Unless you are a smoker who has tried and failed to stop, I don’t think you can really appreciate how demoralizing “quit attempts” can be.

I had my first cigarette at the age of 15. I smoked at least 20 cigarettes a day for 26 years. I enjoyed it, but gradually came to wish I could stop. I tried numerous methods: nicotine patches, nicotine gum, self-help books and good old “will power”—and failed every time. I nearly cracked it once, using the Nicorette Inhalator—a device sharing some characteristics with vaping—but the cartridges were expensive and yet again, I slipped back to smoking.

I’ll never forget the day in summer 2011 that I was persuaded to give vaping a try by my son, when we came across a cigalike promotion stand while walking through London’s Euston Station. With all those “failures” behind me, I simply didn’t believe the salesman when he said that he gone from 20 to just one combustible cigarette a day, thanks to the product he was selling. Just a typical salesman, I thought!

I realized later that he had almost certainly been telling the truth, and I still feel sorry for doubting him.

As I mentioned, I had been demoralized. Bear in mind that the officially sanctioned smoking cessation method in the UK, nicotine replacement therapy (including the patches, gums and inhalators of my failed attempts), has a success rate of only 7 percent—or a failure rate of 93 percent. Add to that the moralistic tone of the times we live in, when it is acceptable to stigmatize people for their “poor” lifestyle choices, and being a smoker can be really quite miserable.

Amidst recent reports that the e-cigarette company Juul reached Its $10 billion valuation four times faster than Facebook—and the manufactured panic over youth vaping and tobacco industry involvement in reduced-risk nicotine products—we might need reminding of one very important point.

Vaping was built by smokers, for smokers. And it developed in spite of government interference and without big industry involvement. Consumers have been at the heart of the vaping revolution—and if we’re to maximize the incredible potential of tobacco harm reduction for current and future smokers, at the heart is where we need to stay.

Why Vaping Works for Us

Vaping works, for millions of us: Recent UK statistics show that 1.7 million people here have successfully stopped smoking through vaping. A significant proportion will be “accidental quitters”—like my friend Paula, who bought an e-cig just “for a giggle”, or Andy, who just wanted something to use in his car. These people hadn’t wanted to stop smoking, but found vaping more appealing and effortlessly transitioned, missing out the miserable failed-quit-attempts stage entirely!

Why is vaping such a good alternative to smoking? It’s not just because it delivers nicotine—if that were so, nicotine replacement therapy would be doing the job. Vaping works for us because we can customize our experience and make it pleasurable. It works because it shares some of the enjoyable aspects of smoking: inhaling and exhaling, the hand-to-mouth ritual, the sociable aspect of spending time with other people who enjoy it too.

Stopping smoking is often referred to as “giving up”—suggesting that smokers have to abandon something they like doing. However, many of us vapers feel we have replaced smoking with something just as (or even more) pleasurable, so there is little or no loss. Vaping is empowering, so it’s no wonder we defend it so tenaciously.

Shopkeepers have become the new stop-smoking services; official stop-smoking services have seen a drastic drop in footfall.

A remarkable aspect of the take-up of vaping is that it has spread mostly by word of mouth. According to the 2017 Eurobarometer 458 report, 15 percent of smokers in the EU have tried e-cigarettes. However, advertising for these products is severely restricted by the Tobacco Products Directive, so consumers aren’t discovering this new product in that way.

Instead, they are learning about it from one another. When I started vaping my partner soon took it up too, then vaping spread to his circle of friends, then to their circles of friends. To begin with we mostly had to buy our products online, but gradually we started to see vaping shops in our town centers, often started by someone who had personally made the switch.

These shopkeepers have become the new stop-smoking services; in the UK, official stop-smoking services have seen a drastic drop in footfall since vaping became widespread.

It is important to note that it was small and medium businesses which sprang up to sell us our vaping products, which were manufactured in factories in Shenzhen, China. Tobacco companies only became involved in the reduced-risk nicotine product market relatively late, and control little of the market today.

“Big Tobacco has only a small, and declining, share of the vaping market,” David Sweanor, an industry expert and chair of the Advisory Board for Centre for Health Law, Policy and Ethics at the University of Ottawa, tells Filter. “Globally, on a cigarette-equivalent basis, I’d estimate the cigarette companies have less than a 20 percent share, and in the US market somewhere in the range of a 10 percent share.”

Nevertheless, opponents of harm reduction love to cite tobacco industry involvement—as if this somehow invalidates the lives being saved.

Vaping Culture and Organizing

I started vaping using cigalikes, but they were prohibitively expensive for me and not very satisfying, so I turned to some vaping forums for help. If you ever need reassurance that the internet can be a decent place, head over to the new user corner on a vaping forum and watch experienced vapers patiently giving non-judgemental advice to newcomers.

Forums are also where vapers network, discuss products and develop them. Many of the mass-produced vaping devices around now—especially the squonkers and drippers—have origins in products first designed and built by skilled vapers and adapted in response to feedback from other vapers.

The forums opened my eyes to the wonderful world of tailoring my own vaping experience—but also to the threat of vaping not being around for much longer.

These modders helped to rapidly evolve e-cigarette inventor Hon Lik’s device. Dr. Danko, an Australian vaper, snus user and doctor, describes it well:

“From 2012 to 2014 vaping was taking off at an exponential rate worldwide. A community of underground hardware hacking pioneers had already been working for years to improve the early e-cigarettes. Using their distributed intelligence they connected through Internet forums freely ….creating open-source, unpatented nicotine delivery systems. They tinkered in their sheds to increase the power, capacity and e-liquid delivery. Almost every innovation in vaping can trace its origin to these unsung, unpaid public health heroes. Their inventions were adopted by new nimble Chinese e-cigarette companies who started mass producing the devices and millions of smokers began using them.”

The forums opened my eyes to the wonderful world of tailoring my own vaping experience—but also to the threat of vaping not being around for much longer. As recently as 2013, the government of the UK—despite the country shaping up to be one of the world’s biggest tobacco harm reduction success stories—was unbelievably pushing for the EU to make e-cigarettes medicinal-only, so that vapes would no longer be on the general market.

We vapers responded, sending thousands of letters telling our personal stories to MEPs, and the European Parliament overturned the proposal—a stunning success.

This grassroots campaign was the start of vaping activism in the UK. It was followed by the Efvi initiative, a Europe-wide campaign to get one million signatures to force the EU to reconsider putting e-cigarettes into the Tobacco Products Directive—placing arbitrary limits on the nicotine strength in e-liquids and the sizes of tanks and bottles, and severely restricting advertising.

Vaping is huge now, and will only get more so. It’s estimated that almost 55 million adults worldwide will be vaping by 2021.

The Efvi campaign did not succeed in this target, and we are stuck with the TPD today. But it was crucial for building networks between vape advocates in various European countries. The threats to vaping keep coming—not least in the United States—but we are getting much more organized now. The International Network of Nicotine Consumer Associations currently represents 36 consumer organizations worldwide, with more members in the pipeline.

The last year or so has also seen consumer organizations from lower- and middle-income countries becoming much more vocal, which is exciting to see, especially as tobacco harm reduction is generally not yet well accepted in these regions.

Vaping is huge now, and will only get more so: Euromonitor, a market research group, estimates that almost 55 million adults worldwide will be vaping by 2021. The vast majority will view themselves as people who happen to vape rather than as vapers, still less vaping activists. Still, there are myriad vaping-focused networks on social media, and the real-world community is vibrant, too, for example at vape expos and meets.

And while I have focused on vaping, because that was my route into tobacco harm reduction, I’ve recently become much more aware of snus—a pasteurised oral tobacco estimated to be at least 95 percent, and probably closer to around 99 percent, less risky than smoking. Snus is overwhelmingly responsible for Sweden having the lowest lung cancer rates in Europe.

Snus users and vapers turn out to have a lot in common: We enjoy doing what we do, we are into flavors and how our products look, some of us feel that our lives have been transformed, and we face the same challenges from bad science and ill thought-out regulation.

Crucially, there also are networks of experts who challenge the often-atrocious coverage of vaping studies. Most mainstream media outlets are very careless on vaping, and many studies are themselves poorly conducted, and apparently designed with the finding already in mind. Researchers often appear not to understand how vaping works or how devices are used.

As Carl Phillips, a doctor and vaping advocate, has said: “Most papers about vaping could be vastly improved by simply soliciting the input of a few vapers.” Scientifically literate vapers are a force to be reckoned with—and, as they tend to specialize on just this one subject, can be extremely knowledgeable.

Being labeled a “tobacco company shill” or “addict” is par for the course.

We mostly recognize that regulation is inevitable, and that to keep it from being disastrous we need to help to shape it by placing ourselves firmly into the conversation. This squares with a principle demanded throughout the wider harm reduction movement: Nothing about us without us.

Advocacy, Stigma and Choice

Us British advocates have found constructive engagement with people in public health to be a very effective strategy. UK health organisations such as Public Health England and the Royal College of Physicians have concluded that e-cigarettes are around 95 percent safer than combustibles, and the government’s Tobacco Control Plan has committed to supporting “consumers in stopping smoking and adopting the use of less harmful nicotine products.”

We have a perennial funding problem, as public health bodies will not engage with those who have accepted money from the vaping or tobacco industries. I now work for the New Nicotine Alliance UK advocacy group, the country’s only active consumer organization for reduced-risk nicotine products. We operate on a shoestring, but it is still an ongoing struggle to fundraise, because we have to rely entirely on private donations.

Not everyone is prepared to work with us constructively. Some people in public health have behaved appallingly. Being unfairly labeled a “tobacco company shill” or “addict” is par for the course, and we are regularly blocked on Twitter by public health people, even if we haven’t engaged with them.

Vaping advocates don’t give up their time to keep safer products as an option for ourselves; experienced vapers and snus users can already be entirely self-sufficient. Our motivation is simply to keep choices open for current and future smokers.

Choice is a key word. Smokers are already stigmatized enough, and we want no part in that. Most consumer advocates do not want to beat smokers into stopping; we respect people’s right to smoke, but want them to have the option to use safer products to not smoke, should they wish.

People who use tobacco harm reduction products are and always should be at the center of this conversation. Because before the big business, before the science, we were the ones helping each other—and that remains the case today.

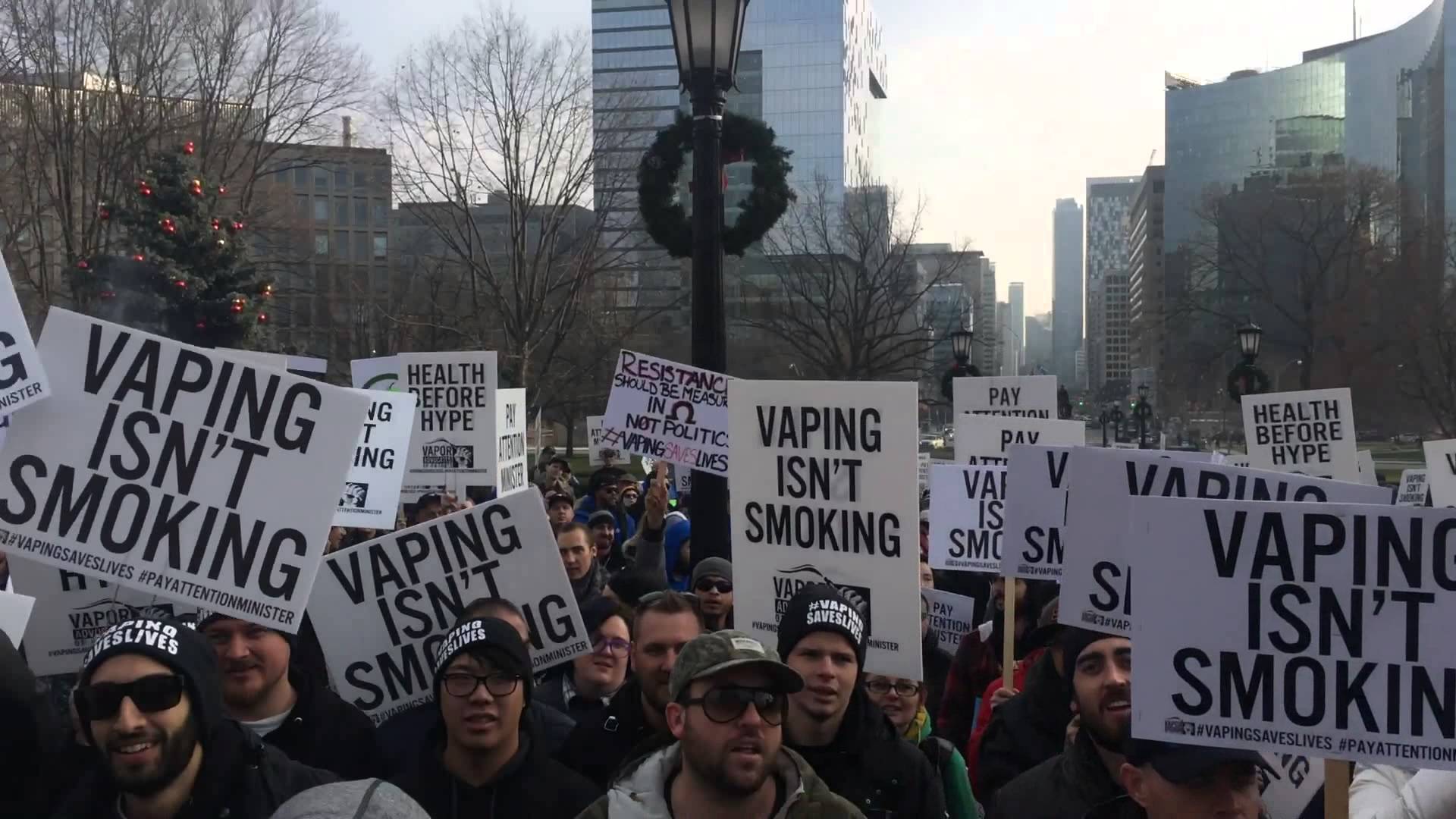

The top image, via Youtube, shows vaping advocates protesting in Ontario, Canada in 2015.