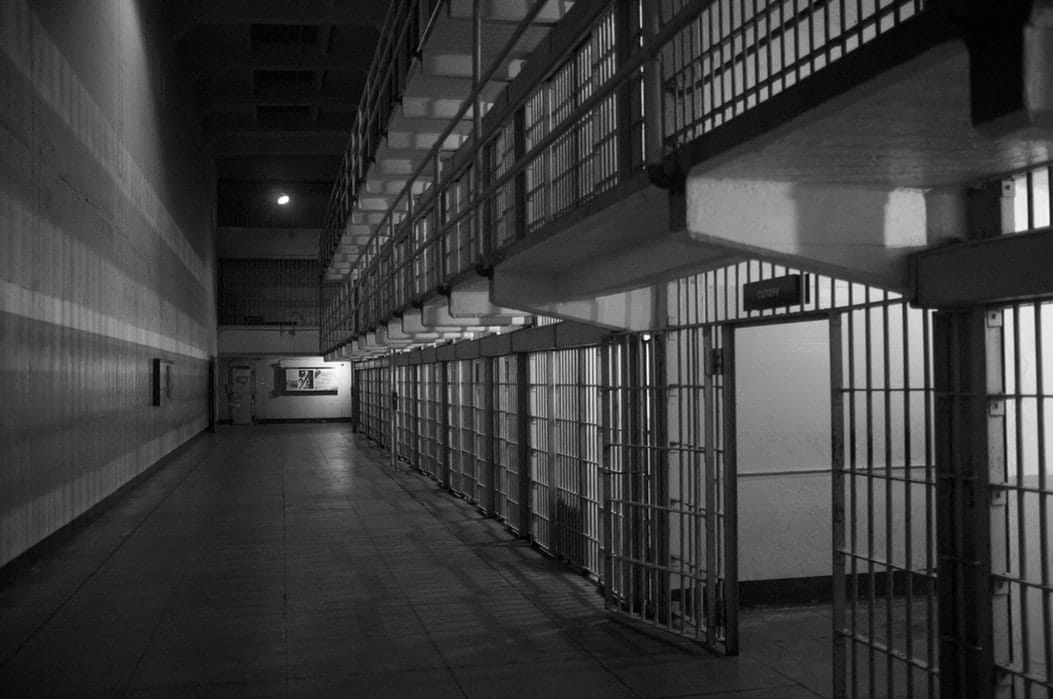

Across the US, there is growing understanding that many local jails are grossly outdated and feature appalling conditions. This when much of their business involves locking up poor people who haven’t been convicted of crimes. It’s welcome, then, that there is potent political activism in cities large and small to shut these jails down.

“We’ve urged counties to look at their jail populations, and find out how many people who are locked up are still legally innocent and just can’t make bail, how many are incarcerated for minor offenses like technical violations of parole, and how many clearly need medical care rather than incarceration,” Wanda Bertram, communications strategist for the Prison Policy Initiative, told Filter. “A lot of people think of jails as necessary evils. So a big part of closing jails is showing that they aren’t necessary, and are in fact doing harm to the vulnerable people who are put there.”

Much of the activism to close local jails comes from people who were themselves previously incarcerated in them.

“Formerly-incarcerated people understand the problems with our justice system first-hand and are the best positioned to provide sound solutions to disrupt the cycles of mass criminalization and mass incarceration,” Brandon J. Holmes, New York City campaign coordinator for JustLeadershipUSA, told Filter. His organization helped to launch #CloseRikers, one of the most prominent campaigns, in April 2016.

“By demanding urgent conditions improvements for people who are currently incarcerated and presenting viable alternatives to incarceration, we are able to rapidly and drastically reduce our over-reliance on the criminal legal system,” Holmes said.

Here is a non-exhaustive round-up of some of the important local campaigns to close jails that are unfolding right now.

New York, New York: #CloseRikers Moves Forward, Pushing for More

In March 2017, amid a prominent #CloseRikers campaign, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced his support for a plan to shut down the Rikers Island complex of facilities, comprising 10 correctional and mental institutions run by the New York City Department of Correction.

De Blasio has emphasized that he believes Rikers is unnecessary because of historically low crime rates in the city, and that it worsens rather than improves public safety. The many human rights complaints against Rikers include its use of solitary confinement.

On October 17 this year, the City Council formally voted, by 36-13, to close Rikers Island by 2026. It also approved an $8 billion plan to build four new smaller jails in Manhattan, the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn. The approved plan requires a reduction of the city’s total jail population by more than half, to 3,300 people, by 2026.

But as the center of political gravity has moved in the direction of #CloseRikers, a new group, No New Jails NYC, has emerged to protest the city’s planned jail expansion. Involving many members of the #CloseRikers campaign, No New Jails is protesting against the use of jails, period.

The group is calling for that $8 billion of city funds to be invested instead in public housing, homeless shelters, public schools and mental healthcare for incarcerated people. The group has drawn support from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY 14).

St. Louis, Missouri: “Close the Workhouse” Wants Nothing Left But a “Vacant Lot”

At the 2019 Reform conference in St. Louise in early November, Inez Bordeaux of of Arch City Defenders, a legal advocacy group, presented about her involvement in the Close the Workhouse campaign aimed at the St. Louis medium-security facility.

“The Close the Workhouse campaign was modeled after #CloseRikers,” Bordeaux said, as a woman from the audience identified herself as having worked on the New York City campaign. “With the exception that right from the jump we said we wanted it to close and not build another jail in its place. […] We looked at the language you used in that campaign and we took it a step further.”

In November 2017, Arch City Defenders (ACD) filed a class action lawsuit against the city of St. Louis on behalf of seven former occupants of the “Workhouse,” which opened in 1966. The suit alleged unsafe and unsanitary conditions at the jail, including overcrowding, extreme heat and cold, lack of adequate medical care, violence and sexual harassment.

The Close the Workhouse campaign has emerged in coalition with ACD, the Bail Project and Action St. Louis. “Burn it down,” said Inez Bordeaux when asked what the facility’s future should be at Reform 2019.

“The Workhouse can’t be saved,” she continued. “It’s a building that should be condemned. It’s infested with rats, roaches, mold, asbestos. It’s going to have to be knocked down. As far as I’m concerned, it can be a vacant lot where we can go and do barbecues.”

The campaign notes that three political entities have the power to close or greatly reduce use of the jail. Firstly, St. Louis Mayor Lyda Krewson could close it by executive order. Secondly, the St. Louis Board of Aldermen could close it by voting on legislation to de-fund it. Finally, St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kimberly Gardner could, in her capacity as prosecutor, reduce the population of the jail—where many people are held in pre-trial detention due to their inability to afford bail. Any of these officials could act today, regardless of what the others decide to do.

Atlanta, Georgia: “Communities Over Cages” Fights to Repurpose and Reinvest

On May 20, the Atlanta City Council passed a resolution to create a task force that will study how it could repurpose the Atlanta City Detention Center and stop using it as a jail. People are detained there for violating city ordinances and traffic laws.

The 25-member task force is working with Bloomberg Associates and an Oakland, California real estate firm to determine what the jail’s future use will be. It is considering ideas such as a health and wellness, job training or mental health center. The task force must deliver its proposal to Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms by February 2020.

Local activist group Communities Over Cages: Close the Jail ATL is continuing to advocate that the $32.5 million the city spent annually on the jail should be reinvested in impacted communities.

San Francisco, California: With Closure Pending, Activists Protest Transfer Plans

In San Francisco, activists and city officials have agreed that County Jail No. 4 must be closed—but disagree sharply over the process and aftermath.

The jail, located on the seventh floor of the Hall of Justice at 850 Bryant Street, is a maximum-security facility. City government has acknowledged that the building is at risk of damage from earthquakes. Other court and law enforcement agencies also housed in the building have already started to move out.

Last month, San Francisco Mayor London Breed announced her plans to move people out of County Jail No. 4 by July 2021. She has proposed relocating them, either to the Alameda County Santa Rita Jail, or to the County Jail No. 5 in San Bruno (along with a renovation). San Francisco Sheriff-elect Paul Miyamoto shares Breed’s intentions of relocating people.

The city previously voted against building a new jail in 2015, wishing to focus instead on reducing its incarcerated population. And the No New SF Jail Coalition is resisting their city’s current plan to build a new jail by 2028, and aiming get everyone out of the unsafe County Jail No. 4 within a year.

“At its core, this campaign is not just about closing 850 Bryant,” said Sam Lew of the Coalition on Homelessness, “but is about reconciling the fundamental racial and economic injustices of jailing by addressing the problem at its root through housing, mental healthcare, and decriminalization […] The jailed population is now potentially the newest group to be displaced out of San Francisco to the East Bay among so many others.”

Los Angeles, California: City Votes to Close Jail, Mulls Jail-Like Mental Health Facilities

According to the ACLU, Los Angeles County, America’s most populated, also has the highest incarcerated population in the US—at a daily average of over 22,000 people.

In February, the five-member Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted to tear down the Men’s Central Jail in downtown LA and build in its place a mental health treatment facility, at a cost of $2.2 billion.

Groups like JusticeLA pointed out the proposed facility, three times larger than California’s largest existing mental health hospital, would be little more than a replacement jail.

The county also considered building several similar facilities under the health department. It is estimated that people with mental health, physical, or substance use disorders make up 70 percent of the county’s jail population.

But on August 13, after months of public outrage from activists, the Board reversed its decision to build the new facility, and voted to instead study how to invest in treatment programs and other alternatives.

Photo by Emiliano Bar via Unsplash.