“The Evolving Field of Opioid Treatment” was the theme of the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence (AATOD) conference, held in Philadelphia in October. But the field has been stuck in a dusty old time capsule since the creation of methadone clinics under the Nixon administration.

How credible were the conference’s promises of evolution toward harm reduction? And what’s behind the change of tone?

Lest we forget, a global pandemic was required to force AATOD, the trade organization for opioid treatment programs (OTP, or methadone clinics), to consider “evolving” harsh clinic regulations that had been in place for over 50 years. COVID-19 had a multiplier effect, compelling the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to update clinic guidelines, and State Opioid Treatment Authorities to re-evaluate their often stricter rules. Mainstream media began to expose the numerous barriers to methadone access, and the New York Times investigated alleged fraud at Acadia Healthcare, one of the largest for-profit OTP chains.

Senator Donald Norcross (D- NJ) proposed the Modernizing Opioid Treatment Access Act (MOTAA), to allow a small group of board-certified addiction doctors to prescribe methadone outside of the clinic system. Norcross lashed out: “We must end the monopoly on this life-saving medicine that only serves to enrich a cartel of for-profit clinics and stigmatize patients.”

For the first time ever, in other words, AATOD confronted the prospect that its methadone monopoly might end. Post-pandemic, frantic cartel bosses had to figure out a way to head off fundamental change while appearing to evolve from a deeply embedded culture of cruelty into “patient-centered care” and “shared decision-making.”

What a difference three years makes! AATOD is no longer panicking. Yet the vibe in the methadone industry has palpably shifted.

In 2022, I attended the AATOD conference in Baltimore. The old guard doubled down to defend the status quo. There was an arrogant insistence that rigid clinic regulations were necessary and no reforms were needed post-pandemic. The biggest focus was (MOTAA) and mobilizing to kill the bill. Jason Kletter, the fear-mongering president of OTP operator BayMark, asserted that pharmacy methadone pick-up was “dangerous” for patients and communities. He dismissed harm reduction principles and practices as “extreme.”

What a difference three years makes! AATOD is no longer panicking. Norcross’s bill is stalled in the Senate, dead for now, and there are no new calls for clinic reform. The media have moved on, amid the Trumpian chaos. Yet the vibe in the methadone industry has palpably shifted.

There was a sense in the workshops I attended that incremental change was needed, and that harm reduction wasn’t extreme. There were even admissions from OTP staff that hinted at the cruelty of clinics.

AATOD President Mark Parrino

John Hamilton, the genial CEO of Liberation Programs in Connecticut, hosted the hot topic roundtable, “Integrating Harm Reduction and Medication Assisted Treatment.” He declared, “With a philosophy of love we can make so much change … It isn’t us versus them.” Hamilton roamed the room Oprah–style, mic in hand, inviting people to share thoughts. One of the most damning disclosures came from Linda Hurley, the CEO of Codac Behavioral Health Care in Rhode Island, who has worked in drug treatment for 30 years and is an AATOD board member. She declared, “We have been paramilitary; no more paramilitary!”

Then Hamilton handed me the mic. I said I was a clinic abolitionist and believed all health care providers should be able to write a prescription for methadone that could be picked up at a pharmacy. I got a round of applause! What? Was I really at the AATOD conference?

The biggest conundrum now for clinics is how to give more take-home medication. Their default position has always been blanket refusal in favor of daily on-site dosing.

But don’t be fooled. Workshops that focused on the “challenge” of implementing new SAMHSA guidelines revealed the true motives for AATOD’s evolution, and they have nothing to do with love.

The biggest conundrum now for clinics is how to give more take-home medication. Their default position has always been blanket refusal in favor of daily on-site dosing, to maintain control over patients in the name of stopping diversion and to protect profits.

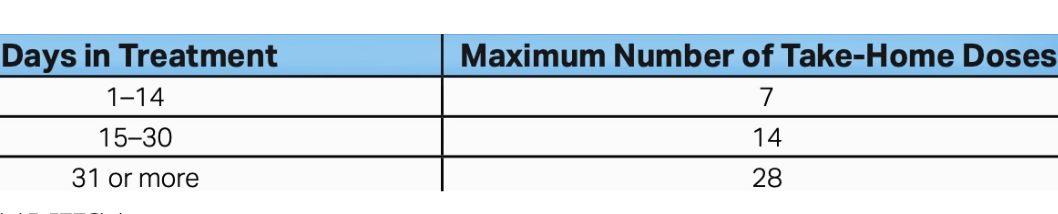

But research conducted during the pandemic irrefutably showed that giving additional take-home medication didn’t result in an increase in diversion or overdose. In 2024, SAMHSA issued a Final Rule making some COVID relaxations permanent—allowing eligible patients to receive up to 28 days of take-homes after their first month of treatment. So there’s pressure to allow more take-homes for patients who meet the SAMHSA criteria.

Image via SAMHSA

But if clinics are reduced to mere bottle-refill stations—grab your month’s doses and dash—how can they maintain the illusion that their on-site services and surveillance justify their methadone monopoly? Why not just let people pick it up from pharmacies?

In one session, Dr. Robert Sherrick, the chief science officer for Community Medical Services (CMS), which owns 70 clinics in 13 states, reviewed changes in SAMHSA’s take-homes policy. He made it clear that the medical director still decides the number of “take-home allowances.” There was no pretense of shared decision-making. “CMS has implemented a triweekly dosing schedule in states where the regulations allow,” Sherrick said, adding that daily clinic visits are still necessary for some patients for their safety.

Triweekly dosing is better than six or seven, but it’s stingy compared to what the Final Rule allows. One of Sherrick’s slides acknowledged that daily dosing is a burden for patients, but so is triweekly. It means patients must continue to make CMS the center of their lives.

The last two points say it all: Clinics should allow some take-homes, to resist further loosening of regulations and avoid losing control as they fight to maintain their survival.

Sherrick explained how staff use SAMHSA’s updated six-point criteria to determine if a patient qualifies for take-homes. These include the absence of serious behavioral problems, problematic substance use or diversion, plus regular attendance and the ability to store methadone safely. These criteria discriminate against certain patients, particularly those who are unhoused. And the way they are wide open to interpretation allows for the denial of take-home bottles for almost any reason.

Random “medication callbacks” continue, Sherrick stated, because, “The DEA likes to see that.” His final slide posed a question:

The last two points say it all: Clinics should allow some take-homes in order to resist further loosening of regulations, stop MOTAA or the pharmacy pickup advocated by the Methadone Manifesto, and avoid losing control as they fight to maintain their own survival.

Another workshop grappled with unsupervised dosing under SAMHSA’s Final Rule. Staff from the Behavioral Health Network (BHN) in Massachusetts described a complicated workflow and assessment tools they’ve developed, which evaluate stability, safety, drug use and factors regarded as protective like having a job, family and clinic attendance.

At BHN, a positive drug test now doesn’t automatically mean a loss of take-homes. This is a positive change. The speakers claimed their decision-making process was based in the philosophy of harm reduction, promoting their tools as a shift from punishment to safety.

But no patients were involved in the creation of these tools, which ignores a core harm reduction principle. And rescinding or reducing the amount of take-home bottles, which remains a central feature of the BHN model, is punishment, no matter how much they reframe it as “safety.”

“Incorporating harm reduction strategies, such as giving out naloxone, doesn’t make you a harm reductionist … It has to include the whole philosophy.”

“Incorporating harm reduction strategies, such as giving out fentanyl test strips and naloxone, doesn’t make you a harm reductionist,” Dr. Kelly S. Ramsey, board certified in addiction medicine and a former OTP medical director, told Filter. “If harm reduction is going to be adopted in clinics, it has to include the whole philosophy of harm reduction, which is about dignity and respect for people who use drugs, and social justice. It’s about incorporating people who use drugs in decision-making … Unless all that is happening, they’re not truly integrating harm reduction.”

The BHN staff and others at the conference naively suggest it’s possible to incorporate harm reduction into the carceral clinic system, with a massive power differential between staff and patients at its heart.

Dr. Ari Kriegsman, the medical director of the BHN clinic in Springfield, asserted, “Take-homes aren’t a privilege, they’re a right.”

So if they’re a right, why is a multi-disciplinary team deciding how many bottles a patient can get? Despite reforms easing some of the harshest regulations some of the time, punishment and coercion are foundational to the system. Take-home “rights” can change or end at any time.

“I get take-home bottles, but that’s because I’m not using drugs now. That would end if I started to use again.”

“I get take-home bottles, but that’s because I’m not using drugs now,” Jerry Otero, a manager at St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction in the Bronx, told Filter. “That would end if I started to use again. Forget the fact that I’m a professional, a responsible dad and stably housed. None of those factors would count.”

“OTPs are a product of prohibition,” he added, “and they can never be compatible with harm reduction or human rights.”

The excessive handwringing around allocating additional take-homes reveals a profound distrust for adults taking methadone without being watched. It’s infantilizing. In no other physician-patient relationship is access to medication subjected to such intense scrutiny and surveillance. When I’m prescribed medication, even an opioid, a multidisciplinary team doesn’t conduct an evaluation to see if I have a job, family responsibilities, use drugs or attend medical appointments regularly.

The handwringing is also about clinics not losing their supposed unique selling point, if all they do is refill bottles. AATOD’s now-defunct Program not a Pill campaign insisted that “medication-assisted treatment” is more than just medicine. Counseling was an absolute necessity, it held, but there was little discussion of that at the conference.

Retention in treatment was a major focus. Studies show that rates are uneven and decrease substantially over time. It’s no secret why: The culture of cruelty erects numerous barriers to both entering and staying in treatment.

What took SAMHSA so long? It’s been known for decades that these rigid regulations result in high drop-out rates.

Several updated SAMHSA regulations can eliminate obstacles if OTPs adopt them. Now, patients can start treatment with 50 mg of methadone or more (it used to be 30), which is more likely to hold people; and split dosing (twice-daily) is allowed without federal approval. Split dosing and the correct dose is particularly important for pregnant patients, as the workshop “The Right Dose Every Day,” led by Dr. Ruth Potee, made clear.

What took SAMHSA so long, especially in the fentanyl era of historic overdose deaths? It’s been known for decades that these rigid regulations result in high drop-out rates. How many people would be alive today if these rules had been in place at the beginning of the overdose crisis?

At the workshop, “Harm Reduction to Increase Patient Engagement and Retention: A Case Study,” Erin Russell, a fierce harm reduction advocate, explained how she trained staff at Behavioral Health Group (BHG) on harm reduction principles and practices.

“I met with the OTP leadership every month and then we did group coaching with the counselors and nurses,” Russell told Filter. “What really made the difference was creating space for people to talk about their hang-ups with harm reduction.”

Apparently the coaching worked. The retention rate at these BHG clinics increased by 15 percent from 2024-2025 according to Tiara Reddick, regional director of operations. Using harm reduction not only boosts retention but increases profit margins, and this is what OTP owners want. Russell said, “Retention rates are an important business metric.”

Her last slide took me by surprise:

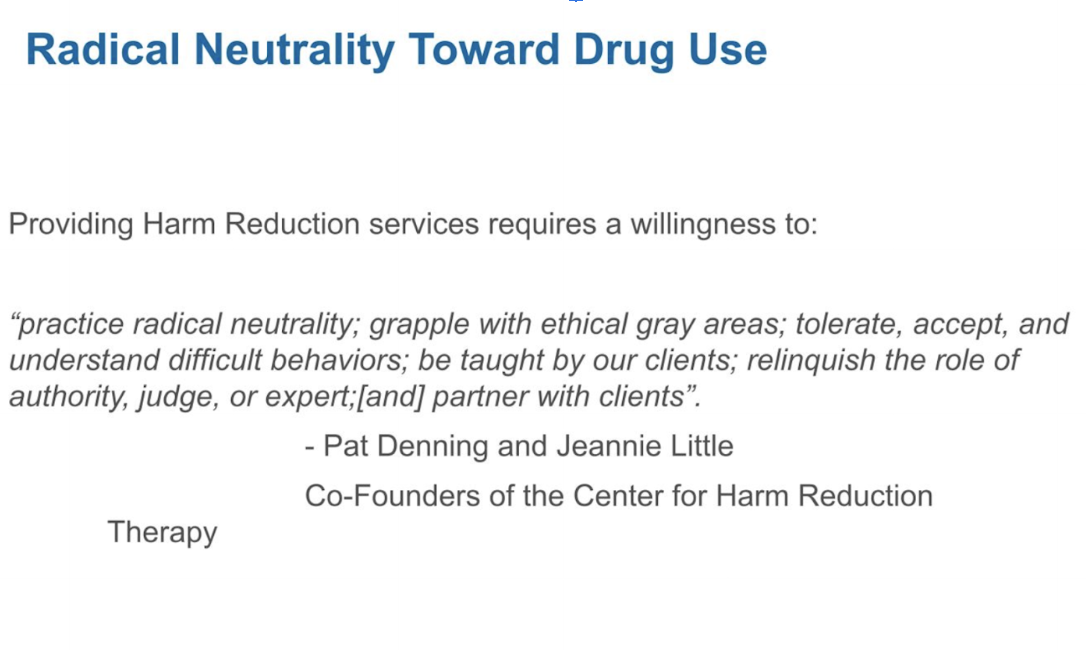

What would Dr. Patt Denning—the harm reduction pioneer and co-author of Over the Influence: The Harm Reduction Guide to Controlling Your Drug and Alcohol Use—think of this whole approach? I asked her.

“It’s always tempting to take whatever improvements you can get, so of course, let’s try to get harm reduction into methadone clinics. But it’s not going to work. The system itself is antithetical to harm reduction, which is about flexibility and choice. The way the methadone clinic system was designed doesn’t allow those two things,” Denning told Filter. “And clinics can’t practice radical neutrality because there are so many rules that patients have to follow or they won’t get their medication.”

This year, there was no DEA agent on the opening or closing plenary of AATOD’s conference, as there usually is. It was time to downplay the drug warriors’ central involvement in methadone clinics—not a good fit with talk of patient-centered care and the principles of harm reduction. Instead, the DEA sent two agents to speak at the AATOD open board meeting. The field of opioid treatment may be evolving, but the DEA is not.

At the closing plenary there was the customary raffle and one of the winners walked away with a portable bluetooth speaker. Then Mark Parrino, AATOD’s forever-president, rose to address the half-empty ballroom. He shared a story about a menacing squirrel who became dependent on methadone. Every day, the rodent ripped open trash bags full of discarded plastic bottles and swallowed the leftover drops of cherry colored liquid.

Parrino explained how the staff tapered it off methadone. If his squirrel story was related to “the evolving field of opioid treatment,” it was lost on me.

Photographs by Helen Redmond

Helen Redmond’s book, Liquid Handcuffs: Policing and Punishment in Methadone Clinics and the Future of Opioid Addiction Treatment, will be published by North Atlantic Books in March 2026. It is available for pre-order here.