We are in the midst of what has been dubbed a “postal service crisis.” And although the potential impact on the presidential election has dominated headlines, that isn’t the whole story. The elimination of overtime for mail carriers, reduction of post office hours and removal of postal boxes not only threaten every citizen’s ability to send and receive mail in a timely fashion, but also the lives of people who use drugs.

How? By further limiting—particularly during the pandemic—access to the lifesaving medication naloxone (Narcan) that reverses the effects of opioids during an overdose.

People have long depended on the postal service for routine medications to treat illnesses like diabetes and hypertension. Now, many individuals are forced to wait two weeks for diabetes medication that used to arrive in three days. People who need naloxone and are no different—their lives and the lives of those they love are at risk when they lose access to this medication.

Longstanding barriers to naloxone access are compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, making mailing programs more important than ever.

Thanks to an innovative partnership between the Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH), NEXT Naloxone and SOL Collective, Philadelphians can now receive free naloxone via mail. Mailing eliminates many barriers to access, but this approach depends on fast mail service to meet the urgent need.

Longstanding barriers to naloxone access are compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, making mailing programs—which also exist in many other parts of the US, thanks to NEXT Naloxone—more important than ever before.

Stigma—often experienced by people who use drugs and their families—can prevent people from presenting to their local pharmacy to get naloxone, despite its availability. Asking for and receiving naloxone can be socially challenging at the best of times.

Naloxone can also be costly—especially for those without health insurance. As millions of Americans have lost work (and work-sponsored health insurance) due to the pandemic, paying for naloxone presents another barrier to those who need this lifesaving medication. For uninsured people, a box containing two doses of naloxone nasal spray formulation (Narcan) can cost between $130-200.

As Pennsylvanians are told to stay home and limit physical interactions to avoid exposure to coronavirus, people may also avoid pharmacies even if they need lifesaving medications. While Pennsylvania’s standing order allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone to anyone without a prescription, this order is ineffective if people cannot physically present to pharmacies or afford the medication once they get there.

Thankfully, following long-term advocacy from the harm reduction community, Governor Tom Wolf and Secretary of Health Dr. Rachel Levine recently signed an updated standing order officially allowing for naloxone delivery by mail.

However, as USPS services are delayed and mail carriers are struggling to deliver necessary goods, this standing order may unfortunately be less effective than imagined. The impact may be especially severe in rural Pennsylvania communities that lack the in-person harm reduction resources of cities like Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

While the postal crisis could have a severe impact on naloxone access, that is far from its only potential harm to drug users’ health.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the drug supply in Philadelphia and elsewhere even more dangerously unpredictable, although fentanyl was already extremely prevalent. Supply chain disruptions mean that not only heroin, but also drugs like cocaine and MDMA are more likely to be laced with cheaper, more powerful adulterants, increasing the risk of overdose and death.

While the postal crisis could have a severe impact on naloxone access, that is far from its only potential harm to drug users’ health. Many people who use drugs rely on the mail to deliver a range of safer-use supplies—including, for example, fentanyl test strips. And some find that purchasing drugs from online marketplaces—which are then delivered by mail—presents fewer risks than buying on the street.

Pending federal lawsuits may have temporarily stalled the Trump administration’s efforts to limit the postal service’s reach until the presidential election, but the opioid-involved overdose crisis will extend well beyond November 3.

For the health of our democracy, of the wider public and of people who use drugs, a properly supported, fully functioning postal service is essential.

This article was co-authored by Rebecca Hosey, Billy Ray Boyer and Shoshana Aronowitz.

Rebecca Hosey, MPH works as a public health consultant and case manager for Prevention Point Philadelphia, while attending nursing school at University of Pennsylvania. She lives in Philadelphia.

Rebecca Hosey, MPH works as a public health consultant and case manager for Prevention Point Philadelphia, while attending nursing school at University of Pennsylvania. She lives in Philadelphia.

Billy Ray Boyer is an abolitionist harm reductionist, recovery specialist and community organizer with SOL Collective. They live in Philadelphia.

Billy Ray Boyer is an abolitionist harm reductionist, recovery specialist and community organizer with SOL Collective. They live in Philadelphia.

Shoshana Aronowitz PhD CRNP is a family nurse practitioner, community organizer with SOL Collective and University of Pennsylvania National Clinician Scholars Program fellow. She lives in Philadelphia.

Shoshana Aronowitz PhD CRNP is a family nurse practitioner, community organizer with SOL Collective and University of Pennsylvania National Clinician Scholars Program fellow. She lives in Philadelphia.

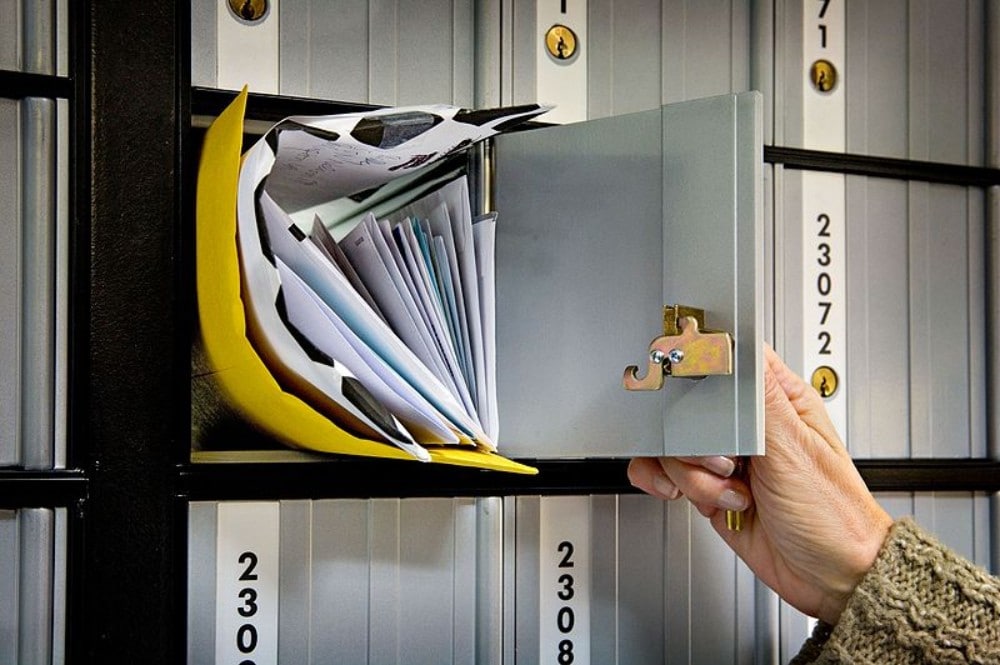

Top photograph by United States Postal Service via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 3.0

Show Comments