Roughly 66 times every single day in British Columbia, someone calls 911 for a suspected drug overdose.

And 66 times every day, an operator answers one of those calls, assesses the situation, and dispatches firefighters or paramedics (not police).

And then those professionals rush out and, nearly 66 times every single day, they save a person’s life.

“When BCEHS [BC Emergency Health Services] paramedics respond to a potential overdose patient, the patient has a 99 percent chance of survival,” reads an email from Shannon Miller, a spokesperson for the agency.

As a Vancouver-based journalist covering drug policy, one of the most common questions I’m asked is this: If Vancouver is so great with harm reduction, why are overdose numbers there so high? An analysis of relevant data can help explain.

With a population roughly the size of Colorado’s or less than half the size of Pennsylvania’s, there aren’t actually all that many people in BC. And yet Canada’s westernmost province is the epicenter of the country’s overdose crisis.

“The provincial rate of paramedic attended overdoses events (events per 100,000 BC residents) has increased 4 fold in less than three years, from 8 events/100,000 in January 2015 to almost 31 events/100,000 by March 2019,” reads a BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) summary of the situation. “While the rate of events has steadied in late 2018, March 2019 saw the highest rate ever at 31 events/100,000.”

These are war-zone figures. And, more than five years after the synthetic opioid fentanyl arrived in the heroin supply and BC’s overdose crisis began, they are still only getting worse.

Last year, BC first responders answered more 911 calls for drug overdoses than ever before, according to new data that BCEHS has shared with Filter. There were 24,166 emergency calls for overdoses across the province in 2019.

That’s up roughly two percent from 23,662 calls in 2018 and 23,441 in 2017—and way, way up from 12,263 calls just four years ago, in 2015—according to additional statistics supplied by BCEHS.

“For the last three years the total number of overdose calls paramedics attend has remained steady–but this steady volume of overdose calls (now, more than 24,000 calls a year) is double what it was before the overdose crisis began,” a January 9 BCEHS statement reads.

Meanwhile, the number of fatal overdoses BC suffered in 2019 actually declined and, remarkably, declined by a lot.

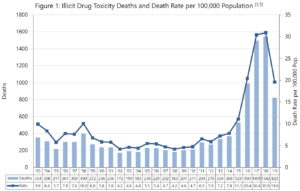

There were 823 illicit-drug overdose deaths recorded by the BC Coroners Service (BCCS) during the first 10 months of 2019. That puts the province on track for a projected 988 deaths last year.

That’s down from 1,542 fatal overdoses in 2018 and 1,495 in 2017.

Graph showing illicit drug-involved death rates in British Columbia from 1993-2019. Credit: BC Coroners Service.

However, while a one-third decline in overdose deaths is good news, it comes with a major caveat.

Nearly a thousand deaths last year is a number that remains miles above what was once considered “normal” in BC. Five years ago, in 2014, BC recorded just 369 fatal overdoses.

From 2001 to 2010, the average number of deaths each year was just 204, barely one-fifth the “good news” number of 988 projected for 2019.

Overdose deaths are down, but overdoses are not. They are higher than ever before. What, then, accounts for the decline in the ratio of overdoses that turn to fatal overdoses?

“Without access to and rapid scale-up of harm reduction and treatment strategies, the number of overdose deaths in BC would be 2.5 times as high.”

BC authorities’ response to the opioid epidemic has primarily consisted of programs and services that fall under the umbrella of harm reduction—a field of health care that seeks to minimize the harms of drug use without necessarily eliminating the use of drugs itself.

The BCCDC has flooded the streets of neighbourhoods acutely affected by the crisis with the overdose-reversal drug naloxone. It’s made it free and widely available without a prescription and offers regular training sessions in overdose response that anyone can drop in to attend, also free of charge.

Regional health authorities have opened additional supervised-injection facilities (SIF) and established a new category of low-threshold supervised injection called overdose-prevention sites (OPS).

Still more de facto supervised-injection sites have been integrated into dozens of supportive-housing buildings in BC operated by nonprofit government partners.

Activist organizations like the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) responded to the onset of the overdose crisis by forming teams of volunteers trained in overdose response and sending them out to patrol the alleys of the city’s downtown core. Inside private single-room occupancy hotels (SROs), marginalized citizens have organized amongst themselves to ensure naloxone is available within their buildings, and that as many residents as possible know how to use it.

Along back alleys in impoverished Vancouver neighbourhoods like the Downtown Eastside, it’s not uncommon to find naloxone kits clipped to chain-link fencing, left hanging there by persons or groups unknown, for anyone who might one night use it to save a friend’s life.

BC, and especially the city of Vancouver, continue to see an unprecedented number of 911 calls for drug overdoses. But, while authorities have failed to slow the number of overdoses occurring, they have begun to slow the number of those overdoses that end with a death.

“The rapid expansion of harm-reduction services in response to BC’s overdose crisis prevented more than 3,000 possible overdose deaths during a 20-month period,” reads a June 2019 media release summarizing a paper co-authored by the BCCDC’s medical lead for harm reduction, Dr. Jane Buxton.

During the period analyzed—April 2016 to December 2017—there were 2,177 illicit drug overdose deaths in BC, according to the BCCDC paper. “The study estimates that without access to and rapid scale-up of harm reduction and treatment strategies, the number of overdose deaths in BC would be 2.5 times as high,” it reads.

Rates for overdose deaths in Vancouver and across BC remain the highest in Canada. But without harm reduction, they would be far worse. And harm reduction may now be beginning to turn the tide.

Photo of naloxone kit hanging on Downtown Eastside fence in Vancouver by Travis Lupick.

Show Comments