Opvee, an opioid-overdose antidote manufactured by Indivior that was approved in 2023, has in recent weeks been slowly rolling out to law enforcement departments. Unlike Narcan or other overdose antidotes currently on the market, Opvee isn’t a naloxone product. It’s nalmefene, a different opioid antagonist that lasts longer. According to cops, nalmefene works better on fentanyl— despite the fact that it’s never been tested in real-world settings, and naloxone still working just fine.

Indivior is positioning Opvee as the “first and only overdose rescue medicine approved to reverse overdoses caused by synthetic opioids” like fentanyl, in addition to plant-based opioids like heroin. Naloxone products don’t specify this, which makes sense because opioid antagonists work on synthetic opioids in exactly the same way they work on plant-based ones. Indivior did not respond to Filter‘s inquiries.

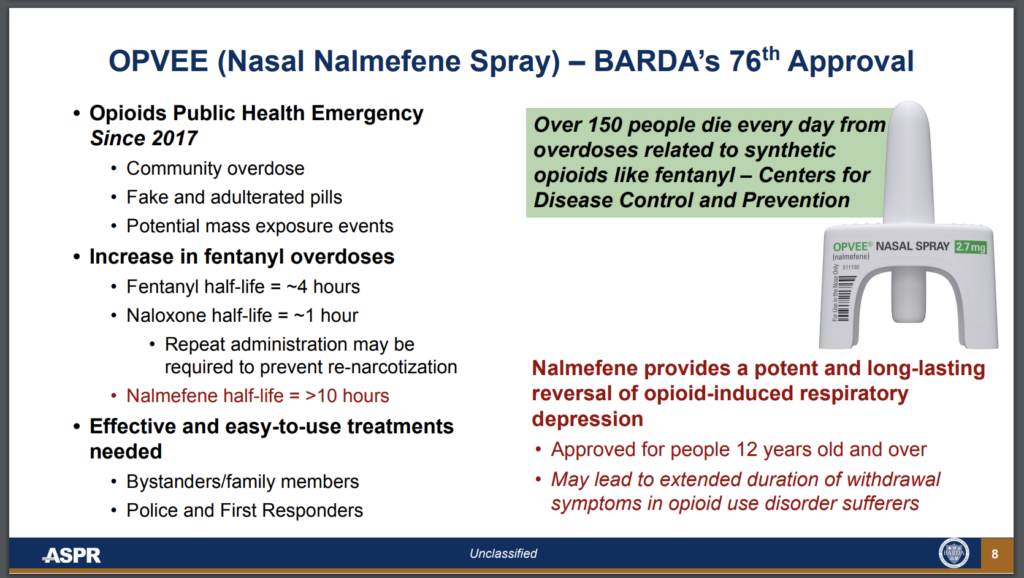

Proponents of Opvee claim that naloxone isn’t strong enough for fentanyl, and that’s why you have to use so many doses. Usually they’ll say something about how naloxone only has a half-life of about two hours, and fentanyl’s half life is up to seven hours, and that’s why you can die from what’s still in your system once the naloxone wears off. Then how nalmefene works faster and has a half-life of 11 hours, and that’s why it’s at least as good as naloxone, if not better.

Fentanyl’s half-life is actually about the same as that of heroin or morphine, but the length of time it technically remains in your body isn’t the thing that matters here. An opioid’s half-life might matter for urinalysis testing, but in this context it’s just something that sounds science-y without actually meaning anything.

Opioids with comparable half-lives are still absorbed by the human body at very different rates, so the effects wear off at different rates. Morphine affects you for longer than heroin. Heroin affects you for longer than fentanyl. Fentanyl is known for being a short-acting opioid, meaning the effects peak early and wear off long before it’s out of your system. (The study Indivior is leaning on used remifentanil, an “ultra short-acting opioid.”)

Now that Narcan is no longer a prescription medication, states no longer need the standing orders that once authorized pharmacies to sell Narcan to people without a prescription. At least 25 states, however, now have standing orders in place for Opvee. Sources familiar with the situation told Filter that Indivior has aggressively lobbied for its product to be included, to the point of intimating legal action.

Drug war propaganda is always easy to get away with, since there’s no adequate public education about drugs to correct it. But there is something especially sad about seeing an entire marketing campaign built around the idea that fentanyl is a long-acting opioid.

The fact that fentanyl is a much shorter-acting opioid than heroin means that people using it on a regular basis get sick a lot faster, so they need to buy and use more frequently, which leaves them significantly more vulnerable to both overdose and incarceration, and just makes life harder in general.

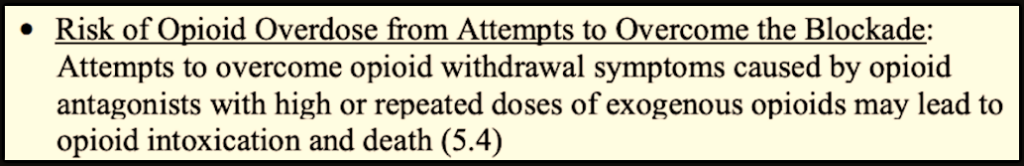

Much of Opvee’s FDA labeling is the same as Narcan’s verbatim, so it warns you about all the same side effects. Plus one more:

Narcan doesn’t have “risk of opioid overdose” as a side effect. Vivitrol does though.

Opvee, along with overdose reversal agents Kloxxado and Zimhi, and opioid use disorder medication Vivitrol, belongs to a growing category of opioid antagonist medications that have no reason to exist. None of the first three have any overdose-reversing capabilities that Narcan doesn’t already have, or that generic naloxone doesn’t do better. Vivitrol, which uses a different antagonist called naltrexone, doesn’t have the overdose-preventive capabilities that methadone and Suboxone already have.

What all four of them do have is a dose that’s either really high or really long-acting, and can put someone in precipitated withdrawal really, really easily.

Precipitated withdrawal is a term pharma companies are able to use casually because the public doesn’t quite get what it is. It’s not just “opioid withdrawal symptoms,” as Indivior describes it. It’s all those symptoms all at once with no warning, and then when people try to get well they can’t. People who use opioids die because of it. It leaves them in so much pain that they often use even more fentanyl than the amount that caused the overdose.

“Renarcotization,” the term that describes the effects of an opioid (like fentanyl) returning once an opioid antagonist (like naloxone) wears off, is essentially a made-up problem. Pharma companies, however, take it very seriously. The phenomenon is physically possible, sure, but it’s not the reason that people who’ve just overdosed often overdose again. “Attempts to overcome the blockade” caused by products like Opvee or Vivitrol—that’s the reason.

Reviving someone with an opioid antagonist isn’t supposed to be painful for them. But it often is, because they were given a much higher dose than was necessary. Though Narcan can also precipitate withdrawal, as can Suboxone, it doesn’t have to. But precipitated withdrawal is almost guaranteed by antagonist products that start off with higher doses, and prolonged by those with longer-acting doses.

Top image and inset slide via United States Department of Health and Human Services.