Vermont has unveiled operating guidelines for overdose prevention centers (OPC), which will include smoking consumption areas and potentially mobile sites. The state became the third to authorize OPC on June 17, in a dramatic eleventh-hour override of the veto issued by Governor Phil Scott (R). The Vermont Department of Health published the guidelines September 13, two days before its deadline to do so.

The state’s first OPC is expected to be a brick-and-mortar location for Burlington, but the legislation also allows for mobile units. These are defined as OPC “that can move locations, such as a van or a bus, or a non-permanent unit … that operates for less than 180 days.” The only other requirements are that mobile OPC have access to have potable water and phone service, and not permit smoking consumption “indoors.”

The guidelines require OPC to have an area for smoking drugs, like fentanyl or cocaine, operational within 12 months of opening. If it won’t be ready in time, the health department will allow an extension of up to another 12 months. OPC must also have “fire-proof ash disposal for smoking-consumption areas,” plus fire extinguishers. If indoors, smoking areas will be required to have a separate ventilation system from the one serving the rest of the building. The latter requirement in particular has been a logistical barrier to including safer smoking in OPC proposed in the United States and Canada.

Neither fentanyl nor cocaine are smoked using a combustion process, i.e. burning them with flame like a cigarette. Combustion destroys them, which is the main reason that claims of fentanyl-laced marijuana never turn out to be true. “Smoking” in this context actually means “vaping,” which doesn’t produce smoke nor ash the way cigarettes do.

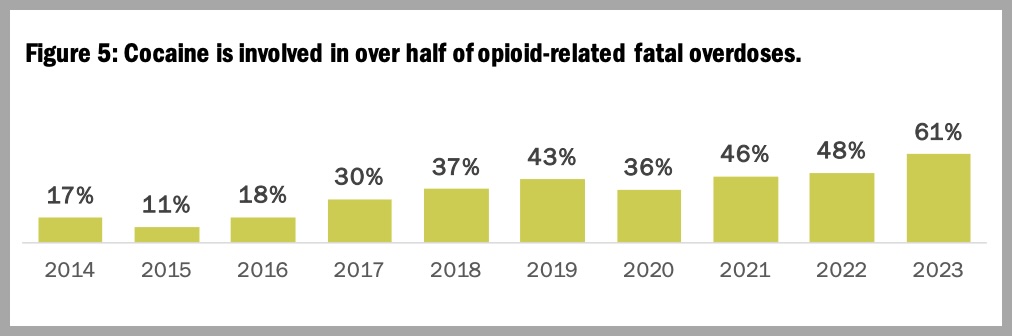

Fatal overdose in Vermont has increased by 500 percent over the past five years. An April 2024 summary from the state health department showed around 95 percent of overdose deaths involved fentanyl. Almost two out of every three overdose deaths in 2023 also involved cocaine, a sharp increase from previous years.

In 2019, more than half the autopsy reports for people who died of overdose listed the route of administration as injection, while 15 percent listed smoking. In 2021, the most recent year for which data are available, 37 percent of overdose deaths were associated with injection while the rate for smoking rose to 29 percent.

This lines up with shifts in patterns of use across North America, particularly in the West. As fentanyl rapidly supplanted heroin in many regions during the COVID-19 pandemic, harm reduction organizations began recording a mass shift from injecting to smoking as people attempted to mitigate a higher-potency supply.

Rhode Island, which in 2021 became the first state to authorize OPC through a legislative process, is expected to open its first site before the end of 2024. It will include inhalation booths to accommodate safer smoking, and goes further than Vermont in explicitly protecting “inhaling, exhaling, burning, vaporizing or carrying” any substances intended for consumption. Including via “electronic vaporization devices,” though commercial vapes run too hot to work well for a lot of substances other than nicotine.

Minnesota quietly authorized OPC in May 2023 with Senate File 2934, which authorized funding for up to 15 “safe recovery sites” offering harm reduction services “including but not limited to: safe injection spaces; sterile needle exchange.” The legislation doesn’t mention smoking, but the sites won’t actually allow on-site consumption of any kind when they first open; the state health department has committed to adding the service “eventually.”

Health Commissioner Dr. Mark Levine testified that while deaths at OPC were “rare,” the sites weren’t an appropriate use of funds. There has never been a recorded death on-site at an OPC.

OnPoint NYC, the nonprofit operating what are currently the only two authorized OPC in the US, has ventilated communal smoking rooms. At one of its two Manhattan locations, most participants inject opioids; at the other, most smoke crack cocaine. Both sites operate under city jurisdiction; New York State has stalled on OPC authorization for years.

In April, Vermont Commissioner of Health Dr. Mark Levine testified that while on-site deaths at OPC were “rare,” they weren’t an appropriate use of opioid settlement funds for a rural state like Vermont. (There has never been a recorded on-site death at an OPC.)

“Dedicated rooms to allow for smoking may change the design and expense and other logistical considerations,” Levine told legislators, and “it is not clear how an occasional visit from a van can produce desired outcomes in a condition that requires frequent use.” Burlington is the state’s most populous city. Any mobile units would have fixed schedules, similar to how many syringe service programs conduct outreach.

In July, the American Civil Liberties Union sued Gov. Scott’s administration for withholding public records—emails exchanged with Levine—that could show “political interference by the Scott administration to undermine” OPC. Levine altered the final report of the state Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee before it was presented to legislators, removing the recommendation to allocate funding to OPC.

Top image via State of Massachusetts. Inset graphic via Vermont Health Department.