It’s widely documented that decades of punitive criminal justice and drug policies have led to the US becoming the world’s leading incarcerator. We are slowly beginning to come to our senses, realizing mass incarceration does not make us safer—nor is the cost tenable—and nationwide, the push for comprehensive criminal justice reform is strong.

Likewise, as our country faces co-occurring crises of overdose and suicide, there is broad consensus on both sides of the proverbial aisle that we must urgently address how we respond to both addiction and mental health. However, entrenched stigma and discrimination around people with substance use and mental disorders has been baked into our health and social service systems. So, too, has racism.

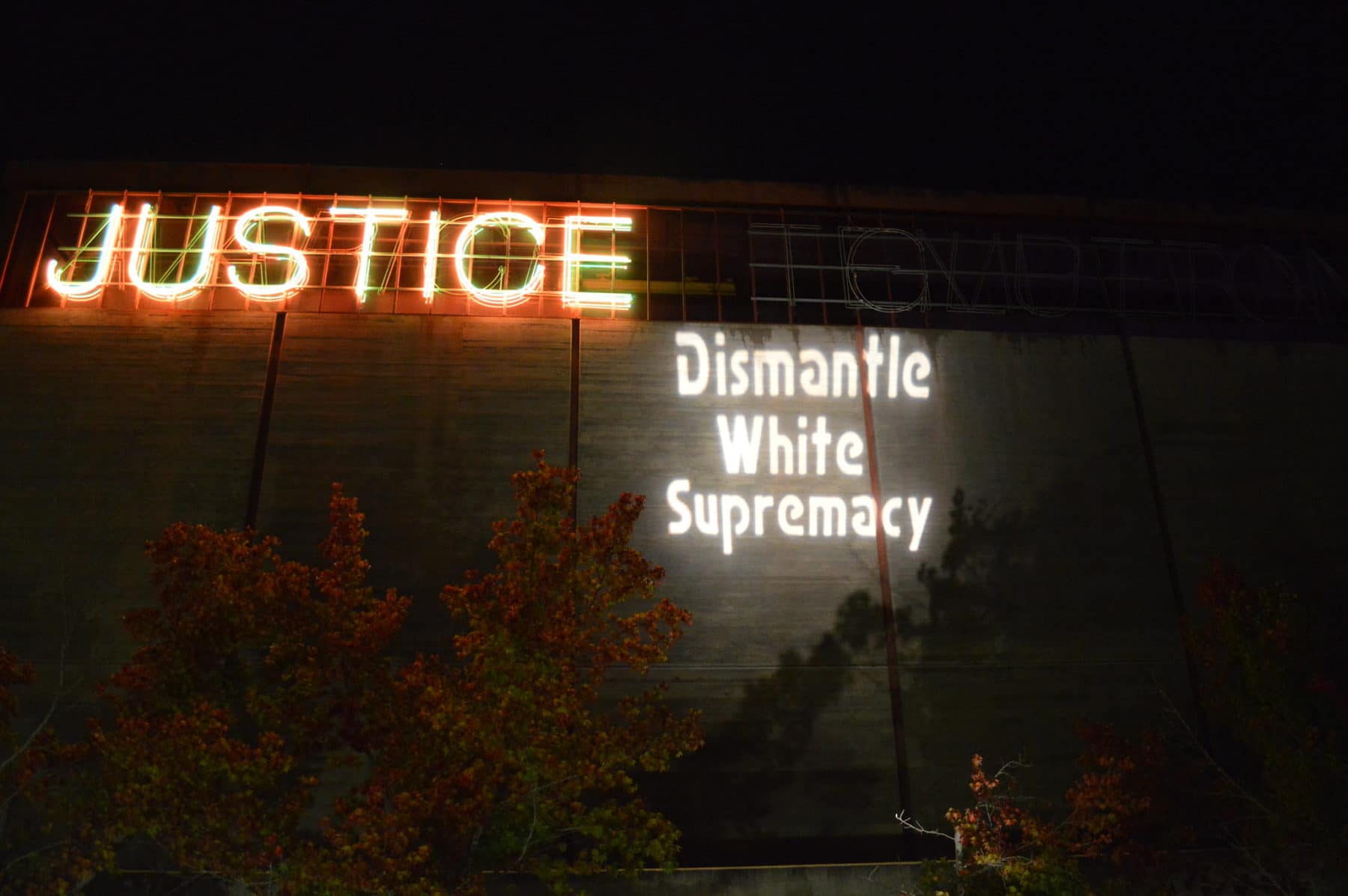

Unless we acknowledge the deeply ingrained, continuing legacy of slavery and anti-black racism in both our public health and criminal justice systems, we will never make the transformational change that is needed.

For those of us who have been fighting on the front lines for the past three-to-four decades, it has been surreal to see the change in attitudes.

If we continue with siloed reform approaches that do not acknowledge how the criminal justice and health systems are inextricably woven together—and into the fabric of institutional racism—we will only repurpose unequal systems that reinforce prejudiced perceptions on who is of “value” and who is not.

For those of us who have been fighting on the front lines of healthcare, drug policy and criminal justice reform for the past three-to-four decades, it has been surreal to see the change in attitudes, the bipartisan support, and the new funding resources directed to address the many consequences of the War on Drugs.

At the Legal Action Center (LAC), we fight discrimination against people with histories of addiction, HIV/AIDS and criminal records, and we have been working on these issues since our founding in 1973—at the height of the heroin epidemic, the beginning of mandatory minimums, and the inception of national drug policy focused on supply instead of demand.

We already knew racism was a core element in the foundation of many of these policies. Now, more and more people are understanding the intricate manifestations of a racial caste system, illustrated, for example, by Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow and in Ava DuVernay’s documentary, 13th.

In 2018, LAC launched “No Health = No Justice” as a specific response to growing criminal justice and health policy reform movements in recent years that have failed to recognize the core importance of racism, and the intersectionality of the systems. As we strive to dismantle decades of punitive and racist laws and policies, we must first understand how these structures were established. In this respect, the campaign is fortunate to be guided by Dr. Samuel Roberts, a leading scholar on the historical intersection of race, drug policy and incarceration. Through “No Health = No Justice,” we can explicitly articulate the intersectional and racial justice lens essential to this work.

Institutionalized Racism and Inequity in Healthcare

With the advent of Black Lives Matter and other grassroots movements, as well as increased media attention on the violent, disproportionate policing of black and brown communities, national understanding of the systemic racism within the criminal justice system has grown. Understanding of the systemic racism in public health policy, however—and of the undeniable link between criminal justice, health inequities and racial discrimination in this country—still lags behind.

The reality is that both health and justice opportunities have been historically—and are still presently—mainly accessible only to certain groups of Americans, namely those who are white and middle-upper class.

“Compared with whites, members of racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive preventive health services and often receive lower-quality care.”

Americans receive varying levels of healthcare or are wholly denied access based on race and socioeconomic status. According to a 2016 report by the Kaiser Family Foundation, “data shows that people of color continue to face significant disparities in access to and utilization of care,” and “despite coverage gains under the ACA, nonelderly Hispanics, Blacks, and American Indians and Alaska Natives remain significantly more likely than whites to be uninsured. Overall, people of color account for more than half (55%) of the total 32.3 million nonelderly uninsured.”

A 2018 study by the Commonwealth Fund reported that, “compared with whites, members of racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive preventive health services and often receive lower-quality care.” As an appalling example of what this disparity translates to, ProPublica reported data in 2017 showing that, “a black woman is 22% more likely to die from heart disease than a white woman, 71% more likely to perish from cervical cancer, and 243% more likely to die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related causes.”

These disparities predictably persist when looking specifically at substance use and mental health disorders. “As hard as it is for anyone to get proper mental health care in the United States, it’s even harder for racial, ethnic, religious and gender minorities,” the National Alliance on Mental Illness states.

What’s more, our nation has criminalized these health issues: There are more people with substance use disorders in the criminal justice system (6 million) than in treatment (2.3 million). And, as you might anticipate, the impact on black and brown, low-income communities is even greater. Despite comparable drug use, African Americans are incarcerated for drug-law violations at nearly six times the rate of whites.

Clearly, both criminal justice and health policy reform must acknowledge and account for systemic discrimination and inequity, so we can address the root causes of these disparities rather than attempt to simply alleviate the symptoms.

Racial Bias and the Overdose Crisis

Today’s opioid-involved overdose crisis has garnered a national spotlight not only because of the havoc it is wreaking on individuals and families (in 2017, there were more than 47,000 overdose deaths involving opioids, and over 70,000 total overdose deaths), but because of the impact it has had on the white, middle-class population that society sees as victims of opioid addiction.

The juxtaposition of the white victim against the black criminal is insidious and reinforces national drug policy.

A recent study by JAMA Internal Medicine assessing racial and income disparities in the prescription of opioids in California suggests that the initial higher concentration of white Americans with opioid use disorder (OUD) was itself the result of systemic racism. A lack of healthcare access, as well as discriminatory treatment based on race and class largely shaped who was prescribed opioids in the first place.

Now, synthetic opioid-related deaths (primarily fentanyl) outnumber other opioid-related deaths. And the impact has been considerable in communities of color. According to the CDC, black people experienced the largest increase in opioid overdose deaths among any racial group from 2016 to 2017, with a 25.2 percent surge.

Moreover, local opposition to developing treatment programs has inadvertently created a dearth of addiction and mental health services in the very communities that now so desperately need them.

Meanwhile, continuing media coverage of the overdose criss perpetuates the myth that addiction for white, middle-class individuals is due to the overprescribing of legal drugs, but addiction for black and brown individuals is limited to illicit street drugs.

The juxtaposition of the white victim against the black criminal is insidious and reinforces national drug policy that favors treatment for white people and incarceration for people of color.

Making the Health and Justice Connection

The jail and prison system has in many instances thus become the de facto healthcare provider for low-income individuals of color with substance use disorders and mental health issues. Between 65-85 percent of incarcerated individuals have a substance use and/or mental disorder.

The sad reality is that efforts to close Rikers in New York City, for example, can’t be accomplished unless we account for the fact that the jail is also part of the city’s addiction and mental health service delivery system. This uncomfortable truth is rarely mentioned in jail closure discussions. And the continued criminalization of these health issues has certainly fueled our country’s mass incarceration crisis. There are more people in jails and prisons today for drug offense than the number of people who were in prison or jail for any crime in 1980 (2.2 million individuals are currently incarcerated, and more than 70 million Americans have a criminal record).

In most communities, there is little-to-no meaningful linkage between the criminal justice and healthcare systems.

We must destigmatize and treat addiction and mental illness as the medical conditions they are—across the board. Achieving racial equity in healthcare and criminal justice reform means working with community healthcare providers to create an understanding of the particular health challenges associated with incarceration, and how care for incarcerated people can be instrumental in reducing recidivism.

This is a key priority for “No Health = No Justice,” and we are working closely with community health leaders like Dr. Kima Taylor, who shares her experience and expertise with physicians and other healthcare providers across the country.

We know that people reentering the community following incarceration often need immediate and sustained healthcare, but that in most communities, there is little-to-no meaningful linkage between the criminal justice and healthcare systems. Moreover, there are few opportunities to connect people to care as an alternative to incarceration—despite clear evidence that this approach is key to improving public health and public safety priorities, not to mention reducing public expenditures.

As evidenced by the impact of New York’s 2009 Rockefeller Drug Law reforms, long advocated for by LAC, diversion to treatment produced an 18 percent drop in recidivism within two years of treatment. Based on this and other examples, the Pew Center on the States estimated in 2011 that New York could save over $42 million if it reduced recidivism by just 10 percent.

It is clear that without a cross-sector approach—one that recognizes the relationship between systemic racism, criminal justice and healthcare policy—we cannot hope to reverse the current epidemics of overdose, suicide and mass incarceration which tax the nation’s spirit and budget.

A Harm Reduction Model

Harm reduction, a model that aims to reduce the negative consequences of substance use by prioritizing tackling root causes and the conditions of use, along with the use itself, has been favored by advocates for some time—perhaps most notably during the AIDS crisis. But it has only recently gained more mainstream attention. Expanding upon this model in “No Health = No Justice” means also addressing the harms that society inflicts on the individual. Historically, resistance to harm reduction approaches has involved the difficulty of facing the inequities of race and drug policy that reverberate all the way to today’s overdose crisis.

Much drug policy and criminal justice reform work has historically been led by people who have never been personally affected—and that is deeply problematic. “No Health = No Justice” prioritizes working with advocates whose efforts are directly informed by lived experience.

Exponents, an almost 30-year-old New York organization co-founded and led by Joe Turner, a person in long-term recovery and one of the few black men running a treatment program, is one such pioneer. Exponents has integrated harm reduction into a client-centered treatment model that has never required abstinence and incorporates community-building and political advocacy. Turner and other harm reduction educators and practitioners understand the unique challenges that drug users face on a daily basis and are able to “meet them where they are” to provide meaningful support. This knowledge is critical to developing approaches that will be effective at achieving and maintaining improved health and healing at the community level.

The Rallying Cry: No Health = No Justice

In addition to working with leaders with lived experience and harm reduction practitioners, “No Health = No Justice” will convene treatment advocates, criminal justice reform advocates, healthcare providers, other practitioners in the field and policymakers to work in coordination with one another in numerous states.

Injustice lives in both systems, and they are inextricably linked.

“No Health = No Justice” aims to increase access to preventive healthcare in communities, as well as diversion to treatment at all phases of justice involvement, including linkage to care upon leaving incarceration. Our work also includes recognizing the handicap of criminal records, so we strive to enhance civil rights protections to prevent discrimination in employment, housing, education and other necessities of life. This is integral to breaking the cycle of poor health, incarceration, and economic and social instability.

Time and again, those that suffer the most at the intersection of health and justice have been low-income black and brown communities. Reminiscent of the protest chant, “No justice, no peace!” our campaign is a rallying cry for all to heed—injustice lives in both systems, and they are inextricably linked.

We believe it is only through a united and intersectional approach that we can truly build more equitable health and criminal justice systems and make the change that is so urgently needed.

Photo of protest projections in San Diego via Backbone Campaign on Flickr/Creative Commons

Show Comments