Just before the New Year on December 27, a federal judge ruled that the state of Georgia did not have to restore 98,000 people to the voting rolls. Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger had removed 308,753 voters on December 16—and voting rights group Fair Fight Action filed a federal lawsuit that same days, seeking a temporary injunction.

In his ruling, US District Court Judge Steve C. Jones said that Fair Fight Action did not prove the state had violated the constitutional rights of the removed voters. He did, however, instruct the state to do more to warn people if they are being removed.

About 189,000 of the voters removed by Raffensperger had either moved or could not receive mail, and Fair Fight Action did not contest this. But the group, led by Stacey Abrams, a former Democratic Georgia gubernatorial candidate, did contest the removal of about 120,000 other voters claimed by the state to be “inactive”—meaning they had not voted in recent elections and were not responding to state communications.

The state restored 22,000 people to the voter rolls on December 19, claiming they had essentially been removed in error. Those people are still classified as “inactive,” however, and must now respond to the state within a certain time-frame in order to be eligible to vote. That left the 98,000 remaining people who were the subject of the December 27 ruling.

So altogether, about 287,000 potential Georgia voters were removed. To put that number in context, it is more than five times the margin of victory that Republican Brian Kemp had over Abrams in winning the Governor race in November 2018.

Knowing that their state has a long history of suppressing people’s right to vote—above all, people of color and low-income residents—activists in Georgia are forming new coalitions to organize and educate. These coalitions include drug policy reformers who are aware of the intersections between this issue and their core concerns.

“This is part of a long-term strategy by the state of Georgia to disenfranchise voters for this election,” Erica Darragh, a board member of Students for Sensible Drug Policy, told Filter. She noted that “Georgia is a swing state in this year’s election because of massive demographic shifts that have been happening for years.”

In addition to her drug policy reform work, Darragh organizes with the Sunrise Movement to educate people about climate action in Georgia. Young people form its main base of support. And people aged 18 to 39, Darragh noted, will form about 37 percent of the electorate in 2020—a potentially decisive voting bloc.

Darragh believes that a partnership between the drug policy reform and climate justice movements is long overdue. “Achieving a Green New Deal and ending the War on Drugs go hand-in-hand,” she said. “The War on Drugs is part of larger systems of oppression that we can start to dismantle when we pass a Green New Deal with equity and justice provisions.” She is working on partnering with organizations like HeadCount to host voter registration drives at Sunrise rallies and events. HeadCount has registered 600,000 voters at music concerts since it launched in 2004.

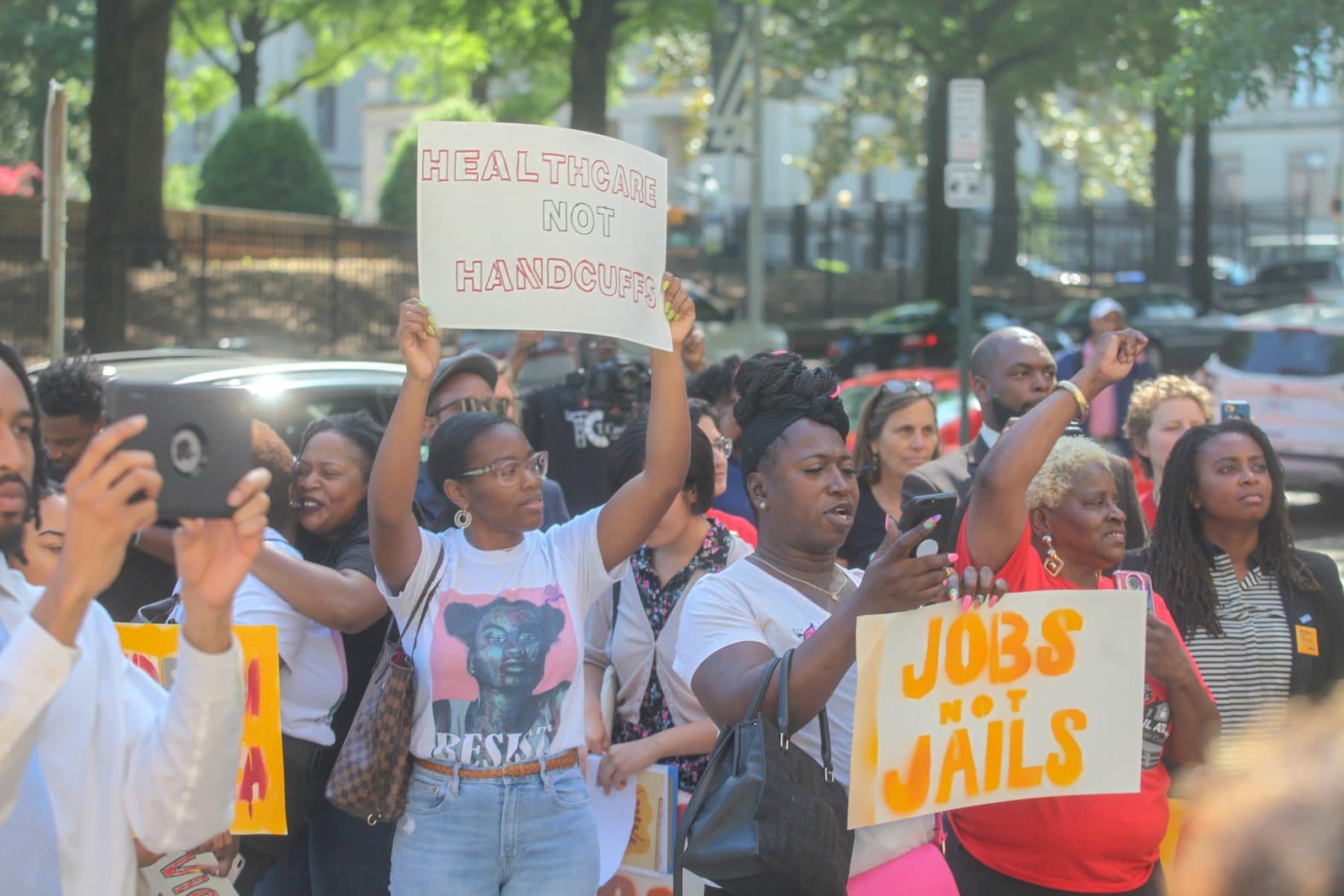

Other Georgia activists are focusing on voting rights as part of criminal justice reforms. Women On The Rise (part of the Racial Justice Action Center), an organization founded by formerly incarcerated women of color, is educating formerly incarcerated people about how they can register to vote. The groups is also campaigning to restore voting rights to people with felony convictions, and even to get electoral ballots distributed in county jails.

“We focus on changing policies and informing folks who may not know about basic disparities because of social or racial injustices,” Bridgette Simpson, a community organizer for Women On The Rise, told Filter. “We are making people aware that voters are being purged, especially formerly incarcerated people who might not even know they have the right to vote.”

Women On The Rise and its partner organizations notably succeeded in closing a city jail in Atlanta, which the city is in the process of repurposing into a community center. Partnering with organizations and activists to hold voter registration drives, produce community events, and canvass door-to-door is a key part of the group’s ongoing work.

One of the worst consequences of voter suppression is psychological, Simpson said. “When people participate and don’t see the results, they get discouraged. The biggest thing is encouraging people to believe that their voices and votes count. But it’s not easy—so many people have already lost hope.”

Whatever the outcomes at a state level, organizing voters can help to achieve local reforms, Darragh noted. She cited the fact that while the state legislature’s Republican supermajority has stonewalled on marijuana reforms, 12 jurisdictions in Georgia have effectively decriminalized. Eleven percent of Georgians now live in a jurisdiction where they won’t go to jail for marijuana possession.

“Our state government is so detached from what our people want,” Darragh said. “The voter suppression campaigns have been so intense for so long that it just doesn’t represent us. So we’re asking people to think about how we can change drug policy by organizing at the local level, county-by-county.”

Image of Racial Justice Action Center protest in Atlanta via Facebook.

Show Comments