After stalling cannabis legalization in spring 2019, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed into law a bill that decriminalizes small-quantity marijuana possession and offers routes for record expungement.

While state legislators like Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie praised the new law as an “important step in righting decades of injustice,” progressive drug policy reform advocates say it misses the mark on repairing harms against communities most impacted by the drug war.

Signed on July 29, the new law (S.6579A/A.8420) axes criminal penalties for possessing amounts of marijuana under two ounces. Instead, this will be considered a civil violation. Possessing less than one ounce comes with a maximum fine of $50, while defendants with more than that can face up to a $200 penalty. When the law takes effect on August 29, all counts pertaining to the relevant charges will automatically be vacated and dismissed, and existing records expunged.

Cuomo recognizes that “Communities of color have been disproportionately impacted by laws governing marijuana for far too long. But he believes that “today we are ending this injustice once and for all.”

To the contrary, advocates at the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA),* headquartered in New York City, argue that the work of crafting equitable drug policy is far from over.

For one, legislators’ characterization of the legislation as overturning injustices against communities of color is ill informed, said Melissa Moore, DPA’s deputy state director for New York. “It is critical that this bill is not mistaken as a ‘decriminalization’ measure, despite how lawmakers have advertised it,” she said. “As we have seen in the years following New York’s so-called decriminalization of marijuana in 1977, anything short of comprehensive legalization means that Black and Latinx individuals will remain disproportionately in the crosshairs of harmful enforcement practices.”

According to the text of the bill, 44,600 people in New York State have still been arrested and charged with a misdemeanor marijuana offense between 1977 and 2012, with prosecutors exploiting loopholes that continued to criminalize the “burning” of marijuana, or possession “in public view.” The number of people criminalized after supposed decriminalization grows even higher when arrests alone are considered: from 1977 to 2017, more than 800,000 people were arrested in the state for possession of small amounts of the drug.

Those still criminalized for possession of small quantities are overwhelmingly people of color. In 2015, 88 percent of the 16,590 people arrested in New York City for marijuana possession were Black or Latinx.

“Decriminalization alone is not enough to deal with the full impact of marijuana prohibition and just gives law enforcement discretion,” said Moore. She believes a broader systemic program is need to repair the harms of prohibition.

“Given the extensive, life-changing inequities created by discriminatory and draconian enforcement policies, true justice requires the allocation of tax revenue to community reinvestment programs for impacted communities,” said Moore.

State and local programs that aim to do this include those in Massachusetts and Portland, Oregon, although some social equity programs have been beset by serious shortcomings. One model for doing this on a federal level could be Senator Kamala Harris’s recent marijuana legalization bill, which distinguishes itself from other proposals by establishing social equity programs.

“While it is disappointing that our leaders have once again failed to address marijuana criminalization wholesale,” said Moore, “we will continue to fight on behalf of comprehensive marijuana reform in New York.”

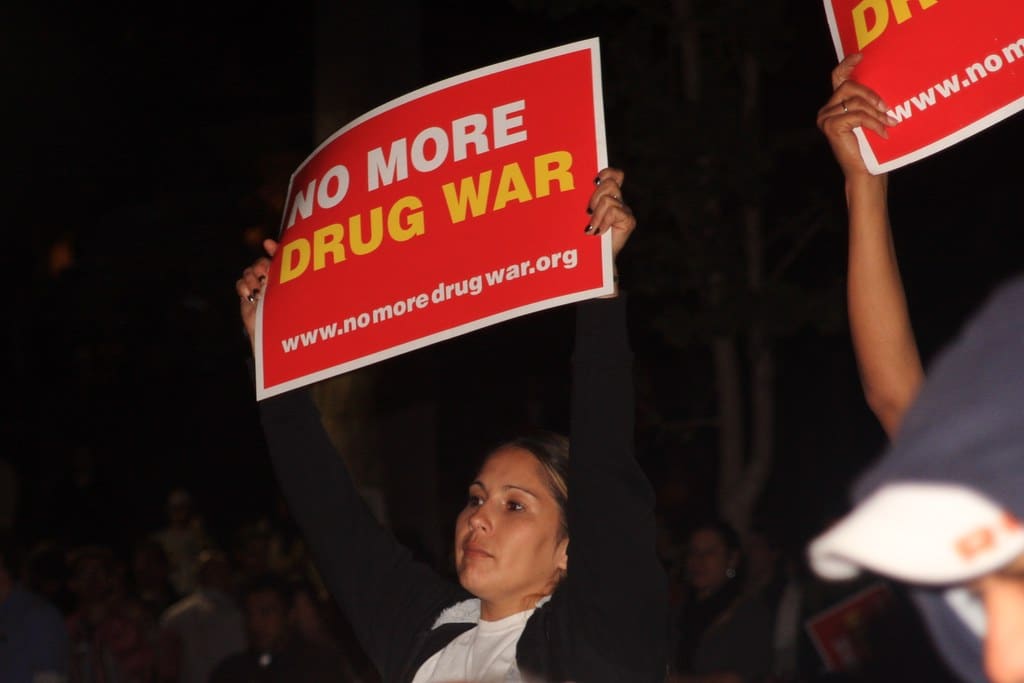

Photograph of participant at Rally & Concert to End the War on Drugs in MacArthur Park, Los Angeles in 2011; by Nikki David via Flickr

*The Influence Foundation, the nonprofit organization that operates Filter, has received a restricted grant from DPA to support a Drug War Journalism Diversity Fellowship.

Show Comments