In the past two months, both Denver, Colorado and Oakland, California decriminalized psilocybin mushrooms (and in Oakland’s case, other naturally-occurring psychedelics like ayahuasca and iboga). Police in these cities have now been directed not to arrest and prosecute people for personal use or possession. Meanwhile, the cities’ governments are reviewing plans for further reforms or lobbying their county and state-wide counterparts to advance these policies.

In both the Decriminalize Denver and the Decriminalize Nature Oakland initiatives, psychedelic activists made explicit public health arguments, explaining that these substances are powerful tools for treating conditions like depression or substance use disorders. But as new populations exercise limited freedom to use these drugs, the need for psychedelic education and support is greater than ever.

Activists are moving cautiously, knowing that the way things play out in Denver and Oakland will be heavily scrutinized by other jurisdictions—and by opponents of decriminalization. There’s pressure not to over-step, and to get the messaging right.

Working Within Restrictions in Denver

Joey Gallagher runs the Psychedelic Club of Denver, which operated pre-decriminalization, since 2017. The club meets regularly to discuss psychedelic science, culture and more. But it strictly does not facilitate drug use or distribution at its events.

“We’re just community organizers, we’re not shamans or therapists or anything,” Gallagher told Filter. “We read books, watch films and share knowledge with our crowd—or we host organizations like the Zendo Project or DanceSafe to talk about harm reduction and safe practices.”

Gallagher says the Psychedelic Club hosts between 20 to 30 guests at each of its meetings. Meet-ups and public events like these are now the main way that Denver’s psilocybin activists are educating the public about these substances after decriminalization.

“Our biggest opponent is still our mayor. He has this idea we’re attracting a poor image of a ‘drug city.’”

He cautioned that despite decriminalization, most psychedelic activity is still illegal in Denver. People can’t have events and encourage others to trip, or host people in their homes or businesses and give psilocybin therapy services. “People who already use psilocybin may feel more empowered, but I don’t think use is rising,” Gallagher said. “They are looking for the next step, whether it’s the medical model, legalization, or decriminalization throughout the state or the whole country.”

Psychedelic advocates in Denver work with the knowledge that despite I-301’s success at the ballot box, psilocybin does not yet enjoy full political support in the city. “Our biggest opponent is still our Mayor Michael Hancock,” Gallagher said. “He has this idea we’re attracting a poor image of a ‘drug city.’ But to us it’s actually a good image to be a tolerant city, to be tolerant of different people’s medicines and lifestyles.”

Members of the Psychedelic Club of Denver (photo courtesy of Joey Gallagher)

Psychedelic Outreach in Oakland

Oakland faces a more complex challenge, because its decriminalization initiative applied to several groups of drugs. Activists there are working to tailor their approaches to different populations.

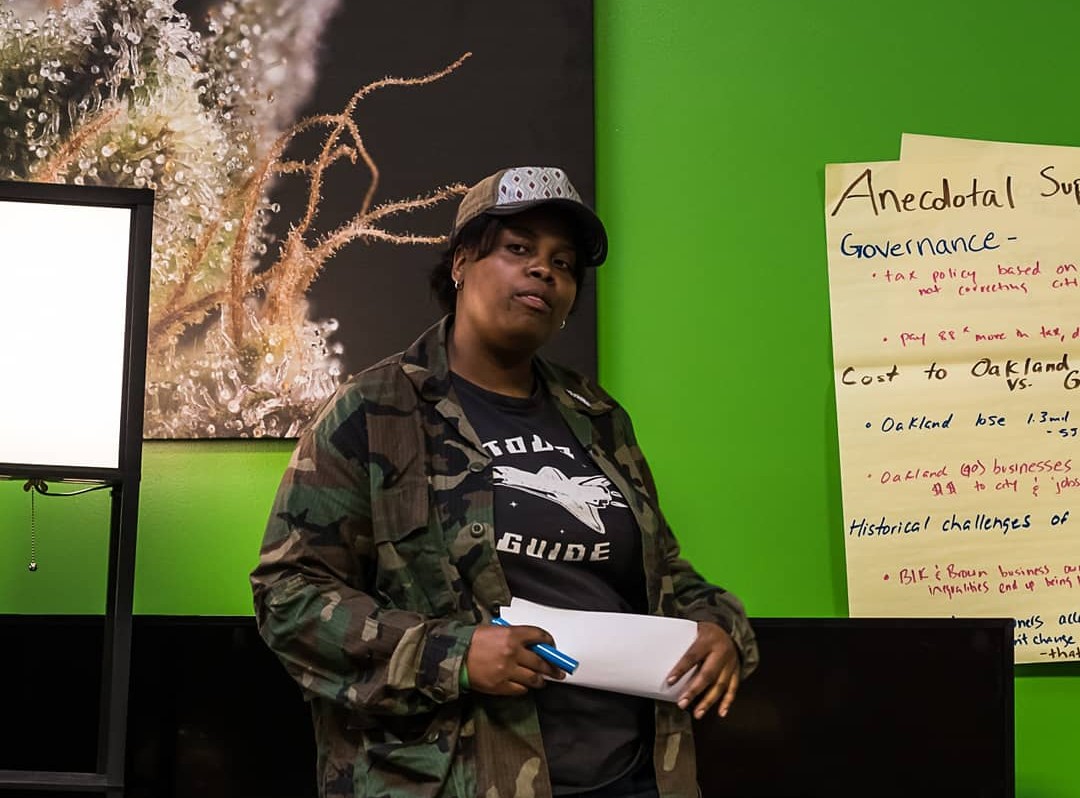

“Right now we’re putting together an outreach plan for how to approach Asian, Latino and African-American communities,” said Amber E. Senter (pictured top), co-founder of Supernova Women and a Decriminalize Nature board member. “We’re developing workshops to introduce people to what these plant medicines are and how they can be useful to them. There’s definitely an increased interest in entheogens, as we’ve had many folks reaching out to us who are curious to learn more.”

The psychedelic reforms in Oakland will play out differently than cannabis legalization, according to Senter, because the population of people who are knowledgeable about psychedelics is much smaller. “People in California have had a relationship with cannabis for a very long time,” she said. “They know its effects, and they know other people who use. That conversation is much more advanced than with these substances where they likely don’t know what their effects are or don’t know anyone who has used them.”

“It’s about having a conversation with different folks rather than coming from the outside and speaking at them.”

Kufikiri Imara, another Decriminalize Nature board member, believes that the style of public outreach is as important as its content. “Our big focus is partnering with the people and organizations who are already engaged and showing up to better these communities,” he said. “We want our message to be rooted in their own knowledge and language. It’s about having a conversation with different folks rather than coming from the outside and speaking at or to them.”

Both Imara and Senter acknowledge there is an existing, active underground community of people working with entheogens or performing psychedelic guidance ceremonies. But like Gallagher in Denver, Imara agrees that decriminalization does not completely open the door to legal psychedelic therapy in his city. County, state and federal statutes are still in full force, as the Decriminalize reform was only passed by a City Council resolution.

“This doesn’t give someone a blank check and a clean slate to do whatever they choose,” he said. “People still need to be very mindful in how they’re operating. A road to legalization would require a lot more legislatively, including codes of law, regulations, taxes, and everything else the cannabis industry is handling now.”

Keeping Focus on Wider Drug Policy Reform

Jag Davies, a drug policy consultant with many years of experience in psychedelic policy at Drug Policy Alliance and MAPS, told Filter that decriminalization of psychedelics is a small step towards ensuring the safety—and legal rights—of people who use drugs in general.

“All drugs, no matter their potential benefits, come with inherent risks,” he said, “which are vastly amplified by their criminalization. There’s always a need for community education to ensure safety—in fact, in places where psychedelics remain criminalized, the need may be even greater.”

He also cautioned that further reforms, like making psychedelics into prescription medicines, will only eliminate criminal penalties for people who use them in the appropriate government-sanctioned and doctor-approved places—a small fraction of the total drug-using population. And he’s wary of an excessively psychedelics-specific drug policy strategy.

“Decriminalizing all drugs, not just certain psychedelics, is both a more ethical and a more strategic approach,” he said, “given the broad scientific and political consensus in favor of significantly reducing the role of criminal penalties in drug policy. By prioritizing psychedelics, we run the risk of perpetuating the drug war and the mentality that gave rise to it.”

“Psychedelics are going to be much bigger than even the cannabis revolution—stay tuned.”

The organizers behind both the Denver and Oakland initiatives have publicly stated that they hope these efforts can help build public consensus for further decriminalization of all drugs. But they are also clearly centering this debate on the power of psychedelics to support mental and spiritual well-being.

“We want to show how working with these plants is a component of a larger mindful practice that can be incorporated into peoples’ lives,” said Kufikiri Imara. “And their value comes from integrating the lessons and knowledge you receive from those experiences.”

But for Joey Gallagher, it gets even simpler than that. “These plants aren’t just for medical use,” he said. “They can be safe for recreational use and even healthier than some drugs that are already legal. Besides that, people simply deserve the right to use them. Psychedelics are going to be much bigger than even the cannabis revolution—stay tuned.”

Photo courtesy of Amber E. Senter

Show Comments