Last May, as physicians, drug users and harm reduction workers grappled with a new and perplexing arrival in Philadelphia’s rapidly evolving open-air drug markets—bags of heroin and/or fentanyl contaminated with the powerful synthetic cannabinoid 5F-ADB, known as “K2”—I received an early morning call from a regular source in Kensington’s drug-user community.

“I have something for ya you’re really gonna like,” he said excitedly. “When can we meet? I’ve been carrying it all night.”

I had no idea what “it” was. But by then I was getting pretty well known as “that journalist who tests drugs and posts the results.” So I was accustomed to people giving me small samples of their drugs to test.

After the first outbreak of street dope contaminated with synthetic cannabinoids, which sickened nearly 200 people in September last year, people were literally handing me full bags (sometimes several) of drugs they wanted nothing to do with.

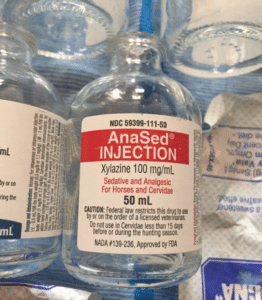

But I was not expecting what my source brought me that humid day last May. Reaching into his duffle bag, he produced a gallon ziplock bag containing eight empty bottles that had contained xylazine—a non-opioid tranquilizer used to sedate large animals. Referred to locally as “sleep cut,” xylazine has been used as a cutting agent for heroin for some time in cities like Philadelphia and New York.

It is currently not scheduled in the US. Obtaining the drug requires only a veterinarian prescription, which is a piece of cake if you own a few horses, know someone who does, or just know which palms to grease. The bottles I obtained from my source were from two different providers—both veterinary labs located in the Midwest that sell a variety of items for the equine community. (Here is a fact sheet on the drug from one of the labs it was sourced; to be clear, the distributor would have no way of knowing how the product was being put to use).

It is currently not scheduled in the US. Obtaining the drug requires only a veterinarian prescription, which is a piece of cake if you own a few horses, know someone who does, or just know which palms to grease. The bottles I obtained from my source were from two different providers—both veterinary labs located in the Midwest that sell a variety of items for the equine community. (Here is a fact sheet on the drug from one of the labs it was sourced; to be clear, the distributor would have no way of knowing how the product was being put to use).

Xylazine is approved by the FDA for animal use only. That’s because it’s known to be harmful in humans. Clinical findings reported that xylazine users presented limb skin lesions, ulcerations and greater physiological deterioration than users of heroin only. Deaths where the drug is named are rare, however. A 2012 paper attributed just 22 deaths to xylazine; recently, a suburban Philadelphia paper included a rare mention of xylazine death in February, when it attributed two overdoses to the “new” drug. (The victims also had fentanyl and acetyl fentanyl in their system, which suggests to me it’s not xylazine that’s new, but more likely testing for it by the county lab).

Recreational human use of xylazine—both by itself and mixed with heroin and/or cocaine—reportedly first emerged in Puerto Rico, where xylazine has been described as the “zombie drug” by the media due to its heavy sedating effect. This short documentary from National Geographic illustrates the drug’s pervasiveness n Puerto Rico and its effects.

One American former heroin user I spoke with lived in Puerto Rico when she began using drugs. She told Filter that she remembers traveling to a Midwest state (where “tar” heroin would have been all that was available at the time) and thinking “there’s something wrong with the dope here.” She’d become so accustomed to “tranq dope” that it changed her perception of what heroin should feel like.

That said, not everyone likes the combination. The tranq dope that xylazine produces in combination with heroin is favored by some, and disdained by others. Louis, a Philadelphia Latino in his mid-30s, told Filter that he prefers the energy he gets from pure opioids, but that he knows people who prefer the added sedation of tranquilizer cut.

Asked how she avoids it, she said she depends on word of mouth, or else buys several different heroin brands to diversify her personal supply.

“I hate it” said Jess, a heroin user I met in Kensington on April 1, when asked about tranq dope. Jess has a full-time job with a major retail outlet, but said she has trouble working when using tranq dope, due to its sedating effect.

Asked how she avoids it, she said she depends on word of mouth, or else buys several different heroin brands to diversify her personal supply. This is a tactic employed by more IV drug users these days, as market disruption has all but eliminated any expectation of consistency in product supply. Some would rather risk arrest traveling to different drug-dealing “sets” than risk spending all their money on one brand.

Others deliberately obtain a bag or two of tranq dope for their “bedtime” shot, believing it more likely to hold them through the night.

But like many other substances mixed into illicit-market supplies, xylazine is often unavoidable, whether people wish to take it or not.

Other examples of this happening crop up all the time. For instance, “speedball” use spiked throughout 2017 in Philly as well as much of the Northeast and as far west as Ohio—yet many injection drug users I spoke with last year were convinced that the $5 bags of white injectable powder being sold as cocaine were instead “bath salts,” a generic name used to describe dozens of popular “substituted cathinones”—a class of mild-to-potent synthetic stimulants. When I started carrying around cocaine test strips I surprised more than a few: Every single bag of suspected cocaine that I tested came back positive for the drug (which of course doesn’t rule out the possibility it was cut with some other stimulant as well).

That situation continues, with coke quality picking up, according to my sources. The DEA says that record coca production in Colombia has actually created a surplus of cocaine in Philadelphia, and on March 20, US Customs agents at the Port of Philadelphia logged their biggest seizure of the drug in two decades—netting nearly 1,200 pounds of coke bricks hidden in a shipping container.

More than a dozen people stood bent over or else lay splayed out on the sidewalk; all were in a state of total or almost total unconsciousness.

Several weeks after receiving the largest single piece of physical evidence anyone I spoke to had seen confirming the presence of xylazine in the Philly heroin supply, I was reminded why the medicine is called the “zombie drug.”

I learned through word of mouth that a new dope sample had just hit the street that was loaded with the sedative.

“Look around,” a middle-aged heroin user in a wheelchair told me near the major intersection of Kensington and Allegheny Avenues just after sundown. “You can tell who got one, right?” He laughed as we scanned the horizon. More than a dozen people stood bent over or else lay splayed out on the sidewalk; all were in a state of total or almost total unconsciousness.

“Like any street drug, I always recommend heating up your cooker to kill off any bacteria and to help break down any impurities.”

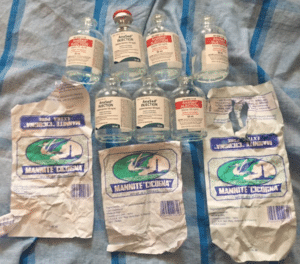

In all my time covering the heroin trade I had never previously seen it. My source said he found the bottles discarded by the roadside along with two paper “Mannite” wrappers. “Mannite” (Mannitol) is a type of alcohol sugar and is one of the most common cutting agents for heroin; it’s about half as sweet as lactose, dissolves easily, and can be toasted lightly in an oven producing the tan color that IV drug users often claim (erroneously) proves the drug in the cooker is heroin (as opposed to fentanyl, which they say dissolves clear).

Unlike with other commonly used intravenous drugs and cutting agents, there is no easy way to test for the presence of xylazine. This presents a problem for harm reduction workers.

Unlike with other commonly used intravenous drugs and cutting agents, there is no easy way to test for the presence of xylazine. This presents a problem for harm reduction workers.

“Xylazine, commonly known as ‘tranq’, and other animal tranquilizers, obviously were not manufactured for the intent for human consumption. Therefore, there may inherently be some forms of bacteria or fungi that are bodies are not equipped to fight.” said Shawn Westfahl, a long-time harm reduction service provider and advocate in Philadelphia, who says he frequently encounters IV drug users with the skin lesions commonly associated with xylazine use.

So Westfahl, whose work includes giving overdose reversal trainings, defers to standard harm reduction practices when asked how he has been dealing with the spike in tranq dope.

“Like any street drug, I always recommend heating up your cooker to kill off any bacteria and to help break down any impurities,” he told Filter. “And as with any suspected overdose, administer naloxone and always support the person’s breathing by giving them rescue breaths if they are not breathing, or by rolling them into the recovery position if they are.”

Xylazine may be less dangerous than some other common heroin adulterants, but it still poses real risks. And its widespread presence in Philly and beyond is yet another illustration of the inherent instability and riskiness of unregulated drug markets.

Correction, April 18, 2023: A previous version of this article included a calculation that mischaracterized xylazine dosing.

All photos by Christopher Moraff