People who use drugs and a service provider are fighting legislation enacted by the Ontario provincial government which, if implemented, would shut down at least 10 supervised consumption sites by March 31.

Two participants at supervised consumption sites (SCS), Katharine Resendes and Jean-Pierre Aubry Forgues, along with SCS operator the Neighbourhood Group Community Services, have applied with the Ontario Superior Court for an interim injunction to stop the new law taking effect.

The matter is expected to go to a hearing in the coming days, with applicants hoping for a decision before the legislation’s implementation date.

The application seeks a finding that the Community Care and Recovery Act is unconstitutional.

Ontario’s Progressive Conservative Party passed legislation in December to ban SCS within 200 metres of schools, childcare centers and similar facilities—a law that would shut down 10 of the province’s 17 sites.

The application seeks a finding that the Community Care and Recovery Act (CCRA) is unconstitutional, claiming the law goes beyond the powers of the Ontario government.

Under the Canadian Constitution, federal law has “paramountcy,” and the closure of the sites, the applicants say, would go against Controlled Drugs and Substances Act exemptions for SCS approved by the federal government.

A factum they filed also alleges the law violates Sections 7 and 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms—respectively, the right to life, liberty and security of the person, and the right to equality.

Under the former, the legal filings argue the law increases the risk of death for Resendes and Forgues, calling the effects “arbitrary, overbroad and grossly disproportionate to the objective it ostensibly seeks to obtain.”

The legislation was introduced with the ostensible aim to improve public safety, citing public drug use outside the sites.

“In Toronto, around 90 percent of the people who use these sites are unstably housed or homeless. People will instead use what is readily available: public places.”

But Colin Johnson, co-chair of the Toronto Harm Reduction Alliance, said in a March 20 public video conference about the case that the law wouldn’t address that—and in fact would exacerbate it.

“In Toronto, around 90 percent of the people who use these sites are unstably housed or homeless, meaning they don’t have a place indoors of their own,” he said. “People will instead use what is readily available: public places, such as alleyways, parks. People will use public washrooms, in libraries, businesses and community centers.”

Injecting drugs in unhygienic spaces will increase people’s risk of infections and abscesses, Johnson added. People will also be more likely to share drug-use supplies like syringes in the absence of SCS, increasing the risk of HIV and hepatitis C transmission. And when people are not using in places designated for drug use, response times to overdoses will increase, putting people at risk of brain damage and death.

SCS closures “will, without doubt, cause unnecessary and preventable harm to some of the most marginalized people in our communities,” Johnson said.

With respect to Section 15, the court filings say the closure of SCS “imposes disproportionate burdens on those experiencing substance use disorder, a recognized disability,” adding that the approach “perpetuates and exacerbates existing disadvantages that this group already experiences, including the false and pernicious stereotype that these individuals are dangers to the community, not members of it.”

Resendes and Forgues contrasted the stigma they experienced in abstinence-based treatment with their positive experiences at SCS, where they found community and stability.

The two individual applicants, Resendes and Forgues, are both aged 36 and have long experienced substance use disorders.

In affidavits referenced in the filings, the two contrasted the stigma they experienced in abstinence-based treatment with their positive experiences at SCS, where they found community and stability.

The factum, referencing case conferences that heard expert testimony from both parties, notes that the applicants are backed by strong evidence showing SCS have a positive effect on health in their surrounding neighborhoods, that they don’t affect crime rates and that Ontario’s legislation is likely to increase overdose deaths.

“Ontario’s experts did not conduct any studies of the effects of SCSs in Ontario and therefore could not provide any positive evidence about this issue; they only critiqued the evidence of the applicants’ experts,” the factum reads.

The filings add that there were “several issues” with those critiques. Whereas the applicants’ experts were “candid and noted where their opinions had limitations,” the factum claims the government’s experts “lacked similar candour, and several of them seemed to misunderstand the appropriate role of an expert.”

That refers, among others, to Dr. Sharon Koivu, an addictions doctor with no criminology experience, who “gave opinion evidence on bias in the reporting of crime. When confronted with the fact that this was an opinion that was outside the area of her expertise, Dr. Koivu asserted that she felt it was within her duty to give such opinions.”

Lawyers note that finding real estate not in an area where the new legislation bans SCS “will be akin to finding a needle in a haystack.”

Dr. Robert Platt, meanwhile, reportedly gave evidence on the ease with which an SCS could relocate, “despite having not had any discussions with any of the operators of SCSs in Ontario, having no expertise on the real estate or rental market in Toronto and not having reviewed the map in Ontario’s record setting out the CCRA restricted locations.”

In the factum, lawyers note that finding real estate not in an area where the new legislation bans SCS “will be akin to finding a needle in a haystack,” with “only a few slivers of land here and there [that] are left uncovered.”

“And that is without considering zoning issues or pre-existing structures on that land [that isn’t covered by the ban],” the factum reads.

The legal filing includes a map of the Toronto area, with circles indicating the areas where SCS are due to be banned.

Sites that are set to close can’t simply relocate, the factum adds, as the law also “prohibits municipalities and local boards from applying for federal [Controlled Drug and Substances Act] exemptions to operate an SCS without the Minister’s approval.”

This doesn’t just affect sites in Toronto, which will lose half of its SCS if the legislation comes into effect, noted Zoë Dodd, a co-organizer at the Toronto Overdose Prevention Society.

“They’re also closing the only sites in several cities, including Hamilton, Guelph and in Thunder Bay,” she said in the video conference. “They wouldn’t fund two amazing sites in Timmins and Sudbury that were doing great, and saving lives. And those sites had to close last year.”

“By forcing the site in Thunder Bay to close, they are closing the last site in the northern part of this province, where the death rate from overdose is double the rate in the southern part,” Dodd added.

Sites have also already closed in Ottawa and Peel, and Dodd said that this has resulted in increases in public use and in overdoses.

“The government defunded these in August,” she noted. “They gave organizations a letter saying they were being defunded before the legislation even passed.”

“We already know the impacts, people are already seeing people overdose elsewhere and trying to respond,” Dodd continued. “And we know that in places that they’ve already closed, they’ve had to ramp up paramedics and outreach workers to respond to people outside.”

“How do we not get fooled by stigma and fear?”

The Canadian Drug Policy Coalition is acting as an intervener in the case, and executive director DJ Larkin said during the video conference that they intend to clarify for the court the harms that will arise from closing the sites.

“The job has to be to assess what is the real and most important harm that we have to prevent,” Larkin said.

“How do we not get fooled by stigma and fear, and how do we make sure that government doesn’t get to impose a law that is harmful in order to try to hide people and harm people who are already suffering from failures of government around housing, around health care, around treatment services, around basic essentials of life and dignity?”

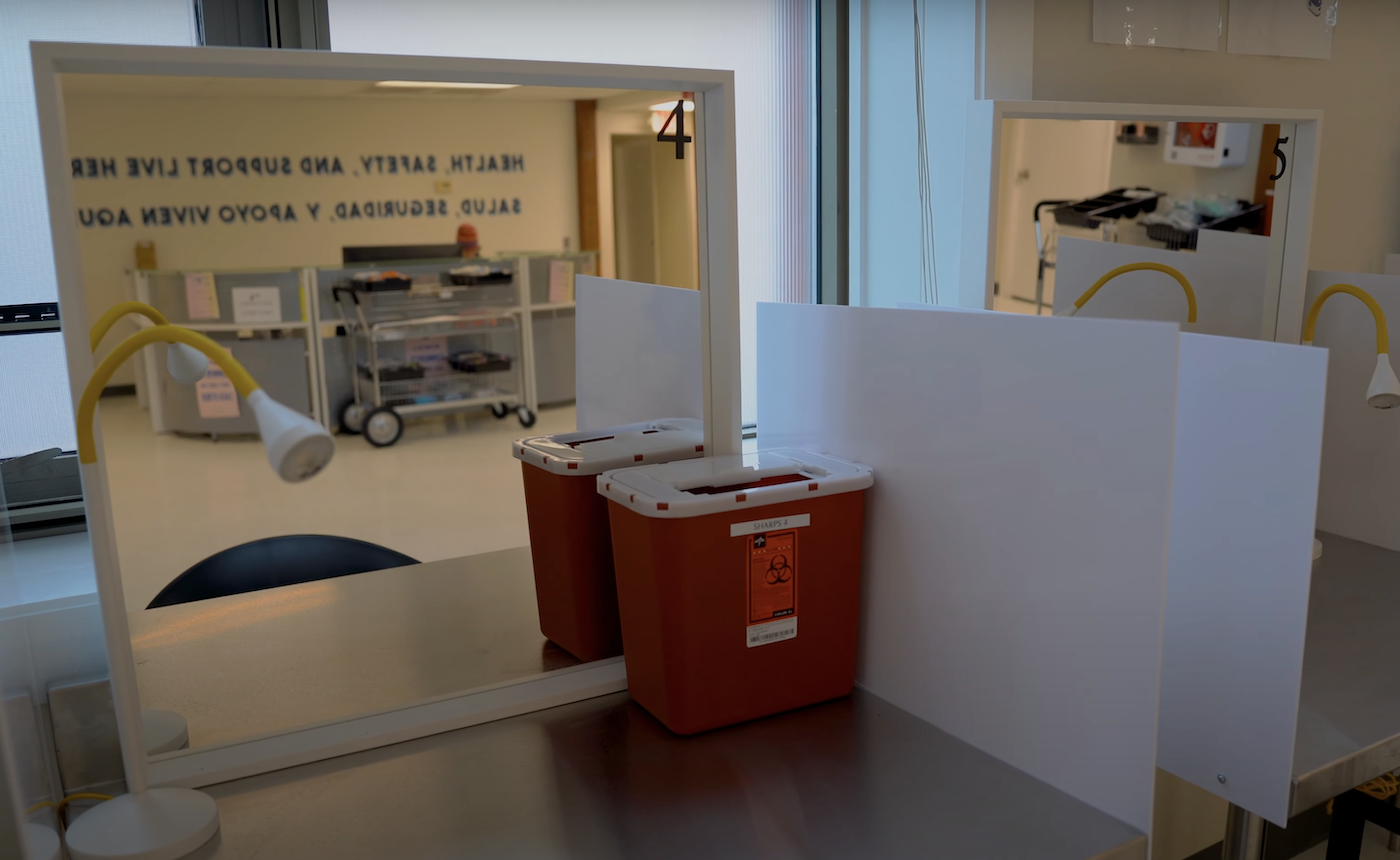

Screenshot from film of overdose prevention center in Providence, Rhode Island, by Marilena Marchetti