When I walk into my local pharmacy to pick up a naloxone kit, I don’t need to present a prescription. I don’t even need to state my reason for needing naloxone (I’m an opioid-dependent pain patient and I frequently interview people who use illicit opioids). The pharmacist asks whether I prefer the nasal spray or the injectable version, then takes me through a five-minute orientation, explaining how to use it to save someone else’s life. Then I leave with my kit.

No money changes hands. I owe nothing. My choice of injectable versus nasal spray is driven by my own comfort, not by their respective costs.

I live in Toronto. But in the United States, where the crisis of opioid-involved overdose deaths is raging (as it is in Canada) beyond anything we’ve seen before, naloxone access is limited—not just by stigma and outdated, restrictive laws, but also by its rising cost.

The access issue is common to most countries. The cost barrier, however, is somewhat specific to the US, with an average out of pocket cost of $31.01 in 2018. A single dose of generic naloxone in the European Union costs the equivalent of around $3.

Various ways to remedy this are proposed—some of them innovative, and ranging from market-based approaches to government-led ones. International examples show that the US could do better, but experts are skeptical about whether it will.

Naloxone is not a new drug. It was first patented in 1961 as a medication to reverse the common side effect of constipation in patients prescribed opioids, but was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for overdose reversal in 1971. The original patent expired long ago, so today the generic version only costs around $20. But new delivery systems—like the auto-injector and the nasal spray—have allowed for new patents, of which there are currently seven, with the auto-injector and nasal spray not due to expire until 2035. In effect, companies are now charging for the delivery system, not the drug itself.

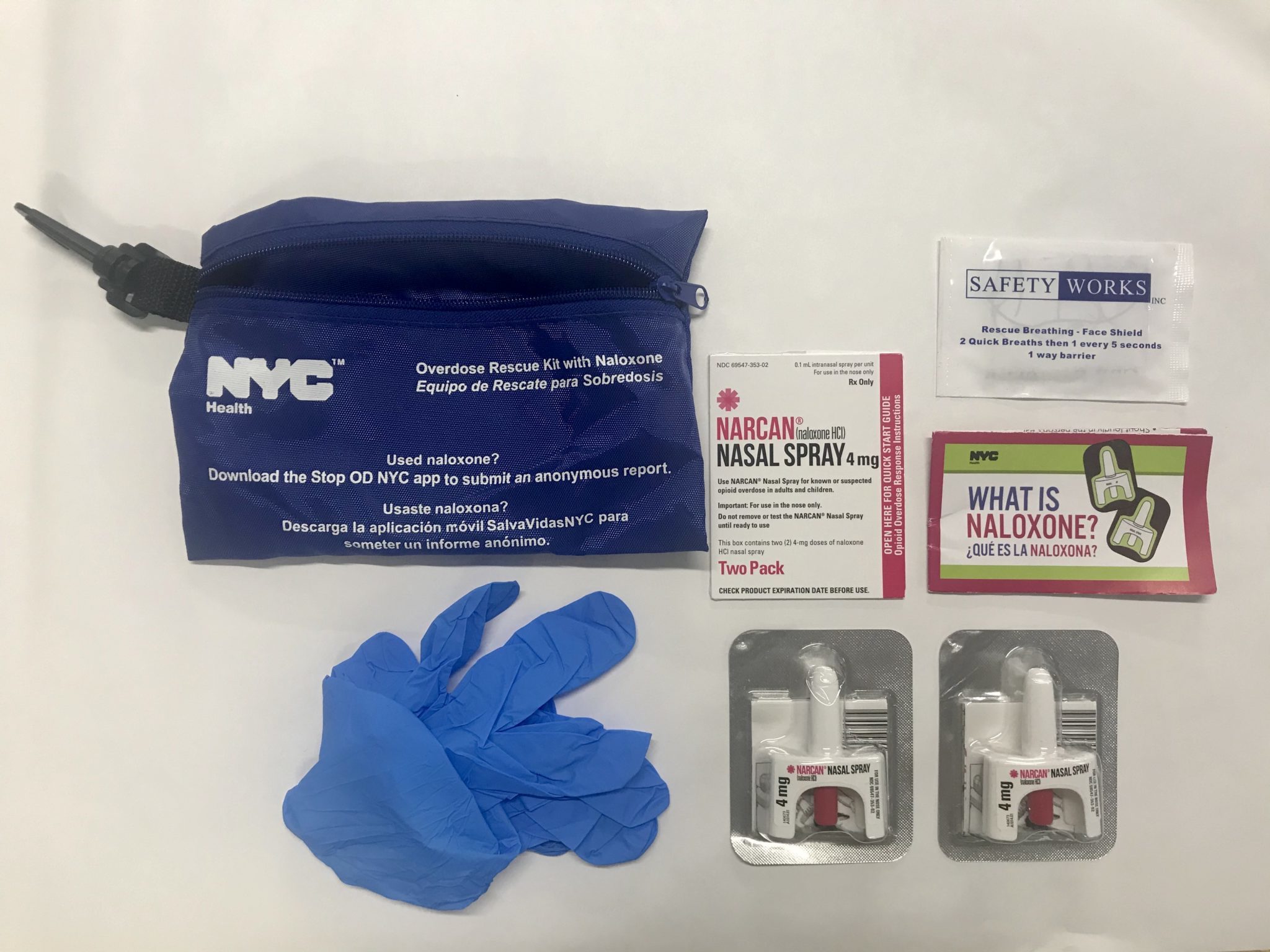

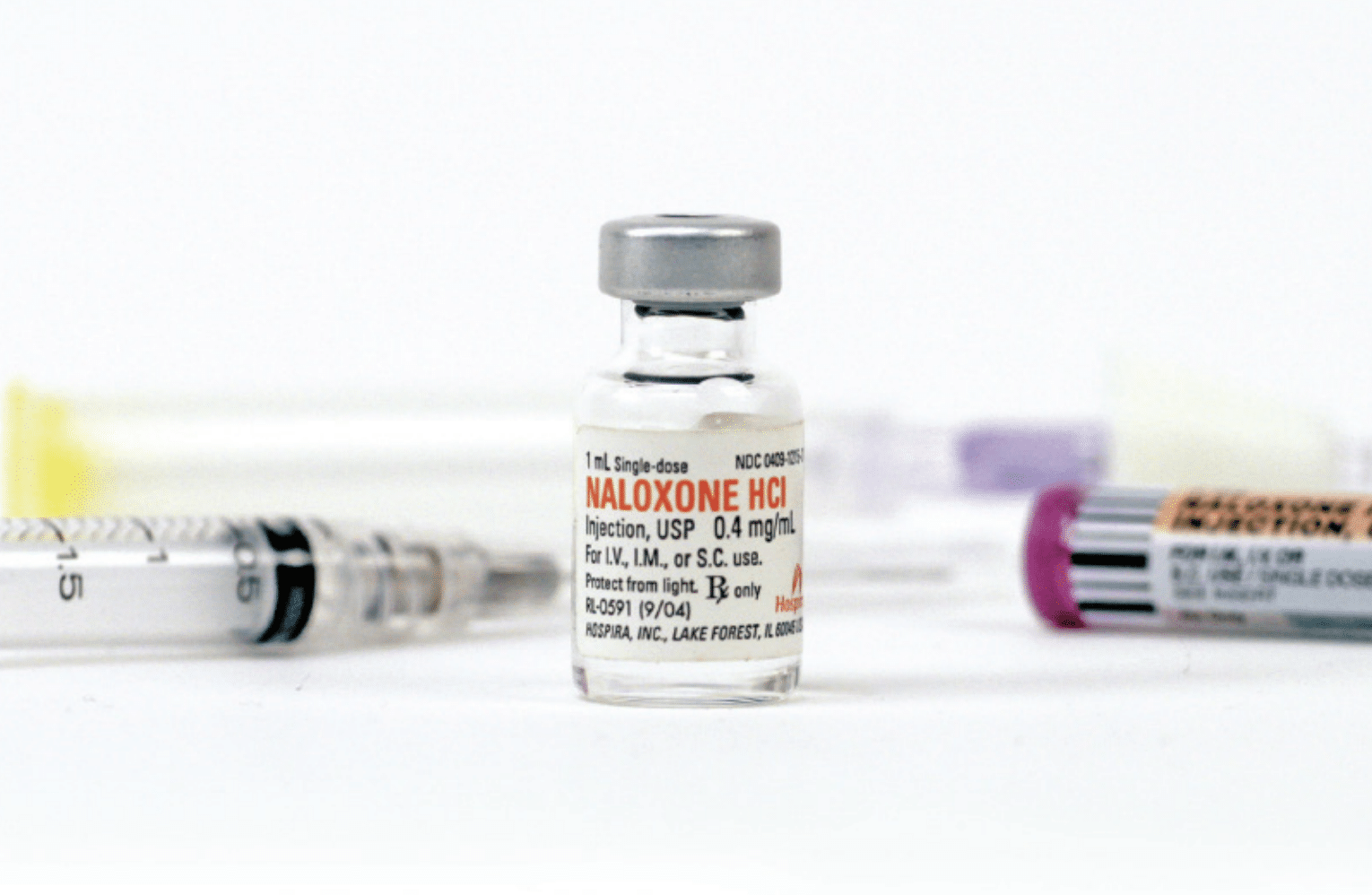

Narcan is the brand name for nasal spray naloxone. By contrast, injectable naloxone is administered by first filling a syringe from a small vial and then injecting that into the muscle of the thigh or shoulder. The injectable form is the cheapest, because it’s not covered by patent. Then there’s the auto-injector, Evzio, which you administer through an EpiPen-like delivery system.

No Standard Access

There is no standard way of acquiring naloxone in the US. Across the country, different people and organizations do so in different ways.

In San Francisco, the National Harm Reduction Coalition’s DOPE Project (Drug Overdose Prevention and Education) provides free injectable and nasal spray naloxone to people who use drugs. For the former, it relies on a deal painstakingly arranged by unpaid harm reductionists working with the pharmaceutical company Pfizer, which owns Hospira, the makers of injectable naloxone hydrochloride. This “ensures access to injectable doses of Pfizer for a cost I can’t disclose,” said DOPE Project manager Kristen Marshall. “That is the way historically anything has to get done when you are representing people outside the mainstream.”

The DOPE Project gets its Narcan, meanwhile, through a state-funded naloxone distribution program. “There’s no way we’d be able to afford that [without the program]. The fact that not every state has that kind of access is a problem,” Marshall said. “In places like West Virginia, where we’re seeing the highest rates of overdose deaths and HIV, that’s not available.”

Like harm reductionists elsewhere, she sees access to the nasal spray as vital. At a time when many people are smoking fentanyl and overdosing without ever having used a syringe, syringe-based naloxone can pose a barrier. She also noted that many venues—jails, libraries, hotels—are unwilling to keep syringes on hand.

“It’s infuriating how these resources go to the carceral system.”

NEXT Distro, a New York City-based organization that distributes harm reduction supplies, gets its expired naloxone from the sources that actually have funding, often through large state grants, to purchase it: fire departments, police departments, jails, clinics, hospitals, security companies and certain community-based organizations.

“[Federal and state] grants are prioritizing funding for inefficient systems that are not suited to the needs of people who use drugs,” said Jamie Favaro, NEXT Distro’s executive director. “It’s infuriating how these resources go to the carceral system.”

So Favaro makes it easy for staff at fire departments or jails to find NEXT Distro online when they search for places to donate naloxone that inevitably expires unused. They recently received 800 doses (from a source she preferred not to reveal), which NEXT Distro is now pumping out to secondary suppliers—harm reduction organizations, often in southern states where naloxone is difficult to access (they try to redistribute the supply in the same state from which it was donated). But it’s often a “feast or famine” situation, in that they can’t rely on a steady supply of the expired naloxone that powers their work.

In her 2020 book, OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose, author and academic Nancy Campbell argues that the struggle for expansion of naloxone access fueled the harm reduction movement, turning overdose from a death sentence into an opportunity to fight for change. Building on the revolutionary zeal that animated advocacy for syringe access and blood-borne disease prevention, the fight for naloxone access became a fight to put lifesaving technology in the hands of the people best positioned to use it.

“It’s not just a technology,” Campbell told Filter. The story of naloxone is “laden with people.”

Pharma’s Evolving Role

Naloxone pricing says a lot about the way pharmaceutical companies operate in the US. In one sense, the story of naloxone is one of drug-user empowerment, as a lifesaving substance once confined to hospital and paramedic use was adopted by the people. In another, it’s a story of just how fragmented, how inequitable, Americans’ access to essential medicines truly is.

“I don’t think this addresses the historical issue of naloxone not being accessible to people who are low- or no-income,” Favaro said of NEXT Distro’s otherwise effective strategy. Indeed, case-by-case strategies that rely on the charisma or persuasiveness of individual harm reduction workers, and on carefully cultivated relationships with key organizations, are work-arounds for an inaccessible, inadequate system.

Like NEXT Distro and the DOPE Project, other harm reduction organizations and workers often have to forge unlikely and unreliable alliances with commercial or institutional partners in order to access this World Health Organization essential medicine.

“All those [marginalized] folks are left out of systems of care by design. That means we utilize individual relationships to get stuff done,” Marshall said. That reality “kills people. It runs workers into the ground. It’s not sustainable.”

This is the story that Campbell puts into historical perspective. Dan Bigg, the late, great founder of the Chicago Recovery Alliance, used his considerable moral suasion and charisma to get naloxone out of hospitals and into drug-user communities. He would show up at conferences with bags of the stuff and offer his support to others who wanted to start their own naloxone distribution programs.

In 1998, the CRA pioneered the world’s first take-home naloxone kits. By the early 2000s, prices were already rising. In 2008, Bigg went to Hospira and told them, “you’re going to put us out of business if you jack up the prices.” Working what Campbell described as his “moral entrepreneurship,” Bigg negotiated a lower cost for organizations using naloxone for overdose prevention, with the company continuing to charge higher prices to medical purchasers.

Companies that since the 1960s had taken no interest in the sales potential of naloxone were becoming aware that there was, in fact, a market.

From 2008 to 2013, then, state or city health departments were able to purchase the drug at a reasonable cost. Meanwhile, harm reduction activists across the country gradually got every state and the District of Columbia to change their laws on naloxone access, loosening legal liability at medical boards and legislatures nationwide (the degree of access and protection from liability, however, varies significantly).

Harm reduction organizations further convinced some states to issue standing orders—where rather than naloxone requiring a specific prescription for a specific purpose for a specific person, the chief medical officer of a state or county might write one prescription that would apply to any eligible buyer.

But increasingly, pharmaceutical companies that since the 1960s had taken no interest in the sales potential of naloxone were becoming aware that there was, in fact, a market for their product. A captive one. And so the price began to climb again.

In 2014, Virginia-based company Kaléo entered the naloxone market with an auto-injector, which doesn’t require the person administering it to fill the syringe. Thanks to its resemblance to the more familiar EpiPen, the auto-injector is friendlier to, for example, many parents of people at risk of opioid overdose. It cost around $700—at first.

Following outrage from legislators and advocates at what was, by 2017, the $4,100 cost of its Evzio auto-injector, Kaléo announced that it would sell an almost identical generic version of the injector for $178 per 2-dose kit.

The original patent for insulin was sold to the University of Toronto for around $1 to ensure it would remain available to the world. Yet in the US, insulin-dependent patients are forced to pay up to $1,200 per month. In the same way, naloxone is an essential medicine that the US has allowed pharmaceutical companies to price as a luxury product.

“I have so much anger towards the pharmaceutical-industrial complex,” Favaro said. She described requests from harm reductionists who told her, “‘I had eight people OD in my community in the past months and I’m desperate.’ People who are at their wits’ end. That’s also become much more deafening [since] COVID.”

This past fall, both Evzio and its new generic were discontinued—apparently, the company wasn’t interested in continuing to produce the drug without the sort of profit it was raking in before.

“Even at the low-price [sic] of $178, market dynamics and the entrance of alternative products dictated the difficult decision to discontinue manufacturing of the branded and the authorized generic products last year,” Kaléo director of corporate communications Caryn Foster Durham wrote to Filter.

This leaves people with either the basic injectable or the nasal spray. It remains to be seen whether the price of the nasal spray will now rise even further as ADAPT Pharma Operations Limited, the company that owns Emergent BioSolutions, which produces Narcan, takes advantage of its now-larger market share. (Emergent BioSolutions did not respond to Filter’s request for comment by publication time.)

Potential Paths to Improvement

So what is to be done? New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) has made standardized naloxone kits available for free at partner pharmacies, including both small local pharmacies and major players like Rite Aid and Walgreens. Elsewhere in the state, naloxone is funded by the AIDS Institute, which uses scarce resources to pay for it. In New York, as in other states, access relies on a piecemeal assemblage of regulations, funding programs and advocates.

And so, the ability to access affordable naloxone continues to depend upon who you are and where you live. Standing orders in many places ensure that people can access naloxone without a specific prescription (important for a drug where the patient is never the person who will administer it).

But Marshall doesn’t see much value in the standing orders for her criminalized, marginalized, drug-using clients; they mean you can get nasal naloxone for $75—if you feel comfortable approaching the pharmacy counter. For most of the people she serves, both pharmacy and retail access remain fraught because of discrimination and racial profiling. Besides, she said of the relatively high price, “no one will pay for that.”

“The system is broken—the price rising as the crisis unfolds.”

As a medical student at Yale, Ravi Gupta took an interest in pharmaceutical costs and co-authored an important 2016 paper on the subject of naloxone pricing. It speculated that a small number of producers may be responsible for startling increases—such as the 500 percent hike for two doses of Evzio over a period of just two years, or Hospira’s 129 percent hike for injectable formulations between 2012 and 2016.

Gupta and his co-authors proposed that the government provide a stable buyer by bulk-buying naloxone for distribution. They suggested that the various legislative attempts to rein in the cost of prescription drugs in the US should explicitly call on manufacturers to reduce prescription drug prices and to be more transparent about costs and reasons for increasing them.

“The US government could take over existing patents on auto-injector and nasal spray and give [the companies] some reasonable amount of money to reimburse them,” Gupta, now an internist and researcher in Philadelphia, suggested to Filter.

There is nothing preventing the government from doing this right now. It would involve invoking the government patent use statute US Code 28 section 1498, which provides patent immunity to the US government, so long as it provides reasonable compensation to the patent owner, for an invention it intends to manufacture itself.

This way, federal agencies and their contractors could import or produce any formulation they liked, sell it at cost, and simply provide the patent holder with “reasonable and entire compensation.” That could mean something like 10 percent of sales or less—such as when the Department of Defense invoked it to produce patent-violating night vision goggles, or when the Department of the Treasury wanted to purchase patented software.

Another way to address the issue would be to incentivize competition that would, in theory, drive prices down. The FDA appears to be pursuing this. In 2016, the agency stated that it had completed label comprehension studies—a step it had never taken before—to encourage applicants for FDA approval of an over-the-counter (OTC) version.

Pharmaceutical and medical devices entrepreneur Michael Hufford cofounded Harm Reduction Therapeutics (HRT), a nonprofit with 501(c)(3) status pending, with the aim of bringing a nonprofit, FDA-approved, OTC naloxone to market.

“Markets do what markets do,” Hufford said, but Gupta’s chart “shows the system is broken—the price rising as the crisis unfolds.” He wants to see OTC naloxone priced affordably and available anywhere. Favaro, too, sees OTC naloxone as a necessary innovation.

Hufford believes that the for-profit system is vital for innovation in the pharmaceutical industry as developers need to see profit potential to invest in research and development. But—like fellow nonprofits Civica Rx (focused on standard in-hospital drugs that keep landing on the FDA shortage list) and Medicines360 (focused on contraception)—HRT seeks to insert nonprofit, lifesaving, essential pharmaceuticals into the US for-profit landscape (it should be noted that HRT has received funding from Purdue Pharmaceuticals to support its work on naloxone).

Hufford believes the FDA’s 2016 statement indicates that it will fast-track the process, and with biocompatibility studies (to show it works at least as well as the existing product) complete and data in the process of being analyzed, he’s aiming to submit an application this year and to bring the first OTC naloxone to market by 2022. It’s already available over the counter in Canada, Australia, Italy, the UK and the Ukraine. HRT’s would be affordably priced and available anywhere.

“We can sell it as cheaply as possible,” Hufford said.

Once OTC naloxone exists, access barriers specific to individual pharmacies (often unaware of standing orders) should melt away. You could buy naloxone without attracting attention—“Out amongst Band-Aids, like any other consumer product,” as Hufford put it. Certainly, OTC status has proven to be an effective measure for nicotine replacement products, for example, or for emergency contraception. It would also, as Hufford pointed out, mean you could just order naloxone and have it shipped to your home using delivery services like Amazon or others.

Marshall noted that biases against her marginalized and criminalized clients, including racial profiling, make retail and pharmacy access problematic even then. Many marginalized people also lack the internet access or the homes to order delivery. Yet it could still be a major improvement in access.

“If HRT succeeds,” Hufford said, “it’ll really be a systemic fix. It’s like a systemic therapy for the entire US public health system.”

But does competition necessarily result in lower costs? US consumers pay dearly for both health care and medications—including essential medicines—relative to consumers in other parts of the world.

The US also exports relatively expensive solutions for countries whose governments fund many essential medicines: Mundipharma, an affiliate of Purdue Pharma, sells its version of the nasal spray, Nyxoid, for up to around $50 in Europe, New Zealand and Australia. An Australian patient without pharmaceutical coverage might pay around $32 for two doses of it unless they are able to access a special government-funded free naloxone program. By contrast, the injectable version costs just $2 or $3 per dose.

“I’m not sure if the so-called ‘free market’ is necessarily the way to go.”

Another option, popular in many countries, would be an upper limit on the price of the drugs and other essential medicines. In Canada, for example, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board is responsible for following pharmaceutical price trends, setting maximum allowable prices for different patent medications based on a range of established factors, and investigating complaints of price-gouging.

Despite concerns that innovation will be stifled if profit isn’t maximized, France, the UK, Sweden and Germany—four countries with powerful research-based pharmaceutical industries—rely largely on regulation (of maximum prices but also of other aspects of drug pricing) rather than competition to keep drug prices in check. Highly regulated Cuba, too, has a dynamic biotechnology industry that has produced over 100 patents and exported new medicines, including vaccines, around the world.

But price maximums are not seen as politically feasible in the US, Gupta said, meaning that manufacturers can charge whatever they want.

“[Canada] would do it,” Campbell said. “I don’t think [the US] would. They’re not willing to put price caps in.” Still, she wondered whether anything short of that is likely to solve the problem of limited access to a lifesaving drug.

“The affordability issue is a huge issue and getting worse,” she continued. “I’m very fearful that if we don’t get something like what [Michael Hufford’s HRT] is trying to do, the pharmaceutical industry is structured so that price-gouging and shortages mean it’s going to get less affordable.”

“I’m not sure if the so-called ‘free market’ is necessarily the way to go,” Campbell said. “I think something that’s more governed, rather than ungoverned, is the way to go.”

Top photograph via San Francisco Department of Public Health. Middle photograph via Bureau of Justice Assistance. Bottom photo by Kastalia Medrano.

R Street Institute supported the production of this article through a restricted grant to The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter.

Show Comments