Stigma is a powerful force working against the health and safety of people who use drugs. It reduces medical care quality, dissuades people from seeking help and resources, pervades interactions with police, and haunts even people who quit drugs. Harm reductionists are intimately familiar with these issues and have worked hard to decrease stigma. But have public attitudes caught up?

My recent study, published in the journal Social Science & Medicine, surveyed over 1,400 people’s attitudes about fentanyl-involved overdose victims. The results show that the public is far from embracing a harm reduction perspective.

Social science researchers have conducted public opinion surveys and experiments for decades, in hopes of better understanding substance-use stigma. However, as a sociologist and harm reduction activist, I noticed that most of these studies share a common weakness: They only focus on stigma against people with substance use disorders (SUD). The large majority of people who use drugs (PWUD) do not experience SUD, yet researchers have largely neglected to study how stigma impacts them.

To gain a more inclusive understanding of stigma against PWUD, I designed an experiment in which 1,432 adults in the United States read and responded to fentanyl-involved overdose obituaries.

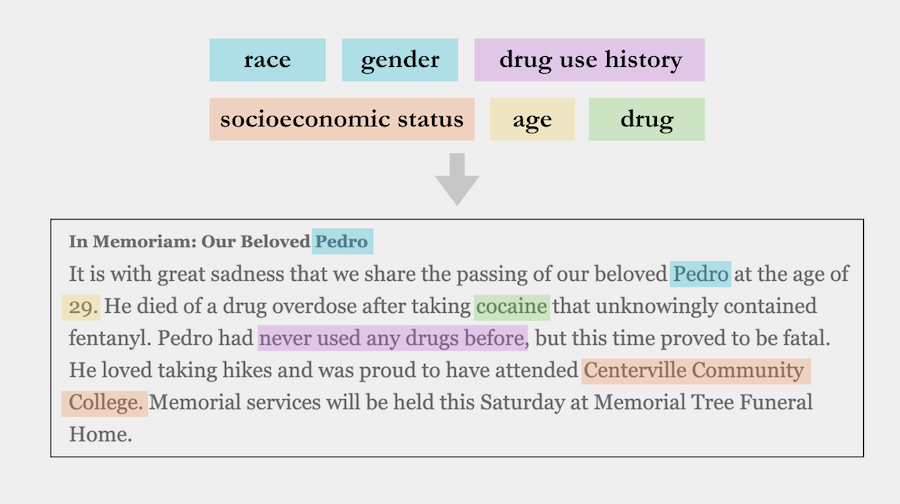

I varied key details including the victim’s race, gender, age, socioeconomic status and drug-use history, as well as the drug they intended to use.

Although these obituaries were fictional, they were written to mimic the structure and content of the overdose obituaries that we often encounter in the real world. By focusing on overdose victims, my experiment included more variation in individuals’ histories, better reflecting the full population of people who experience substance-use stigma.

In each obituary, I randomly varied a few key details, including the victim’s race, gender, age, socioeconomic status and drug-use history, as well as the drug they intended to use. In one obituary, the victim might have been portrayed as a white man who had used drugs a handful of times before; in another, she might have been an Asian American woman with SUD.

Most of these details were stated explicitly, but to keep it feeling natural, I selected names that have been shown to convey a particular race and gender, a common trick in social science experiments. Likewise, I used college attendance at a community college, state school or Ivy League university to hint at socioeconomic status.

Other than these small identifying changes, everything else about the obituaries was the same. This design sought to reveal how tweaking different factors would alter the public’s response to a person’s story.

A sample obituary from the study shows where selected traits were inserted.

After reading two of these randomly generated obituaries side-by-side, respondents were asked which person’s overdose was “more likely caused by their own choices.”

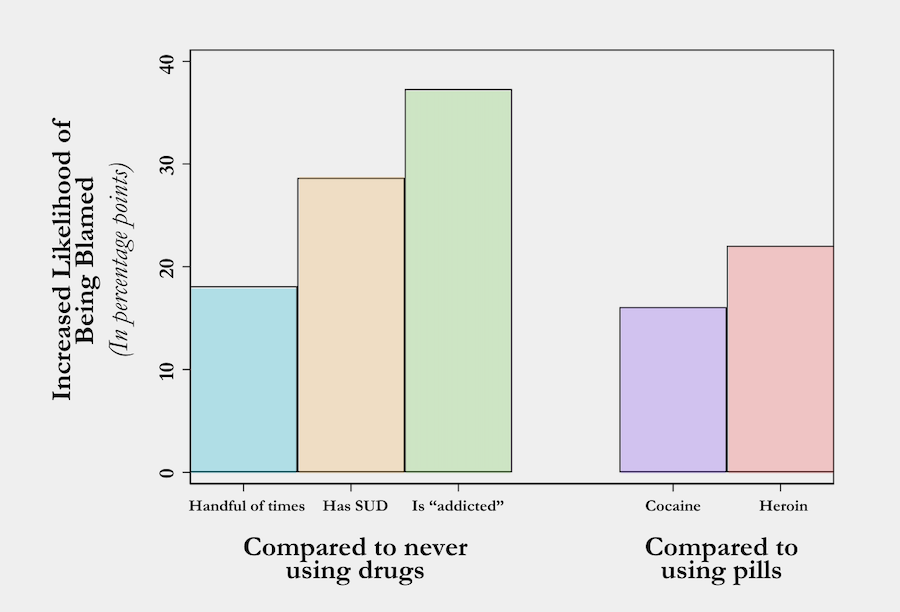

Two traits emerged as the most influential in determining blame: which drug a person was intending to use, and how long they had been using drugs.

I then asked participants, in an open-ended question, to explain how they decided which victim was more to blame, providing a window into their underlying attitudes, beliefs and prejudices. This question provided a chance for participants to state if they did not believe that either person was to blame (in the previous question, “neither” was not an option).

Out of all six traits that I randomly varied, two emerged as the most influential factors in determining blame: which drug a person was intending to use, and how long they had been using drugs.

People who intended to use heroin were judged most harshly out of the available options, followed by cocaine. Compared to people who intended to use prescription pain pills, people who used cocaine and heroin were 16 and 22 percentage points, respectively, more likely to be selected as more to blame. (Pre-testing revealed that the public knew little about other drug possibilities, or intentional fentanyl use, which was why I stuck with these limited scenarios.)

Similarly, the longer someone had been using drugs, the more likely they were to be blamed for an overdose. People who had used drugs even “a handful of times before” were 18 percentage points more likely to be blamed than those who had never used drugs prior to the overdose event.

Chart shows which characteristics made victims more likely to be blamed for their overdose.

Identity-based characteristics like race, socioeconomic status and gender held far less sway—and in most cases, no detectable impact—in determining how people assigned blame to overdose victims, according to my results.

The one identity-based characteristic that did consistently matter was age, which survey respondents often interpreted as a good measure of whether someone had enough “life experience” to have “known better.”

Only a small sliver of participants used the open-ended response to affirm that no one is more to blame than anyone else.

As one respondent noted when asked to justify her decision, “[The person I chose to blame] was quite older, and had much more experience in life. She was also a prior drug user, and should have realized better than [the other victim] the chance that her drugs might be laced with fentanyl.”

The vast majority of open-ended responses (83 percent) followed a similar format; respondents tended to highlight one or two specific traits and explain why those details made one victim more responsible than another. Only a small sliver of participants—around 13 percent—used the open-ended response to affirm that no one is more to blame than anyone else.

What do these results mean?

On the one hand, they’re a promising indicator that prejudice based on identity traits like race, class, and gender might be declining. However, it is possible that this could be explained by social desirability bias—a phenomenon where participants try to conceal their prejudices so they don’t feel judged by researchers.

But even if this were the case, it would show that participants—who instead openly justified their decisions based on what they viewed as personal choices—don’t see a problem with sharing their stigmatizing beliefs about PWUD. It demonstrates just how powerful and ubiquitous these “personal choice” narratives have become.

Victims described as having experienced addiction were more likely to be blamed than those who’d experienced substance use disorder.

Harm reductionists have put enormous effort into explaining why people use drugs, and into reframing SUD as a treatable condition rather than a personal failing. Yet these results indicate that many people still think about substance use—including use that wouldn’t meet SUD criteria—as a morally damning decision.

My study also demonstrates—yet again—the importance of language. Victims who were described as having experienced addiction for many years were more likely to be blamed than those who’d experienced substance use disorder for many years, when all other details were identical. People with SUD were 28 percentage points more likely than first-time users to be blamed; people described as “addicted” were 37 percentage points more likely.

While it may be tiring to police how people speak about these issues, especially in light of pushback against “woke” terminology, these findings and others provide a compelling reminder that how we describe substance use heavily impacts how PWUD are perceived.

Of course, it takes more than affirming language and positive media representation to produce a real change in attitudes. Even after reading humanizing obituaries that focused on overdose victims’ educational achievements, hobbies, and how much they were loved by friends and family, many participants in the study still lacked sympathy. This research underscores the importance of finding creative new strategies for reducing stigma and promoting empathy for all people who use drugs.

Top photograph of obituary notices in Bulgaria by Edal Anton Lefterov via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 3.0. Inset graphics courtesy of Sydney Sauer.

Anyone who wishes to read the full study but cannot access it due to a paywall is welcome to email sydneysauer@fas.harvard.edu for a copy.