One of the greatest hypocrisies in medicine is the restriction of standard-of-care medications for health professionals with opioid use disorder. A perspective article published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year called for an end to physician health programs’ de facto bans on doctors receiving methadone or buprenorphine treatment.

However, these medications are not only restricted for doctors. Nurses can also be mandated to a medication-free—or abstinence-only—form of recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD).

Although health professional monitoring programs vary state-to-state, often operating independently with no oversight, many effectively restrict what is considered the gold standard for treating OUD. They typically create complex systems—requiring expensive and hard-to-obtain neurocognitive testing, for example, to determine impairment—before OUD medications can be approved for nurses. (The jury is out on whether the medications cause any impairment.)

The unspoken primary mechanism creating both this mythological concern for impairment and the general controversy over pharmacotherapy for healthcare professionals with OUD is stigma.

When I called my case manager, her first comment was, “Well, Bill, you know most people who use Suboxone abuse it anyway.”

I am a nurse in sustained recovery from opioid use disorder and a participant in a nurse monitoring program (Pennsylvania Nurse Peer Assistance Program, or PNAP). However, my fight to enter and sustain my recovery has succeeded despite the monitoring program, not because of it.

Nothing in writing outwardly indicates that PNAP prohibits bupe or methadone. But when I called my case manager to inquire, on behalf of another nurse, her first comment was, “Well, Bill, you know most people who use Suboxone abuse it anyway.”

In practice, if a nurse wants to be on buprenorphine and has a clear plan to taper off, PNAP will allow them in the program—and monitor them via drug screens until they taper off, and then continue screens for three years to ensure they stay off. If a person says they want to be on the medication indefinitely, PNAP will not allow them in the program and the nurse will be referred to the licensing board.

My case manager said that the licensing board will require “extensive neurocognitive testing to make sure they aren’t impaired on the medication and this testing is very expensive and difficult to find anyone who does it.” Her tone led me to believe no one would ever be cleared for licensure while taking the medication.

As a person who struggled with opioid addiction during the current age of fentanyl analogues contaminating the drug supply, I was at high risk for fatal overdose. Currently, well over 100 Americans die each day from overdose—a completely preventable cause of death. Opioid agonist medications such as buprenorphine and methadone can reduce this risk by 50 percent.

During my journey to recovery I entered inpatient treatment centers 16 times over an 18-month period. On 13 out of those 16 occasions, I could not abstain from use for more than four-to-six days, and left treatment.

Seven times after I was discharged from treatment, I experienced unmanageable cravings and sought relief, resulting in overdose.

Although I desperately wanted to recover from OUD, the intense cravings I experienced, coupled with unbearable symptoms of physical withdrawal, made it almost impossible for me to navigate these situations. So each time I returned to using opioids, with heightened vulnerability to overdose because of reduced tolerance after my brief period of abstinence.

Seven times after I was discharged from treatment, I experienced unmanageable cravings and sought relief, resulting in overdose. Thankfully, my wife found me on each occasion and administered naloxone.

During most of those inpatient visits, I was offered OUD medications. However, restoring my career was a primary goal for me. As a nurse, my understanding was that methadone and buprenorphine were prohibited—or at least unreachable due to policies and financial commitment.

So I continued to chase the white-knuckle, torturous goal of abstinence.

In addition to limits on medications, monitoring programs often mandate a path of recovery heavily embedded in the 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous—a self-help program, created in 1939, that involves attending meetings, prayer and ridding oneself of “character defects.” Many people find 12-step fellowships helpful, but most don’t—estimates of success rates are very low. People should be free to choose this path if they wish, but not required to follow it.

My program required an initial 90 12-step meetings in 90 days (a typical unscientific practice in these fellowships), followed by three meetings per week for three years. Health professional monitoring programs commonly require this—although Bryon Wood, a former nurse in British Columbia, Canada, recently won his years-long legal fight to get the policy overturned there.

I still have to attend these meetings today, and PNAP tracks my attendance via GPS through my cell phone. Moreover, I am required to submit a monthly progress report outlining my efforts in the program. Each month, I write in these reports how harmful meetings have been to my personal life, yet I am still mandated to continue.

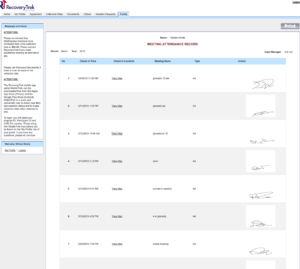

The author’s mandated AA meeting sign-in sheet

PNAP participants are also subject to random drug screens. These screens must be witnessed, which means the person providing the specimen must be physically observed as the urine exits their body by the person collecting the sample. This practice often generates anxiety and shame for the person providing the sample, as I have also stated in my reports for PNAP.

It operates on the assumption that the subject is dishonest, based solely on the myth that people with substance use disorders are liars and thieves. PNAP further perpetuates this discriminatory narrative when educating professionals about “signs” of substance “abuse.”

Behaviors such as dishonesty, when they occur, are not a byproduct of substance use disorder. Rather, they are a complex coping mechanism, related to unjust policy and the shame often imposed by healthcare professionals, reflecting how difficult it is to safely communicate about drug use given severe legal, social or professional consequences.

Testing also comes at an inflated cost, which is not covered by insurance. As the New York Times has reported, urine is a big money-maker in the addiction treatment industry, giving it the nickname “liquid gold.”

In my own case, my wife and I ultimately had to file for bankruptcy as a result of piling debt from treatment costs and monthly fees associated with such monitoring. Being unable to work as a nurse, I had to take a $9/hour retail job, which made it impossible to dig ourselves out of the financial hole.

These programs need to begin developing individually designed, participant-led recovery paths.

Monitoring programs for healthcare professionals are an essential part of public safety. A licensing board carries the great responsibility of ensuring that license holders are safe to practice. However, these programs have an equal responsibility to the nurses and physicians for whom they advocate.

Recovery from substance use disorders is not typically a linear path or a one-size-fits-all prescription. If these programs truly care about public safety—and not just checking off boxes to demonstrate an intervention was completed—they need to begin developing individually designed, participant-led recovery paths.

These options must include standard-of-care medications and evidence-based practices. Twelve-step attendance should never be mandatory, and good-quality therapeutic interventions should be available. Out-of-pocket costs for participants, which are often a barrier, should be eliminated.

Nurses as a group are rarely the subject of policy advocacy, but are severely subjected to stress, mistreatment and discrimination. Those with substance use disorders deserve far better than the restricted, anti-evidence options currently available.

Supporting Nurses Who Use Substances

One illuminating call for a better approach recently came from the Harm Reduction Nurses Association (HRNA) in Canada. The group issued a position statement on February 6, titled “Supporting Nurses Who Use Substances.”

“The prevalence of problematic substance use among nurses is similar to the general population,” it noted. “However, it tends to be underreported largely due to the overly disciplinary and non-supportive approach used by employers, regulatory bodies and unions.”

Indeed, my admittedly anecdotal experience suggests that job-related stress leads to particularly high rates of substance use disorders in this population, masked by a culture of silence.

Five of HRNA’s 13 demands were as follows:

* Nurses should be granted the freedom and autonomy to use psychoactive substances when off work—and not held to a different standard than the general public.

* Nurses with suspected problematic substance use should not automatically be put on leave pending their assessment. Instead, a risk management plan should be developed using the same approach used for other conditions that may result in performance impairment.

* Treatment plans should be individualized, patient-centered, secular and evidence-based, and free from any form of coercion. They should measure up to the best standard of care in the field and be consistent with the quality of health care offered to other citizens.

* Nurses with problematic substance use should not be singled out and subjected to a different level of scrutiny than nurses with other health conditions or injuries. Workplace accommodations should be provided with the same level of consideration and flexibility.

* Complete abstinence from all psychoactive substances should not be used as a treatment goal. Treatment goals should be tailored and developed collaboratively to reflect the state of evidence and principles of harm reduction.

Blocking lifesaving medications for nurses in the US reflects our country’s love affair with the War of Drugs—driven in turn by our Temperance-rooted cultural notion that total abstinence is the only “good” lifestyle.

The requirement that healthcare professionals engage with a program that says we should “turn our will and our lives over” to a masculine god and penitently make amends to every person we have harmed throughout our entire lives has much to do with shaming and nothing to do with science.

In centuries past, we assigned illness to demonic forces and relied upon prayer, or worse, to relieve us of our ailments. It was modern medicine that moved us past such archaic interventions.

How cruelly ironic, then, that in 2020, medical professionals are still forced to pursue a spiritual “remedy” for substance use disorders, and an abstinence-only path that increases their risk of finding not recovery, but death.

Photo by Artur Tumasjan on Unsplash

Show Comments