When I moved to Italy for school in August 2022, I brought a three-month supply of testosterone, syringes and needles—the maximum my pharmacist in the States would give me. I also brought with me a doctor’s letter, to ensure there wouldn’t be trouble at customs.

Due to my mistaken belief that there was a legal restriction on picking up more than a 90-day-supply of Schedule III drugs in my state, as is the case in many areas, I assumed that I wouldn’t be able to get six months’ worth at another pharmacy and didn’t bother to try.

But I wasn’t too concerned about getting more. Considering I’d been officially diagnosed with gender dysmorphia in the States, had undergone gender-affirming surgery and had taken hormones for years already, I thought that finding a new doctor to continue my care would not be difficult. I assumed I could simply ask the school doctor for a referral to an endocrinologist, who would continue prescribing my testosterone.

I was wrong. It turned out, I would first need an official diagnosis of gender dysmorphia from an Italian specialist. The waiting list for an appointment was quite long. Thus, when my medication ran out around finals during my first semester, I found myself forced to acquire a new three-month supply, through means which shall go undescribed for legal reasons.

By the time they finally gave me the papers, I’d run out of my meds again. And this time, I had no immediate way to procure more.

Once my appointment for a diagnosis finally came around, things seemed to go well. They assessed me for various mental health issues and asked me a long list of questions about my gender and sexuality. The well-documented nature of my gender and transition certainly helped. But smoothly as the process went, it wasn’t exactly quick.

My initial appointment was simply for intake; I was then required to make another for the tests; and a third just to be presented with my diagnosis. For some reason, that diagnosis-and-paperwork appointment was also delayed by about two weeks.

By the time they finally gave me the papers I needed in order to book an appointment with an endocrinologist—months away—I’d run out of my meds again. And this time, I had no immediate way to procure more.

Unsurprisingly, the sudden cessation of a medication I’d been taking since April 2021 made me quite sick.

Already, when I took my final injection in March 2023—a quarter of the usual amount—I was extremely out of it, having cut back to preserve my dwindling supply. I felt achy and gloomy.

Usually, I spend hours reading and doing homework in the mornings. But without testosterone—and even with extra tea—I mostly just sat around feeling depressed. A heavy, dense “brain fog” descended. I could barely follow lectures or conversations. Speaking or reading any language aside from my native one became almost impossible—not helpful when you’re studying classics and seeking to communicate with friends who don’t speak English.

I was plagued by wretched headaches. I rapidly lost the strength and weight I’d gained in recent months.

I even temporarily fell out with one friend, who was baffled by my extreme tiredness and sudden inability to form comprehensible sentences in Latin—the only language we share, and one he had helped teach me, making my struggles seem like a personal affront. I hadn’t yet come out as trans to him, and my attempts to explain the situation without outing myself before I was ready only made him overly concerned about my health.

I made ditzy mistakes when trying to work, and was barely able to keep my head up in class due to exhaustion. I was plagued by wretched headaches. Attempting to exercise was hopeless. When I tried to do push-ups, my muscles hurt and seemed to lock up, causing me to sink to the floor. I rapidly lost the strength and weight I’d gained in recent months. My insomnia also worsened significantly. This, on top of everything else, led me to be on edge and snappy.

Despite the perfectly logical medical explanation for all of this, I felt like an absolute failure.

I also feared that the symptoms would last forever, or at least until my body started naturally producing standard amounts of “female” hormones again—a thought which terrified me, because I desperately hoped to avoid menstruating. Assuming that this situation could last several months, I feared that I would fail my exams if I remained in this state.

During those long, lonely, sleepless nights, I began googling the matter. This led me to various anecdotes and evidence that yes, testosterone withdrawal exists. But I also found out that some of my worst symptoms were likely to last only around a week or two. Having a timeline soothed me significantly; pain is more bearable when you know it’s temporary. Being able to count down the days gave me some sense of control.

Around a week before my May appointment, I got my period for the first time in years.

Still, even after my acute withdrawal symptoms ended in April, I didn’t feel like myself. The exhaustion and insomnia never quite resolved. I begged the school doctor to help me find a specialist who could see me sooner than the one I’d booked for June. Thankfully, he managed to call in a favor on my behalf, bringing forward my appointment to early May—critically, before my exams.

Around a week before my May appointment, I got my period for the first time in years. The pain seemed much worse than previously. I dealt with this as best I could, borrowing hygiene products from my roommate and downing over-the-counter pain relievers. The psychological pain wasn’t as bad as I’d feared, perhaps because I’ve had top surgery and “pass” pretty well. I could bear it, although I would’ve preferred not to.

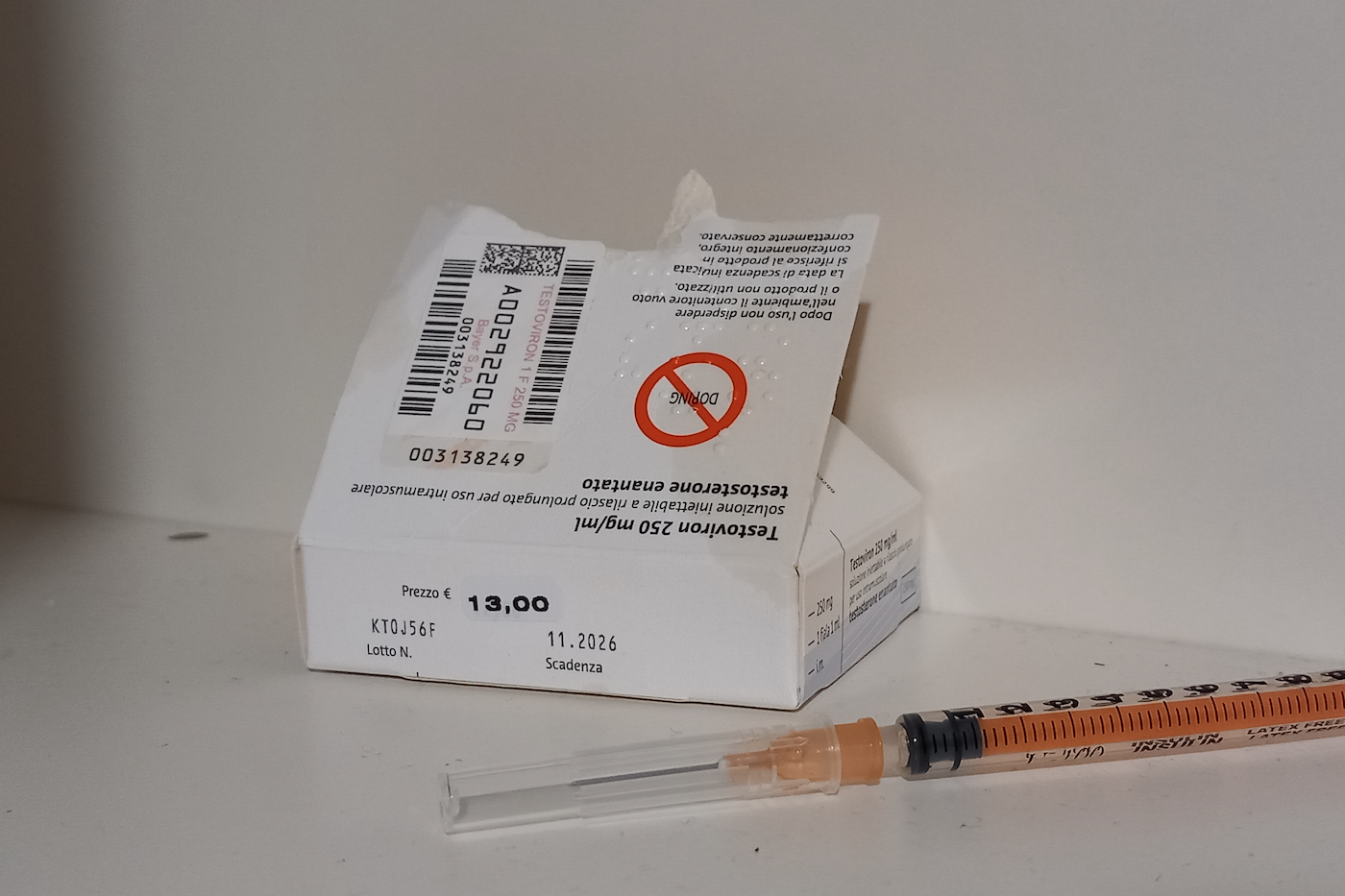

The appointment itself went surprisingly well. Somehow, the doctor was wholly unaware of my recent struggles to access my medication. When I told her I hadn’t taken hormones in five weeks, she told me I could take my next dose as soon as I got home. She prescribed me a four-month supply, sending the prescription to a sleek, well-lit pharmacy only a few blocks away. While a six-month supply is standard in Italy, she wanted to see how I was feeling on that dose and order blood work before prescribing more.

This prescription was for a monthly injection, as opposed to the weekly one I’d been on before. I’ve found this much more convenient because I don’t need to take my meds and needles with me when I travel. Also, getting needles and syringes turned out to be extraordinarily easy: In Italy they’re over-the-counter, so you just have to walk into a farmacia and ask for the right size.

Unfortunately, it took multiple months of being on medication for my periods to cease again. And even now, although I feel much better, I’m still working on rebuilding the muscle mass I lost.

Why can’t they just let us take our meds in peace?

Things turned out fine for me eventually, largely because I’m privileged enough to be able to access doctors. But a more understanding attitude towards hormone prescribing could have averted months of strife.

I’m allowed to carry bulk bottles of the deeply unpleasant and potentially dangerous amantadine I was briefly prescribed for my tardive dyskinesia. Pharmacists never insisted on only giving me three months at a time. Why not treat testosterone similarly? The same question stands when it comes to limits set by insurers.

Privileged kids who move to Italy to study have little to complain about compared to many other people at risk of losing access to necessary medications and experiencing debilitating withdrawal, as well as the pain of watching your body soften and become feminine again. Many transmasculine people experience far worse, when testosterone is criminalized in many contexts in the United States.

The DEA’s threats to end telehealth prescribing of controlled substances pose a serious danger because so many of us access our care through Planned Parenthood and other telehealth services. At the moment, telehealth prescribing has been temporarily extended through 2024. But thanks to right-wing outcry and attempts to restrict gender-affirming care, many patients—minors especially—are already losing access to the medications they need.

This is all in spite of—or, perhaps, because of—the fact that gender-affirming care significantly lowers the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts amongst transgender people.

Why can’t they just let us take our meds in peace?

Photograph by M.L. Lanzilotta

Show Comments