In 2016, Larry Vessey Jr. was sentenced to 58 months in the custody of Washington State Department of Corrections (WDOC). His second-degree burglary conviction had not involved any drug charges, but because Vessey, 49, had been using methamphetamine for a long time, he was eligible for a drug offender sentencing alternative (DOSA).

DOSA is a program of alternative sentencing handed down by drug courts for people with substance use disorder who are convicted of nonviolent felonies. Eligible prisoners can have their sentences reduced substantially by completing an assigned drug treatment curriculum. In Vessey’s case, DOSA sentencing meant he’d only have to serve 29 months in prison. Then, instead of serving the remaining 29 months in prison, he could be released into community custody, or what WDOC used to call probation.

DOSA sentencing is “designed to provide substance use disorder treatment and community supervision for individuals diagnosed with a substance disorder who have committed a drug or other statutory eligible crimes,” states WDOC’s website. “Individuals sentenced to a DOSA are required to participate in substance use disorder treatment in lieu of prison time.”

Mandatory treatment doesn’t work. Its goal is to stop people from using drugs, and the evidence overwhelmingly shows that the most effective treatment approaches are the ones people choose for themselves. But Vessey’s sentence is the maximum for second-degree burglary, and it had come as a shock. When he got DOSA, he was ready to participate in treatment, whatever that turned out to be.

Twenty-three months passed; still nothing changed.

It didn’t turn out to be anything. Once in prison, he was told that the curriculum didn’t actually begin until the final six months of someone’s sentence, regardless of how much time they’d been given. Twenty-three months passed, and still nothing changed. After 29 months, he was released.

Despite not receiving whatever treatment WDOC considered important enough to reduce his sentence by half, once Vessey was free, he kept his day-to-day life stable. He was meant to be receiving treatment during this time too, but it was three months before he was even contacted for an evaluation. That turned out to be all he was contacted for, but still he went to work in the morning and went home in the evening, and continued to use meth throughout. This lasted about a year.

Drug-testing is a routine part of all supervised release. A couple of Vessey’s urinalysis (UA) tests had come back positive for meth without his community custody officer seeming to care, until one day they did. His DOSA was revoked, and he was taken back to prison to serve the second half of his sentence—sort of.

By now it was 2021, a time when WDOC was releasing some eligible people—not all—early to mitigate COVID transmission. Instead of a regular prison, Vessey was sent straight to work release. This form of partial confinement is normally reserved for prisoners in the final six or 12 months of their sentence. But it seemed that as long as he stayed out of trouble, his 29 months would be cut down to more like four. As he understood it, it was just a brief show they had to put on to punish him for the UA.

Sitting there alone, waiting for what in his mind was a fate that had already been sealed, Vessey panicked.

Vessey began working two jobs. Because he was under constant surveillance, he wasn’t using at all for the first few weeks. Then one day, since he’d been doing so well, he was granted an eight-hour social pass. He left for the day and promptly got high. When he reported back that night, he was immediately drug-tested, then told to wait in his room while WDOC was summoned.

In the context of the COVID releases, there’s a decent chance he’d have still remained at work release. But sitting there alone, waiting for what in his mind was a fate that had already been sealed, he panicked. By the time WDOC officers arrived, Vessey had climbed out the window.

“I would have stayed, and kept both jobs, and worked hard like I was doing,” he told Filter. “But I had a dirty UA. So I just ran.”

After a month as a fugitive, Vessey was picked up and sentenced to an additional two years on top of the five he was already serving. But the same COVID precautions were still in place. Vessey recalls being told that if he stayed out of trouble for a couple of months, until he got a bit closer to his release date, he’d be sent to graduated re-entry (GRE)—home confinement, once he had a home in which to be confined.

He submitted the address of his family home. It was denied, apparently because the home contained a gun safe, even though according to Vessey his family had emptied it in preparation for his arrival. WDOC told Filter that an empty gun safe would not be disqualifying.

Vessey didn’t have a backup address. After a few more weeks in prison, he submitted the address of woman who’d contacted him over JPay because she was looking for prisoners to write to. They’d only been exchanging emails for a few weeks, and had never met. But she said she had a house, and he should come live there.

“There was no preparation for the GRE,” Vessey said. “When [the] address was approved I was out in days.” He did the terms-and-conditions paperwork in the back of the cop car on the way over.

“They required me to be abstinent … but then the only address they would let me go to was a drug den.”

According to Vessey, when WDOC was dropping him off there were used syringes in plain view on all surfaces of the home. The officers drove away.

“Syringes in plain view is not always a sign of illicit drug use, as there could be medical needs that are in play,” WDOC stated in response. “However, if syringes were in plain view, it would at least prompt an inquiry by the investigating officer as to the reason.”

The way Vessey tells it, the woman who answered the door had a thin trickle of blood running down her neck from having just shot up.

“They required me to be abstinent … but then the only address they would let me go to was a drug den,” Vessey said. “And then they didn’t even help me stay clean.”

Vessey knew he couldn’t stay at that address if he wanted any chance at staying sober. After repeatedly complaining to GRE officials, he was assigned a bed in a sober living facility, which turned out to contain more drugs than the “drug den.”

GRE also required Vessey to participate in treatment. This consisted of one Zoom counseling session per week. None of it was drug-specific, just the same boilerplate 12-step rhetoric for everyone regardless of why they were there. Vessey didn’t find this particularly useful, but he participated nonetheless.

He also became intimately involved with his counselor, who told him he didn’t have to keep signing onto the Zoom; she’d just pass him. Some months later they broke up. Though the meth-positive UA he received around this time was not his second, it was the second to send him back to prison. Officers don’t care about UA until they do.

In February 2021, State v. Blake struck down felony drug possession in Washington, reclassifying it as a misdemeanor. Hundreds of people incarcerated in state prisons for felony possession became eligible for a commutation order, and though not all of them received it promptly, some did. Still more were freed from county jails and from community supervision. Vessey is not eligible for commutation—there’s nothing drug-related on his record.

In the eight years since Vessey began his five-year sentence, the only criminal charge he’s incurred is escape in the first degree. The reason he keeps getting sent back to prison is UA. He’ll be the first to tell you that climbing out the window wasn’t his most rational decision, but UA was the reason for that, too.

People who believe drug use should be criminalized will of course say that Vessey is sitting in prison today because he chose to use drugs, not because WDOC chose to test him. But WDOC has also placed him in drug-treatment programs where he received no drug treatment, denied his request to live with his non drug-using family and approved his request to live with drug-using strangers.

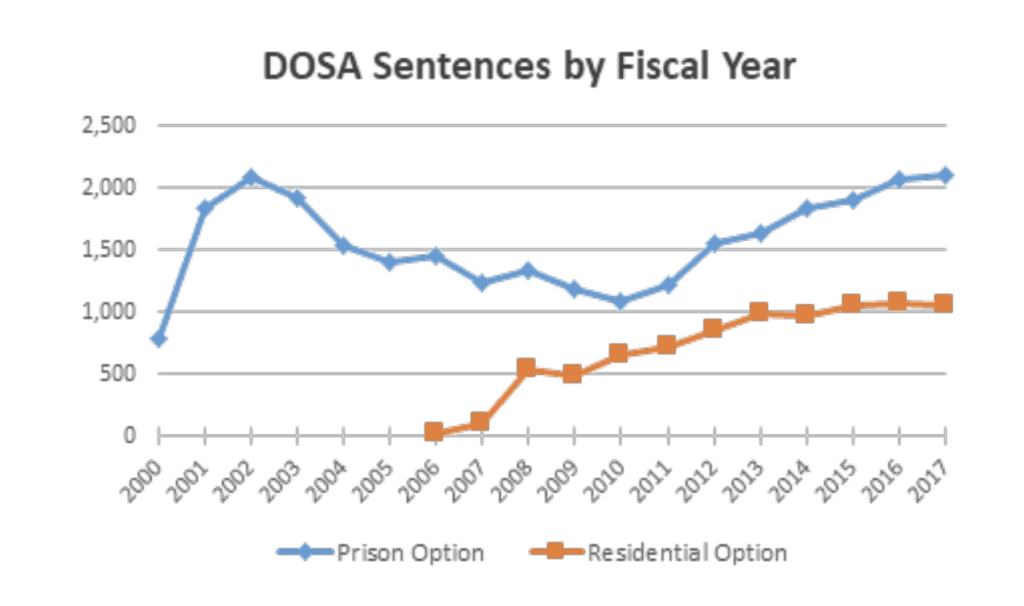

The stated goal of DOSA, and of drug courts in general, is “to reduce or eliminate confinement time.” Per WDOC data, nearly half of all people who receive this sentence ultimately have it revoked. Like Vessey, many people are sentenced to drug treatment despite not being convicted of any drug-related charges, only to end up with longer sentences than they initially received.

Vessey has about four months left on his sentence. Once released, he’ll no longer be under community supervision. No more UA; free to use meth if he chooses. He feels uneasy, not about the effect meth will have on him if he uses it, but about the effect the criminal legal system will have on him if uses it.

The harm Vessey wants desperately to reduce isn’t really from meth; it’s from the criminalization of meth and the activities that go into acquiring it. When he’s not being drug-tested, he does just fine.

As he described what he meant by wanting to stabilize, it put me in mind of medications for opioid use disorder, like Suboxone. I asked him if he knew about those.

“I do! I wish I could get something like that for meth,” he said. “I see those other guys get their stuff together all the time.”

Read Part 2 of this story here

Top photograph via Council of Accountability Court Judges of Georgia. Inset image via Washington State Department of Corrections.