“The Tenderloin is a beautifully complicated area. It’s rich in all sorts of intersecting narratives. Sadly, some people fear it, some avoid it.”— Paul Harkin, HealthRIGHT 360.

In December, San Francisco Mayor London Breed declared a state of emergency in the Tenderloin (TL), a neighborhood which has long been home to some of the most disenfranchised people in the city. At a news conference with police officers lined up behind her, Breed, a Democrat, unleashed a “tough on crime” tirade that was positively Reaganesque. “The reign of criminals who are destroying our city, it is time for it to come to an end. And it comes to an end when we take the steps to be more aggressive with law enforcement—more aggressive with the changes in our policies and less tolerant of all the bullshit that has destroyed our city.”

To that end, she is giving the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) even more policing powers, and wants to funnel more money to them in overtime funding.

What is on offer for the TL residents who are struggling with combinations of homelessness, unemployment, addiction or mental health issues? “I was raised by my grandmother to believe in ‘tough love’—in keeping your house in order,” Breed wrote in a Medium post, “and I believe we need a little of that, now more than ever.”

How about a press conference that calls for “tough love” for landlords or real estate speculators?

Tough love is code for punishment and prison. Thousands of people in and around the TL literally don’t have a house to “keep in order.” They sleep in cardboard boxes in front of stores, or live in tent encampments (urban camping) or cars (vehicle residency). It is not a choice and it’s not their fault. Their enemy is the cost of housing in San Francisco, which is famously, outrageously, unaffordable.

Why doesn’t Breed take aggressive steps to bring more apartments under rent control, and immediately move people into hotel rooms or the 40,000 vacant homes in the city? How about a press conference that calls for “tough love” for landlords who charge extortionate rent—or for real estate speculators who buy up rent-controlled buildings and evict tenants so they can convert them into luxury condominiums for the rich?

Central to the mayor’s Tenderloin Plan is ramping up the drug war under the well-worn guise of “safety” and “protecting the children.” After meeting with families in the TL, she said it’s a neighborhood full of children (like most neighborhoods) and referenced a shooting near a park where children play.

“Without evidence, officials frame unhoused people as dangerous to housed people, particularly their children,” stated the California ACLU in its October 2021 report, The Legal War Against Unhoused People. “They are condemned as a threat to public safety, and a form of blight that needs to be swept up, disappeared, and excluded from places where housed people gather.”

“Public drug use isn’t about drug use. It’s about not having a living room where you can get high with your friends.”

This is what the mayor’s Tenderloin crackdown is all about. “We are not giving people a choice anymore,” Breed said. “We are not going to just walk by and let someone use [drugs] in broad daylight on the streets and not give them a choice between going to the location that we have identified … or going to jail.”

Jeannie Little, the cofounder of the Harm Reduction Therapy Center (HRTC), a mental health and substance use treatment organization that provides services in the Tenderloin, pushed back on the idea that using drugs in public spaces is really a choice.

“Public drug use isn’t about drug use,” she told Filter. “It’s about not having a living room where you can get high with your friends. If you see people completely laid out, unconscious, possibly overdosing on the street, you might be seeing an accident, you might be seeing someone getting the best rest they’ve had in days, or you might be seeing someone who is suffering from the long-term ravages of poverty, homelessness and trauma.”

San Francisco officials, substance use experts and social services organizations oppose Breed’s plan. “The War on Drugs has produced exactly the conditions you see in the Tenderloin today, having contributed to mass incarceration, generational carceral trauma, and the dehumanizing conditions for so many people…” wrote Dr. Vitka Eisen, the CEO of HealthRIGHT 360, in a statement on the mayor’s declaration.

“There have been times of a massive police presence, hundreds of arrests in a day. All that malarkey, it doesn’t work.”

For Paul Harkin, HealthRIGHT 360’s director of harm reduction services, the mayor’s announcement smacked of cognitive dissonance. “You don’t couple compassionate care with a harsh police response. People need to be cared for, not brutalized,” he told Filter. Harkin has been working in the TL for over 20 years, witnessing numerous law enforcement crackdowns. “There have been times of a massive police presence in the Tenderloin, hundreds of arrests in a day. All that malarkey, it doesn’t work.”

“It has a lot of unintended consequences, too,” he continued. “Increase in overdose, a spread of drug activity to other neighborhoods, contested turf wars and the disruption of dealer supply chains.”

The mayor knows of one vital resource for people using drugs in public; safe consumption sites. She has publicly advocated for them since 2018. Her support is deeply personal. Breed’s younger sister died of overdose. If she had declared an overdose emergency, funded and opened dozens of safe consumption sites three years ago when she was elected, fewer people would be using drugs outside and far fewer would be dying. Instead, Breed abandoned the fight.

San Francisco has among the highest per capita overdose death rates of any US city. Over the past two years, there have been over 1,360 such fatalities—an average of nearly two a day, and more than double the total COVID-19 death toll.

The “bullshit” that Breed said she will no longer tolerate in the TL is actually a full-blown humanitarian catastrophe decades in the making. COVID-19 made it exponentially worse. And those who stand with the unhoused and the dead need to call bullshit on Breed.

It is jaw-dropping to witness all this preventable-but-not-prevented human suffering,then walk a few blocks and behold world-class museums.

When I spent time in the Tenderloin in summer and fall 2021, I would see people sitting on sidewalks and huddled in doorways, searching for veins to inject. I saw people without shoes, shirts and pants unconscious on the ground. Some people were incoherent or in clear distress. Tents were lined up block after block, and there were people pushing wheelchairs and shopping carts filled with blankets, tarps, clothes and electronics. Trash, rotted food and human excrement lay on streets that the city doesn’t clean nearly enough.

It is jaw-dropping to witness all this preventable-but-not-prevented human suffering, and then walk a few blocks and behold world-class museums, artsy coffee houses with comfy couches, and a vendor charging $7 for a pint of organic blueberries. San Francisco is one of the 10 richest cities in the world and has the most billionaires. This high-tech dystopia is a monument to 40 years of neoliberal policies, of leaving basic human needs like housing to brutal market forces.

At the same time, however, the Bay Area has always been a progressive leader in harm reduction-based drug policies and creating new, innovative services. In addition, San Francisco has long been a center of power for the LGBTQ community’s fight for liberation. During the AIDS crisis, activists confronted discriminatory mental health and medical systems. They created a vast structure of social services programs, assisted housing for people living with HIV, and drug treatment grounded in the harm reduction principle of “meeting people where they’re at.”

But the power of the politically connected California real estate industry and the gutting of federal funding for new housing by more than 80 percent have hobbled Housing First ambitions. Article 34 of the state Constitution also requires voter approval for any public housing project to be built in a community. Passed in 1950, it unleashed a vicious Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) movement. Several attempts to repeal Article 34 have failed. San Francisco’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing must also share blame. Hundreds of affordable homes are unoccupied because of excessive documentation requirements, computer glitches, and staff turnover.

The health consequences of an epic failure to adequately house people year after year are dire, with greater morbidity and mortality rates among people who are unhoused.

Delivering services outside is vitally important, but can’t substitute for permanently housing people and the stability and dignity that brings.

Social service organizations in the TL work to provide things that are inside a home outside—on the streets and sidewalks, in parks, plazas and parking lots and via mobile vans. There are portable toilets, sinks and shower stalls, soup kitchens, pop-up free food, laundry trailers and safe sleeping villages. Health and mental health care are provided outside of hospital, clinic or office-based settings, too. There is a mobile pop-up therapy van, Street Overdose Response Teams and the Street Medicine Team, who write buprenorphine prescriptions on the spot and provide routine medical services. Care Through Touch offers free chair massage.

Creating and delivering such services outside is vitally important, but it can’t substitute for permanently housing people and the stability and dignity that brings.

Single room occupancy hotels dot the TL— “the centerpiece of low-income housing,” as Harkin called them. They have a mixed reputation. Some are well maintained with private bathrooms and provide social services to tenants, while others are dilapidated, dangerous and filthy, with shared toilets in hallways that don’t work and owners who don’t give a fuck. “So many who live there have died of an OD,” Harkin said. “Why don’t we have safe consumption sites run by peers in every SRO? There are other services offered in hotels—healthcare, training and employment. But can we start with the keeping them alive part in the era of an unprecedented overdose crisis? This is simple shit that we know works.”

No Place to Go

Hostile perceptions of unhoused people are inextricably linked to an unprecedented crisis in public sanitation. Human waste in public spaces angers communities, makes the housed public lose empathy and can trigger police “sweeps” and criminalization.

Complaints about people relieving themselves on the streets, in doorways, and on the subway have been increasing for years, but the COVID-19 lockdown greatly exacerbated them. People without housing depend on an inadequate number of free restrooms in libraries, parks, transit hubs and drop-in centers. Overnight, as a result of the pandemic, they closed. “You probably smell me now,” said Richard Parry, who is unhoused. “Human waste is everywhere. It’s not because we are lazy. It’s because people aren’t letting us in.”

“We are human, we need a place to go to the bathroom.”

With mass homelessness, defecating and urinating in public places becomes inevitable because it isn’t a choice. But public urination is a crime and can result in a civil summons, a fine or arrest. It can land a person on a sex offender registry. Interviews with people on the streets reveal that the inability to access toilets is one of the most degrading aspects of their lives.

To address the issue, the San Francisco Public Works department created the “Poop Patrol” and the Pit Stop program, which operates portable toilets staffed by paid attendants. The Tenderloin has the most requests to clean up human waste.

A woman in a leopard print jacket at the corner of Eddy and Turk put it bluntly: “We are human, we need a place to go to the bathroom.” Keisha,* who was living in her van, told me she uses the Pit Stop toilets when she isn’t at work delivering food for Meals on Wheels.

Rows of gender-neutral toilets with solar panels on top are conveniently located across from a tent encampment and are integrated into the busy, noisy landscape of the TL’s “Little Saigon,” where a roast pork or tofu bahn mi at the hole-in-the-wall Saigon Sandwich shop costs a reasonable $4.75.

JCDecaux, a for-profit company that operates in collaboration with several nonprofit organizations, has installed 25 self-cleaning toilets with sinks across the city. The French designed bathrooms are compact, oblong metal structures painted army-green with capitalized letters in gold “TOILET.”

Walking up Market Street to check one out in the Castro, I passed the SF LGBTQ Center building, painted a deep purple, rainbow flags whipping in the wind. Further along was a whimsical, Keith Haring-style mural painted on a boarded-up store window.

The pandemic had hollowed out the once-vibrant scene. With the exception of the charming, vintage streetcars that noisily travel up the middle of the wide street, it was eerily quiet, with little pedestrian foot traffic. Shops, offices, theaters and restaurants had closed. In their place were tent villages and groups of unhoused people socializing on sidewalks. In a colorful painting on the side of a building, the gay rights activist Harvey Milk was smiling and holding a megaphone: “Hope will never be silent.”

I spoke with Jimena, a friendly bathroom attendant employed by the nonprofit organization Civic. Years ago, she explained, “People had to pay for a token to use the toilets, but the token machine kept breaking, so it was made free. At one point, the city shut them all down because people started living and using drugs inside of them.”

City officials reopened the bathrooms and staffed them with paid attendants, imposing a 20-minute time limit. Most attendants are people who were formerly unhoused or incarcerated. Jimena used this facility when she was living on the street. “It’s very beneficial. Without this bathroom people will go in public places,” she said. “The toilet and the floor is cleaned after every use,” she added with a touch of pride. “It’s durable. This is the Castro, so it’s open 24 hours a day. That’s why people who are homeless stay near here.”

“We don’t want people living inside … the bare bones design gets people to move along.”

Most modern public toilets in the US are designed to deter unhoused people, drug users and sex workers. The Portland Loo, a stand-alone public toilet used in numerous states, is an example of “crime prevention through environmental design” and hostile architecture. Law enforcement input was sought in its development, and it shows. The dull, gray structure is cage-like with a concrete floor and a toilet made of prison-grade steel. Metal slats at the bottom and top of the restroom are angled to minimize privacy and allow police surveillance. The bathroom can be ordered with blue lights “to prevent drug users from locating veins.” To prevent bathing or washing clothes, there is no sink. Instead, a spigot outside dispenses a timed amount of cold water.

“We don’t want people living inside … the bare bones design gets people to move along,” Evan Madden, the sales manager for The Portland Loo, told Filter. He is personally torn about drug use inside the loo, he said, and believes that it is a “human right to use a bathroom.” Madden noted that the city of Seattle didn’t install blue lights in the toilets they purchased because they can “cause more health problems.”

Urban Alchemy

The Tenderloin is full of openly hostile architecture. If there are any benches at all, metal dividers make it impossible to lie down. Building owners embed sharp steel “anti-homeless spikes” in flat surfaces to deter sitting or sleeping. Bus stops have no seats. In the 1990s, San Francisco removed all of the benches from Civic Center Plaza.

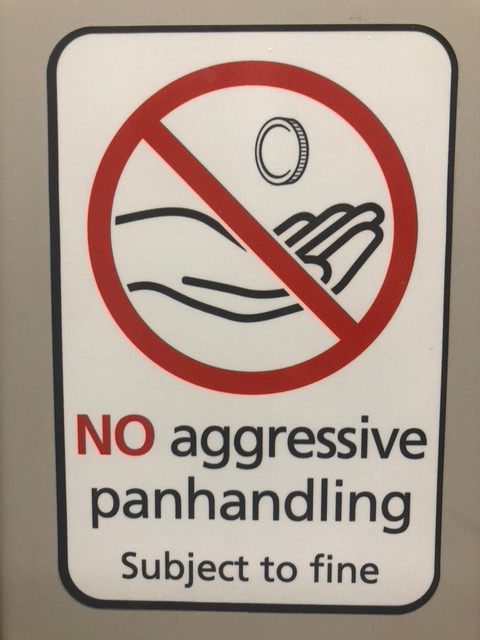

Negative signage like “No aggressive panhandling,” “No soliciting,” and “No camping” creates an unwelcoming environment for unhoused people. And that is the goal.

The Turk-Hyde Park in the TL is defined by this goal. Inside are manicured grass and trees, playground equipment and a wood trellis with benches and tables underneath. It’s a pristine, relaxing oasis in the city, but not for everyone. The miniature park is enclosed by high black metal fencing. One sign states, “Adults must be accompanied by a child except during permitted or programmed activities.” A second lists regulations with clear targets: camping and smoking is prohibited, “THIS PARK IS A DRUG-FREE ZONE” and no “wheeled conveyances other than strollers with children.”

Walking by Turk-Hyde at various times, I almost never saw parents with children inside. Directly across from the park on the sidewalk stood a row of orange and blue tents. Crammed inside and huddled outside were folks who could only gaze at the clean, beautiful, empty and forbidden space.

That park is where I met staff from Urban Alchemy (UA) for the first time. Wearing a black cap and jacket with a logo, Calvin explained that the organization employs former prisoners as “practitioners.” His job is to clean the park and make sure no one comes in who isn’t accompanied by a child. Calvin told me he interacts with a lot of homeless people. I pointed out the cluster of tents across the street and he said, “They don’t want housing.”

A few blocks away I talked to another UA employee who said he spent 43 years in the penitentiary. Lawrence described his job as providing security in the TL. I asked if that included deescalating conflicts. “I can’t because of my experience in the penitentiary,” he replied. “I walk away and get a coworker who can do that.”

Lawrence also expressed the view that homeless people don’t want housing. That notion, and “Why don’t they just stay in a shelter?” is something I heard over and over. Shelters have bad reputations. During the pandemic they became “congregate death traps,” as community organizer Shams “Da Homeless Hero” DaBaron put it. The complaints are valid. Who wants to sleep in a bunk in a warehouse-like room with a hundred other people? Theft of belongings is a problem, as are curfews and the lack of privacy. Personal safety is another reason shelters are avoided by many women.

“Fentanyl is all over the Tenderloin and we’ve reversed a lot of overdoses.”

Dozens of UA employees were visible in the TL, sweeping up trash and greeting people as they walked by. “I’m a harm reductionist,” said Diego, who wore a black Raiders face mask and introduced himself as an experienced peer advocate and former drug user. “Fentanyl is all over the Tenderloin and we’ve reversed a lot of overdoses.” A see-through plastic pocket in his lime-green reflective vest held a 4 mg container of Narcan nasal spray. Another hung from a chain around his neck just in case a second dose was needed.

Diego’s concern for the people he works with was obvious, as were the job’s difficulties. “I take work home with me,” he said. “Right now I’m looking for a woman who was reported missing and I heard that there is a guy raping women in the neighborhood.”

Urban Alchemy says that prison experience uniquely qualifies employees to work with vulnerable populations in the Tenderloin because they “share a special bond with society’s most vulnerable … because we see ourselves in their struggle,” and that long-term incarceration gives an “ability to read people in unpredictable situations.”

“They have a specific skill set you don’t find in the general population,” Dr. Lena Miller, UA’s CEO, told Filter in a phone interview. “You have to go through so much trauma and come out the other end and still find the light to have this skill.”

“When you are under stress and pressure for decades, you develop an exquisite sense of emotional intelligence and you learn how not to react,” she elaborated. “People say stuff on the street that is traumatizing, it’s nothing compared to prison.”

Incarceration is a singularly traumatizing experience. For those who’ve been in prison for decades, and especially in solitary confinement, the cumulative harm is devastating. And formerly incarcerated people need jobs, which they are legally denied. UA’s hourly pay rates are well above the minimum wage. “Our population reflects who is in prison,” Miller said. “Our workforce is 60 percent Black, 35 percent Latino and 10 percent white.”

“We are not a Trojan horse for the police, we are the buffer between the community and the police.”

UA therefore serves a need created by structural racism. Yet surviving the trauma, violence and deprivation of imprisonment doesn’t automatically qualify a person to work with vulnerable groups; in fact, it could be triggering and re-traumatizing. And stationing practitioners, who are disproportionately Black men, many on parole, in a chaotic, high-stress, environment while Mayor Breed is unleashing a law enforcement crackdown puts them at real risk.

Critics of Urban Alchemy argue, too, that practitioners perform another role: policing people experiencing homelessness and working with law enforcement to evict them from public spaces. Miller adamantly denies this: “We are not a Trojan horse for the police, we are the buffer between the community and the police.”

In Mayor Breed’s blunt speech in December, she said, “we can’t keep doing the same thing and expecting a different result.” Three months later, she announced she would do exactly that. More police have been assigned to the Tenderloin to arrest sellers and people using drugs if they refuse services. Over 100 cops patrol the neighborhood. The estimated cost for voluntary overtime is $175,000 a week.

“We don’t want them to die.”

The Tenderloin Linkage Center which is next to the UN Plaza, was created as a result of Breed’s emergency declaration to connect people with housing, drug treatment and mental health services. Early data showed that just 3 percent of people had been connected to those services. But there is a service there that, despite Breed’s dropping the ball, is finally available.

In a fenced-off area adjacent to the building, people are allowed to use drugs. It’s referred to as the “Privacy Area” and participants are monitored by trained staff who, in the event of an overdose, can respond with naloxone.

Vitka Eisen of HealthRIGHT 360, who is a former heroin user, described its purpose very simply. “We don’t want them to die.”

*All first-name sources are pseudonyms, to protect privacy at sources’ request.

Photographs by Helen Redmond.

Show Comments