Those of us incarcerated by the Georgia Department of Corrections got used to the drones a while ago. They’ve been dropping in drugs and other contraband for years, and still do. But in the early days of the pandemic they were almost redundant.

“We had so few officers that kids could just run to the fence and throw bundles of drugs over. It was crazy,” John, 50, told Filter. A retired playmaker—a boss, in the prison drug economy—he’s been incarcerated in GDC for 21 years. “And that was kind of fun, to party. But you didn’t know what you were getting.”

GDC warehouses around 50,000 people across 34 facilities. Under COVID, there was no gym time. No recreational programs. No religious services. No vocational programs. No routine. And an understaffing crisis so severe that no one was really watching.

“Drug use [went] astronomically off the charts,” Tony, 38, incarcerated for most of the past 20 years, told Filter. The supply itself evolved, quickly. “Prior to the pandemic, drugs were not like this.”

Harm reduction, as it’s thought of in the free world, is not a discussion here. This is partly because the drug supply is not fentanyl-based, and opioid-involved overdose isn’t necessarily the main concern. But it’s also because harm reduction, even as a movement that grows only in adverse conditions, still requires certain environmental factors in order to take root.

The understaffing crisis and the federal policies designed to ensure a continued supply of incarcerated labor create a different set of priorities for people trapped inside the system. Some of those priorities, like whether to reuse syringes, are the exact opposite of harm reduction. GDC has removed most of the reasons anyone would worry about their own long-term health, let alone someone else’s.

“Many of us aren’t going anywhere, ever,” Koti, 24, told Filter. “Trip out since we can’t get out.”

Mutual aid is a luxury; no one can afford it here. The solidarity that drug users have found with each other in the free world just doesn’t exist in prison, or at least not in Georgia prisons.

Filter spoke with 14 people incarcerated across 10 GDC men’s prisons. All names have been changed.

“The drug that has blown up since COVID is strips.”

Though the drug supply always varies from one facility to the next, the similarities tend to outweigh the differences. Going into the pandemic, the most prevalent substances—after nicotine—were K2, methamphetamine, Suboxone and in some places marijuana. The change to the supply since then has been system-wide.

“The drug that has blown up since COVID is strips,” Rabbit, 36, told Filter. “Simple.”

“Strips” doesn’t refer to any specific drug—just paper, soaked with anything cheap and accessible. Most strips are smoked, often by simply lighting a toilet-paper wick, blowing out the flame, placing a piece on top of the ember and inhaling. Or they can be rolled up into spliffs, vaped or placed into water that’s then injected.

So the term can also refer to, for example, K2, which had already replaced much of the marijuana supply because fewer and fewer people could afford that. A free world-size joint of real marijuana can cost upwards of $50; a strip of K2 is $2.

But as the pandemic deepened, funding from loved ones and other outside connections shrank away. The need for a still-cheaper tier of drug arrived just as the understaffing crisis made it easier to get ahold of cleaning supplies. The market veered sharply toward DIY strips that didn’t have to be smuggled in from the free world at all.

Amid what JD, 38, called “the great meltdown of the Georgia prison system,” people found what was even cheaper than K2: Raid.

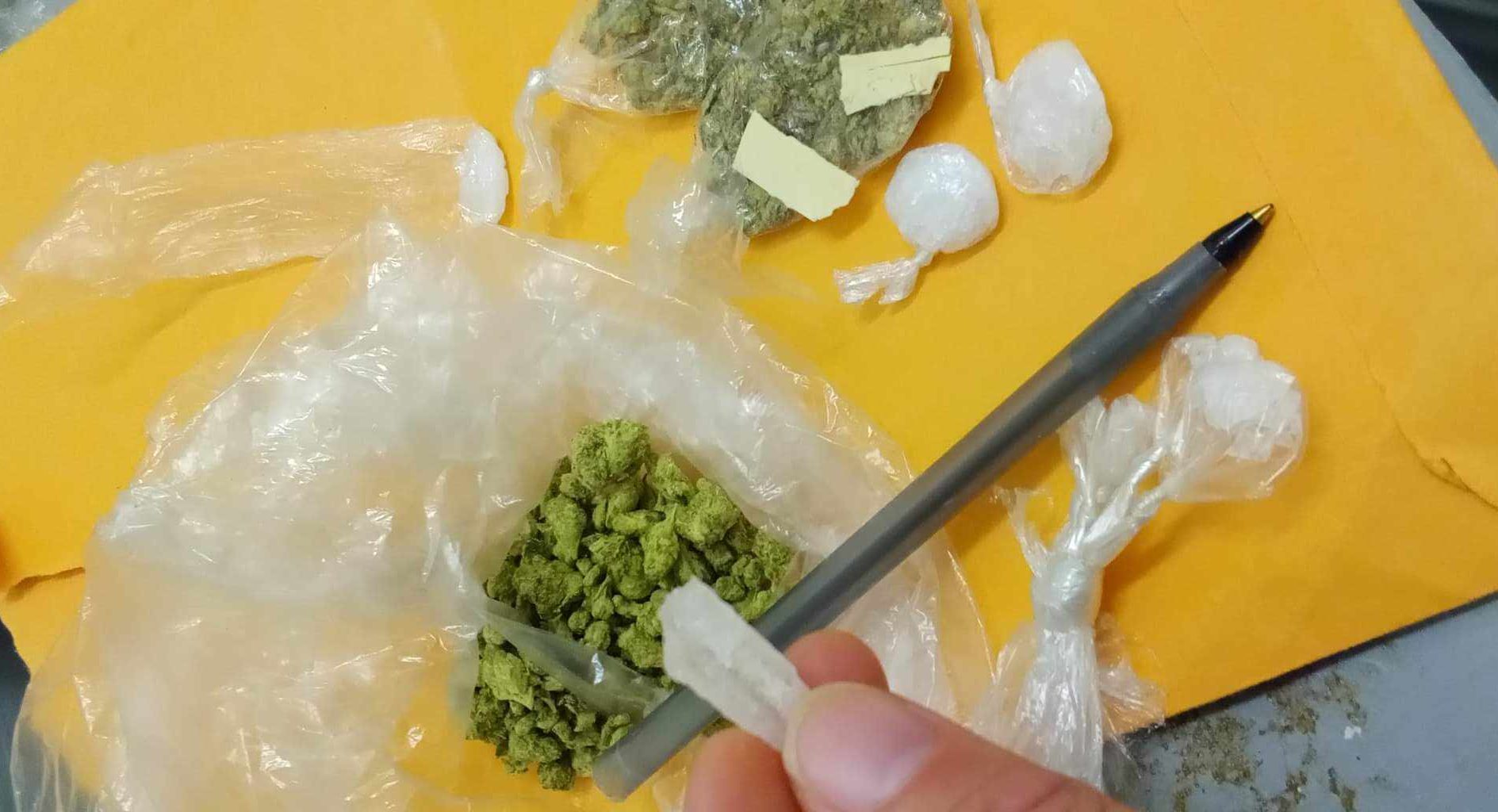

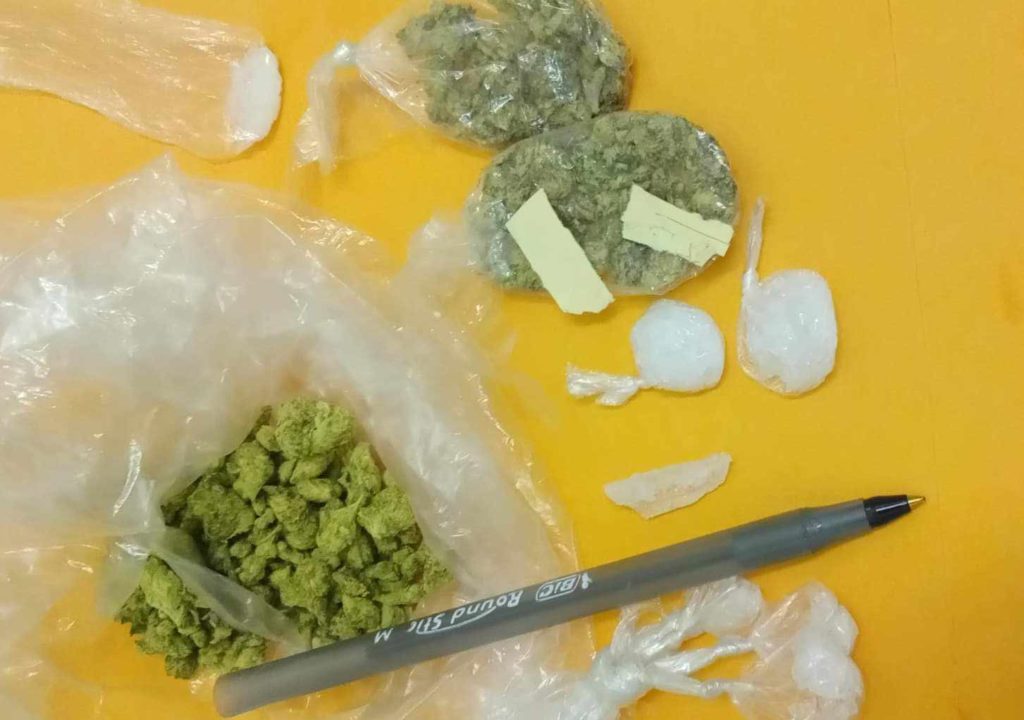

Marijuana, meth and strips (type unknown)

Marijuana, meth and strips (type unknown)

“Available. Cheap. Will Get You High.”

People were using insecticides as a cheap high before 2020, and they aren’t exclusive to Georgia or to prisons. But strips now dominate the GDC supply in a way they never have before, and Raid has emerged as the hallmark. Rabbit saw a sanitation orderly sell a can for $150.

Aerosol chemicals and a strip economy were made for each other. Easy to make; easy to hide; drug dogs aren’t trained to care about insect poison. Spray Raid onto paper—however many coats you want—hang, let dry. Break down into quick hits, sell for maybe 50 cents to $3 each.

“The high is very intense,” Mike, 32, told Filter. “Like a train … just wham, wham.” To a bystander, the effect resembles a seizure—just like a bug when you spray it. Injuries from falling out of bunks are not uncommon.

Raid strips are sometimes passed off as meth or K2, but often advertised truthfully. Strips are also sold simply as strips, and used without discussion of what’s on them.

JD described the results as so unpredictable that if two people smoke the same sheet, in equal amounts, “one may immediately nod off and the other may start barking like a dog.”

People would, of course, prefer to make informed choices about what they put in their bodies. But as in the free world, it’s not always an option, though you could say there’s some regulated supply in the sense that some cleaning products are labeled.

“Since COVID, I have seen Lysol disinfectant wipes smoked,” Rabbit said. “Did they get high? Who knows. Inmate was selling three wipes for $2.”

The most successful strips in JD’s facility seem to be made with “some sort of film developer.” Tyler, 42, saw someone making strips with oven cleaner. This haphazardness makes strips undesirable, but it’s also the core of their appeal.

“It’s available. And it’s cheap. And it will get you high. And it’s available. And it’s cheap,” John said.

Strips are a race to the bottom—which isn’t to say that no one enjoys them—but they’ve also driven up the price of the drugs people were used to. A $5 line of meth, half an inch long and the width of a line you’d draw with a pencil, might now cost up to $25.

“I know they cut it,” Ramis, 33, told Filter. “Sometimes with bath salts [or] sleeping pills.”

A syringe and its hiding place. The owner has had it for two weeks, and expects it to last another two months or so.

Injecting

Syringe service programs (SSP) have been authorized in Georgia since 2019. But this doesn’t apply to the state’s prisons, nor the prisons in the rest of the country.

Most unused syringes come from corrections officers (COs), who can charge $50 for a 10-pack. In one facility, an unused syringe currently costs just $2, or four soups (the prison economy has a currency and exchange rate, the way countries do; GDC facilities are on either the dollar system the soup system, if you don’t count drugs as a sort of third system of its own). In most facilities reached by Filter, an unused syringe goes for $10-$20, and sometimes as much as $50.

“Someone still concerned about living a long time will pay $20,” John said. “But someone who doesn’t care…”

Used syringes are more realistic, hovering around $3 each. They’re often purchased from diabetic prisoners, who pocket them after insulin call. Some end up in the biohazard bins as intended, but they don’t necessarily stay there. Medical orderlies pull them back out to sell.

“They have to leave some in the disposable bucket, to give it the weight and the noise when they’re disposing of it,” John said. “But nobody wants to handle that biohazard stuff, so they’re helping themselves.”

Those who can’t afford to buy, rent. Sometimes the price is a dollar or two; usually just a hit.

“Guy that brings a needle parties for free,” Rabbit said.

The goal is to reuse a syringe as many times as possible.

In the free world, common harm reduction advice is to avoid sharing or reusing needles. Sharing increases risk of transmitting HIV and hepatitis C. Reusing increases risk of abscesses and infection as the needle gets more raggedy; the point starts to dull after just one use. This is why people who use drugs pioneered SSP in the first place.

In prison, where there are no SSP, the goal is to reuse a syringe as many times as possible.

After about a week in circulation, the plunger stops sealing properly because the lubricant has eroded. At this point it’s lubricated with ChapStick, or by sticking it in an ear to get the earwax.

After two weeks, if not sooner, the needle needs sharpening. Finished concrete does the job, so needles are often sharpened on the floor. After that, it’s a matter of how long the thing holds together.

“Six-plus months,” Rabbit said. “Sold, resold … they depreciate with use. But still flushed, sharpened and used. Again and again.”

“Seen dudes use a needle for a year,” Hormiga, 35, told Filter.

“Saw a guy with a needle that looked like it came in from the ’60s,” Mike said. “A syringe will stay in use no matter how ragged it is. Until broken or lost.”

“Until it’s completely broken and irreparable,” JD said.

“You can only sharpen and resharpen one of these things so long,” John said, with a chuckle. “And then it’s over.”

Vapes are sometimes used for meth, marijuana or strips.

Vapes are sometimes used for meth, marijuana or strips.

It is not surprising that in environments where governments prefer that people rent out year-old syringes rather than have access to sterile ones, hep C transmission is disproportionately high. HIV prevalence is elevated as well.

In 2018, Georgia was identified as one of four states without any clear policy for hepatitis C testing and treatment among prisoners. Though only 4 percent were tested, nearly one-third of those tested reactive for hep C.

An HIV testing policy that took effect in February stipulates GDC test new prisoners when they enter the system, and test anyone who’s been in longer than a year before they’re released, but doesn’t include anything about everyone who was already incarcerated, or about connecting people to care.

“I’ve seen some get a medical reprieve because they was dying from hep C, and they was told if they got the cure and survived they would get locked back up to serve their time,” Tony said. He remembers his facility once did annual HIV and hep C tests, but stopped sometime in the mid-2000s; budget cuts.

GDC did not respond to several requests for comment.

“Bleach degrades the plunger, and it needs to last.”

Antiretroviral medications cost tens of thousands of dollars, and a syringe maybe a couple of cents, but GDC won’t fork over either.

Bleach has long been the harm reduction alternative to new syringes when none are available, and it’s the preferred sterilization method here, too. Nearly everyone reached by Filter was knowledgeable about its use—describing variations on drawing it up and squirting it out a few times, then flushing with water—but straight bleach is hard to come by. Some people pay $2 for a soda bottle filled with equal parts bleach and water. Others use whatever it is that the sanitation orderlies dole out first-come, first-serve from a mop bucket.

“I think [COs] know we’re using our dorm chemicals to clean off needles, but I don’t think they care,” Hormiga said. “They’re just not gonna openly endorse that.”

Multiple people, across multiple facilities, were motivated to clean their syringes to avoid hep C—but believed that infection is contracted by re-injecting your own dried blood. You can only get hep C from someone else who already has it, when their blood (dried or otherwise) enters your bloodstream. The prevalence of the same misconception across GDC shows both an opening for harm reduction and an absence of education around it.

Most people don’t want dried blood in their syringe because it clogs the needle. But the inherent predicament of sterilizing syringes in prison is that you can’t afford to do it too often.

“Bleach degrades the plunger,” Tyler said. “And it needs to last.”

“Buck” is wine made from fermented fruit, sugar and yeast. “Clear” is moonshine. Boil buck to cook off the alcohol, cool the vapor in a plastic bag—fast, so it becomes ethanol. Too slow, you get methanol. “If that happens, and you drink it, it can cause blindness,” Tyler said.

Some people make “clear,” or moonshine, though not really for sanitizing purposes. At one time COs would bring in vodka, but they stopped once they realized the real money was in cell phones. These days, any plausible-looking cleaning product will do.

“You get one drop,” John said of squeezing out an alcohol pad. “But that’s plenty!”

Tattoo needles are a separate matter. It’s a common practice for each customer to bring their own needle, ideally a barrel too. To get a new needle, someone has to make it. An open flame is used to heat and straighten out a small piece of wire, like the spring inside a state-issued lock. Artists will often use fire to sterilize the needle before each new tattoo, but the rest of the equipment isn’t as manageable.

Homemade electric tattoo guns are complex compilations of plastic pen casings, eyeglass frames, CD players—all haphazardly sized components that aren’t meant to fit together, which makes disassembling them to clean each part inordinately difficult. Even having more uniformly sized pens would be meaningful hep C harm reduction, since tattoo artists could replace various parts rather than keep reusing them.

Meth pipes, from left: Rabbit; John; unknown

Meth pipes, from left: Rabbit; John; unknown

Alternatives to Injecting

Though the risk is lower than with sharing syringes, sharing pipes and other smoking equipment can still transmit HIV and hep C—especially when people don’t have smoking guards to protect their lips from burns.

SSP will go to some lengths to get glass pipes and stems; COs have no incentive to do this. But many people in prison still prefer to smoke their drugs, particularly meth, and have thus innovated many designs of homemade pipes or “boats.”

The best source for a DIY meth pipes is a glass nitroglycerin pill bottle, the kind prescribed to prisoners with heart conditions. But empty bottles must be returned in order to get a refill.

“If the bottle is scorched in any way, your record is marked, and it’s hell to get your meds,” Rabbit said. “Most people will not risk this for $25.”

Next-best is a small light bulb, like the ones inside smoke detectors or the COs’ little mag lights.

“Every one of them, when they’re new, has a new light bulb in the spring in the base,” John said. “So, ‘Look, I dropped, can I use your light pen?’ And while you’re looking under your bed you take the end off, and you slip the light bulb out, and you put the end back together. Their light works, they’re not missing anything.”

Some people avoid burning their mouths by melting plastic pen casing around the glass to form a smoking guard. Some, like Ramis, find that snorting hits harder anyway. Four people at four different facilities reported that there was at least some degree of booty bumping going on, especially during syringe droughts, but that it was wasn’t exactly something people talked about.

Smoking guards might otherwise be fashioned from rubber bands, but even those can be scarce or expensive. Same with tin foil; people will smoke off it if they can get it, but often substitute with the aluminum from asthma inhalers, or shoeshine canisters.

Meth; marijuana

Supplies R Us

Beyond the drugs themselves, the prison contraband market includes items that in the free world are not only legal, but financially valueless. None of the SSP outreach staples are easy to come by.

Alcohol prep pads, to disinfect skin before injecting, are about six for $1, or 5:1 in the soup economy. Cottons, to filter the dissolved drug being drawn into a syringe, often come from dried-out alcohol pads, recycled after bloodwork or injury. If you want sterile water you can boil it.

Condoms are cling film from sandwiches. Lube is vaseline or mayonnaise or antibiotic ointment. For prisoners who trade sex for drugs, the risk is doubled.

“One guy wanted to use a blue rubber glove, and my stupid ass was like, ‘Uhhh, you’re not sticking that up my ass!'” Rabbit said. “Condoms would be nice if they could be acquired without embarrassment.”

There isn’t much dope inside GDC. Some facilities do have strips purporting to be heroin or fentanyl, but they aren’t that popular. When people say “dope” here, they’re talking about meth. When someone describes an overdose, they’re usually talking about strip-induced episodes that if anything are more like stimulant overamps.

The main opioid in the supply is Suboxone—iconically a strip long before all this. Anyone who tells you Suboxone can’t be injected doesn’t have much experience with prison or people who’ve been there. Suboxone is water-soluble, after all.

All Suboxone here is contraband. GDC doesn’t provide prisoners with medications for opioid use disorder (though one could certainly say Suboxone is provided by staff). Nationally there have been some victories for MOUD access in county jails, but that fight has not made its way here.

Naltrexone and Vivitrol are available in various correctional settings across the country, but methadone and buprenorphine (AKA Suboxone) are not. The moment someone walks out of prison, their overdose risk spikes exponentially; it’s the leading cause of death among people recently released. Tolerance is down, and access is restored. Aside from a 2019 pilot project in which 14 people received Vivitrol injections prior to release, MOUD has not been a priority for GDC.

“We thought, if we supply the spot and let it have clean needles and clean ink, this will be a clean thing.”

In 2001, John and two other tattoo artists had an idea: If they were allowed to buy professional equipment, they could store it securely in a locked office in the gym, then on certain hours set up in one of the craft rooms to tattoo customers there. Beyond being safer for everyone involved, this would allow COs to track and update prisoner files with identifying marks. It almost made too much sense.

“We thought, if we supply the spot and let it have clean needles and clean ink, this will be a clean thing,” he said. “It’s gonna happen—why make it happen less healthy?”

The coach who ran the gym at the time was cool with it, so they drafted a proposal. A fourth prisoner who worked in the library agreed to write it up and give to the warden, who not only said Hell no, but had everyone’s cells shaken down for tattoo equipment.

“So instead, every artist in the system continues using needles made from strands of steel wire, and inks produced painstakingly [from] soot,” John said. “Human beings catch diseases, get sick, some die, all because bureaucrats don’t approve.”

One of the three artists died in prison in 2009; one was released and disappeared into Florida; John continues his life sentence. As far as he knows, no one ever tried to organize around clean needles again.

All photographs anonymous

R Street Institute supported the production of this article through a restricted grant to The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter. Filter‘s Editorial Independence Policy applies.