Women drink and take drugs because it’s fun. We do it to be bulletproof. To be more intimate, or more intimidating. To become ourselves-to-the-power-of-10. To experiment. To enhance sexual performance, or work performance. To bolster relationships with peers and partners. To be social. To belong. To lose weight. To unwind. To self-soothe. To wake. To sleep. To observe ritual or tradition. To take control. To lose control. To rebel. To conform. To remember. To forget.

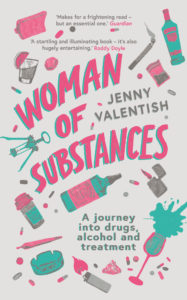

For most people, for the most part, substance use is a manageable aspect of life. My book, Woman of Substances, takes the drug out of the crosshairs and looks instead at the behavior. But the journey towards its publication taught me a lot about the prejudices that apply to both drug use and gender.

In late 2008, I pitched the book to an Australian agent. She suggested we thrash out the finer details in person, so I flew to Sydney the day before our appointment, dropped my suitcase at an absent friend’s apartment, and went out with another mate to celebrate my impending deal.

The next day I came to, naked, with the front door open and a bad feeling. The agent had given up waiting in the cafe after an hour. Later, on the phone, we agreed the time might not be right. More pressingly, I had to find my friend’s cats and book a new flight. Don’t worry–we all made it home.

In late 2009, I pitched it to a different agent. By then I had quit drinking, but I didn’t know who I was anymore. The agent wanted an assurance that there would be “redemption” in the book–and there I was fantasizing about buying a length of rope. She wanted a memoir with a neat story arc, while I wanted answers: Why am I governed by impulsivity? Why the constant restlessness? Why the urge to always press the big red button, even when it flies in the face of common sense?

I saw the commonality between my more distressing experiences and the path that plays out for many women. There were repeated themes of abuse, sexual assault and violence.

I thought the answers ought to come from evidence-based research. So in 2015 I brought the adapted idea of a research–memoir hybrid about women and substances to a publisher. It was now approaching seven years since I’d quit drinking, and I hoped to have the benefit of hindsight and distance. Even so, as the project progressed, it became way more personal and taxing than I had anticipated.

This was because the more experts I interviewed–doctors, neuroscientists, researchers, clinicians, policymakers–the more I saw the commonality between my more distressing experiences and the path that plays out for many women whose substance use has become problematic. There were repeated themes of abuse, sexual assault and violence. It seemed negligent not to explore those parts of my history.

I travelled to treatment facilities, universities and transitional residential homes, to piece together my interviewees’ individual expertise and form a bigger picture about the issues particularly pertinent to women. These issues include: self-medicating anxiety and depression; the link with eating disorders and self-harm; the propensity to be drawn to abusive situations; the stigma around dependent mothers; the physical issues that women in particular can develop; and the fact that the treatment industry is still geared towards the male experience, aka “the norm.”

Through sharing what I had already learned with each interviewee, I realized that perhaps this bigger picture was one that hadn’t fully been seen before.

I did question whether the world needs another middle-class white woman writing about her addiction issues.

In Australia, unlike the US, the disease model is only popular in private rehabs and 12-step meetings. Here, policy and government-funded treatment largely aligns to a public health model, which posits that addiction is learned behavior and a complex interaction between an individual’s biological, psychological and environmental factors–and the drug. Australia’s national drug strategy is of “harm minimization,” with abstinence at one end of the spectrum and safer use at the other. (This applies of course, in the context of a country in which drug use is still largely criminalized, which is inherently harmful.)

Language is person-centred, not drug-centred, i.e.: ‘person affected by drug use’, ‘problematic substance use’, ‘drug-related harm’, and ‘levels of dependency’. These are terms that don’t create an us-versus-them divide, or keep a person forever in their ‘addict’ box, and I embraced them.

What’s become obvious to me is that addiction arises from a melting pot of factors spanning both nature and nurture. It can be influenced by availability; cultural messages; peer pressure; policy; social learning; adversity; mental illness; and temperament or personality traits. It’s a biopsychosocial soup, and that’s the script the book follows.

I did question whether the world needs another middle-class white woman writing about her addiction issues, and a journalist at that. There are so many books out there that fit this mold, just the tip of the iceberg being Caroline Knapp’s Drinking: A Love Story; Tania Glyde’s Cleaning Up; Alice King’s High Sobriety; Ann Marlowe’s How to Stop Time: Heroin from A to Z; Marya Hornbacher’s Wasted; Rosie Boycott’s A Nice Girl Like Me; Leslie Jamison’s The Recovering; Maia Szalavitz’s Unbroken Brain; Cat Marnell’s How to Murder Your Life; Elizabeth Wurtzel’s More, Now, Again; and Sarah Hepola’s Blackout.

Of course every perspective–above all, those supported by evidence–can be valuable. With my book, since there were already so many expert voices, I wanted one case study to focus on in depth, and I felt ethically uncomfortable putting someone else under the spotlight. So I used my own vignettes as the jumping-off point for deeper research–while making efforts not to let this narrow the book’s relevance, for example by including the work of Indigenous researchers and looking at the experiences of sex workers and trans women.

Radio hosts pounce: ”When did you last have a drink, Jenny?”

If I had one mission other than to examine the experiences of women, it was to question the rock bottom-to-recovery narrative so beloved by the media, which reinforces to us that a person was walking trash before they quit substances, but once they’ve quit and repented, we can accept them back into the fold.

Traditionally, any book with an addiction-memoir element should involve the author turning over every rock to examine the nasty things that squirm beneath. Then there’s a hasty crescendo, in the final chapter, to redemption. The narrator is suddenly a goodly sober, saved by their eternal pledge to recovery. The reader, only a second ago skidding in gory detail, is now showered with rose petals. Or pelted with sobriety chips.

I’m a flawed narrator, then. When the Australian edition of the book came out in 2017, I talked about never having used the word sober, because of very occasional drug use. By the time the US version came out last month, my eight years sans booze had come to an end.

Call it closure, but writing the book seemed to mark the end of an era, particularly when added to the rigorous therapy, self-examination and redesigning of my life that had taken place over those years.

Let’s face it, though, the timing was awkward. On the occasions I’ve done media and have mentioned the fact that I drink now, radio hosts pounce–”When did you last have a drink, Jenny?”–in the kind of hopeful tone that suggests I should sob, “Just before I came on air!”

That’s to be expected though, and it’s a useful conversation to have, since accounts of people who have experienced dependence reintroducing substances (or only cutting back in the first place) are too rarely heard–or allowed.

Now I regularly talk at drug and alcohol conferences, as well as at public events, and I’ve found that not framing substance use as “failure” is a more popular concept than you might imagine.

Woman of Substances is available now in hardback.

Main photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash

Show Comments