. R-4 and R-5 have solid doors. In an emergency the only thing you can do is yell, and there’s so much yelling in prison all the time that COs aren’t inclined to get up and go see what the problem is.

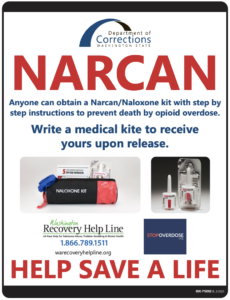

Top photograph via North Carolina Department of Public Safety. Inset graphic via Washington State Department of Corrections.

Show Comments