Unless they’re serving life, most parole hopefuls in Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) custody become statutorily eligible for release after they’ve served one-third of their sentence. If the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles decides that the person does indeed deserve parole, they’ll assign a Tentative Parole Month (TPM).

So if someone coming into GDC on a 10-year sentence gets the earliest conceivable TPM, they’re looking at a minimum three years, four months in prison before they might be released to serve the remaining six years, eight months on parole. This does not mean that they’ll be granted parole at that time, or at all. It simply means that they will spend at least the next three years, four months in prison, and after that they can hope.

In 2015, GDC introduced the Performance Incentive Credit (PIC) program. PIC falls in the carrot-on-stick genre of prison sentencing reduction known variously as Good Time or Earned Time. By participating in PIC-eligible activities, PIC-eligible prisoners can earn up to 12 PIC points. Each point credited equals one month knocked off your TPM.

In theory, PIC is both an incentive for prisoners to work as hard as possible and a decarceration tool that advances them into parole. In practice, it is neither. It is a source of false hope without any accountability or oversight mechanisms, in the long GDC tradition of giving us things to hope for that way.

GDC re-entry case plans have six categories: Substance Abuse, Cognitive Behavioral, Education, Vocational, Mental Health and Sex Offender. If you finish every activity in a given category, you get one PIC point.

You can also earn up to six points through additional PIC-eligible educational or vocational programing, and up to six through PIC-eligible work assignments (one PIC point in your first year on the job, then another every six months with satisfactory performance). But no matter how many classes you take or hours you work, you can still only be awarded a maximum of 12 points.

If you keep your nose to the grindstone, you can finish 12 points’ worth of activities in under two years. Which is why prisoners learn not to pursue PIC at the beginning of their sentence. Points, as they accumulate, become something to lose. The stress of any infraction, whether issued to you personally or to the cell block en masse, being used to wipe away your points is best not dragged out any longer than it has to be.

“PIC wasn’t ever good towards rehabilitation,” Wallace* told Filter. “The sole purpose was a means of control, and that failed from the start.”

For many in GDC custody, PIC is a moot point from the beginning due to various disqualifying elements of their sentence. Wallace, myself and others sentenced to life with parole have a TPM of “Life,” and the Board doesn’t have to do much but think of us from time to time.

“What’s that? Oh, the bullshit about earning a month per [point],” Willie*, who is currently incarcerated on a 30-year sentence and not eligible for a TPM, told Filter when asked about PIC. “To do what with? Pay an extra month of parole fees is what.”

Some do the work, but have the evidence wiped from their record by GDC before the Board ever reviews it. Some have the evidence submitted to the Board in pristine condition, only for the Board to decide not to award the points anyway. Some are awarded the points, have their TPM advanced accordingly, and end up where so many of us do anyway—still in prison, regardless of whatever paperwork says we don’t have to be.

“The cut is not promised. It is just a suggestion. A recommendation from the Department of Corrections to the Pardons and Parole Board,” Charles*, who is incarcerated on a 25-year sentence and also not eligible for a TPM, told Filter. Though GDC “promises to rescind the recommendation if the prisoner ever misbehaves.”

After the GDC staff exodus of 2020, a lot of the PIC classes and groups no longer had anyone to run them. But poor attendance doesn’t just reflect on the prisoners; it also makes GDC case workers look bad to their boss, who in turn looks bad to their boss, and so forth.

“Many of the post-pandemic classes only existed on the schedules,” Bill*, whose TPM is in 2024, told Filter. “No one was expected to actually show up. But the records had to show a ‘by the book’ record.”

In 2022, after Bill and another prisoner were assigned as general duty aides in the education area, two GDC case workers began asking them to help catch up on some work.

“It would be awkward to refuse,” Bill said. “So of course we did as asked.”

On Fridays, when the regular hard-nose CO was off-duty, one of the counselors would sit at his desktop and pull up the group attendance records for classes like “Moral Recognition Therapy” or “Thinking For Change.” Then he’d go off to the chapel for his morning class and leave Bill to “click the boxes.”

Bill would cross-reference the classes’ group roll with the facility’s lockdown roll, noting who was in the hole or away for court or medical. Then for every prisoner on the counselor’s case load who would have been physically able to attend, he’d mark them as having attended. If he heard one of the deputy wardens coming to make rounds, he’d turn off the monitor but not the computer, and simply pretend to be emptying the trash for a moment.

“The guy who worked with me [as an aide] did the same for the other counselor. It was a regular thing,” Bill said. “Some weeks I would go ahead and mark [everyone] as Present [for] the month’s remaining classes, because I was going to be busy myself.”

This happened Friday mornings three times a month for a year. In 2023 Bill was assigned to a new area, but feels certain that his replacement was soon doing the same thing. GDC did not respond to Filter‘s request for comment.

Staff have always delegated their workload to prisoners. This ranges from menial tasks—updating phone lists and visitor lists; helping with the mail—to more substantive ones like creating lesson plans. Though the computer aspect was new.

Of course, perfect attendance by every prisoner at every class must look a bit suspicious after a while. Many prisoners are now convinced that not only is the Board aware of what’s going on, but uses it as internal justification to deny crediting the points.

“The Board has not changed its process of reviewing and considering PIC,” Steve Hayes, director of communications for the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles, told Filter. “A majority of all PIC earned by offenders is awarded by the Board, in excess of 80 percent.”

It’s hard not to speculate, because though the Board purports to have an “evidence-based, scientific and data-driven” decision-making process for all things parole-related, they don’t tell anyone what it is. None of us has really been able to predict who gets out and when. Some people whose PIC points are credited do actually get out on their new TPM. This has, by all appearances, seemed random.

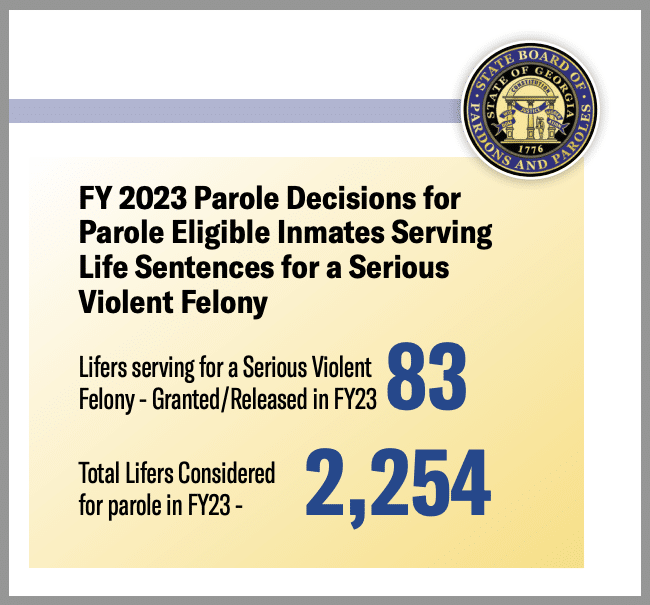

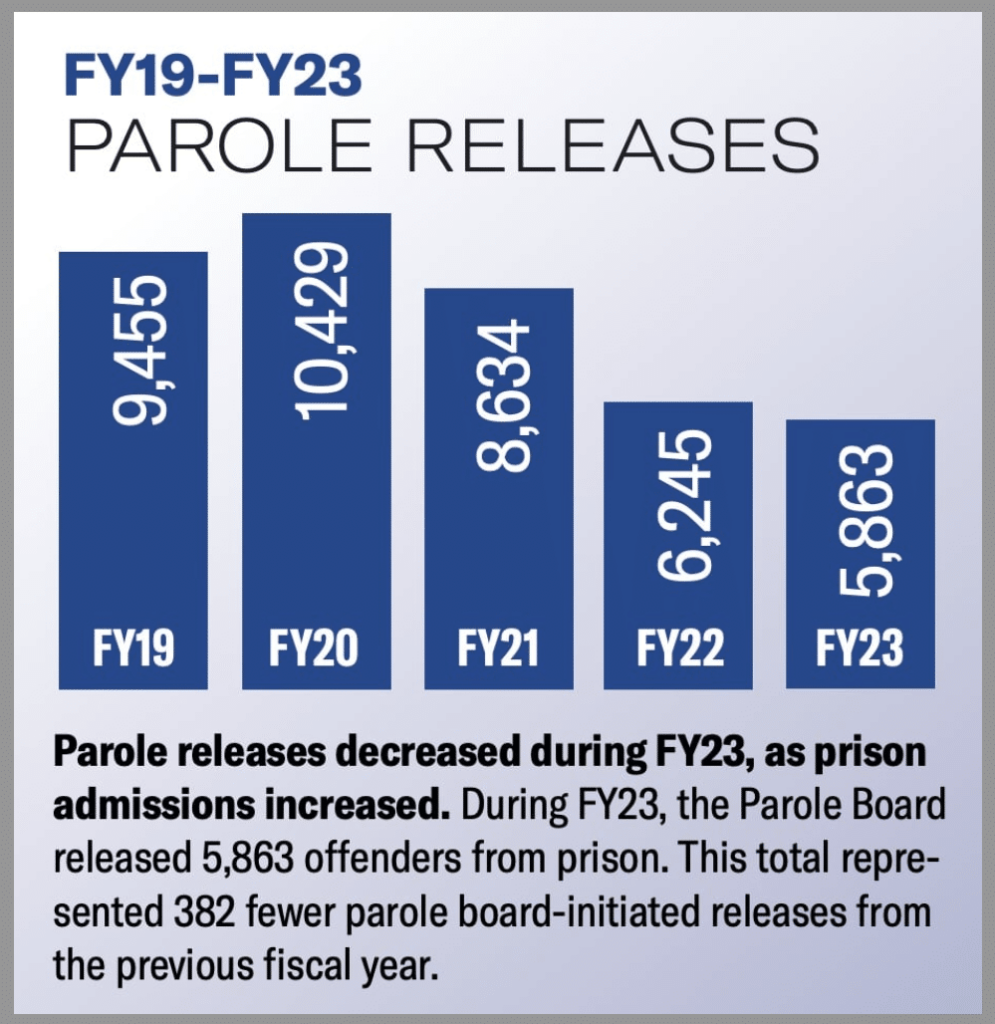

In 2023, the Board granted a total of 26,855 PIC points to GDC prisoners, whose TPM were bumped up accordingly. This has not amounted to more people getting out sooner. In 2020, a brief pandemic-era swell brought the number of people released on parole from 9,455 up to 10,429. It has dropped each year since, with only 5,863 people let out in 2023.

The original three-person Board was formed 80 years ago, when the number of people incarcerated in Georgia prisons was hovering in the 3,000s. Fifty years ago, to keep up with a prison population that has swelled to over 9,000, the Board was expanded from three members to five. Today, GDC incarcerates over 49,000 people, and the Board still has five members.

In 2023, they were sent more than 17,000 cases for review, each of which has additional elements to vote on besides just whether or not to let someone out. Per some back-of-envelope math, each day they went to work each Board member would have had to cast more than 50 separate votes. In the absence of any clues as to how the process actually works, we tend to picture someone over there clicking boxes, too.

*Names have been changed for sources’ protection

Top photograph via Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles. First inset graphic via Floyd County, Georgia. Second and third inset graphics via Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles.