I’m proud of my home state of Vermont. We have received some deserved national press in the last two years in recognition of our efforts to curb addiction and drug deaths. The attention that Safe Recovery—Burlington’s syringe exchange program—has received after making Suboxone prescriptions immediately available for almost anyone earlier this year is pleasing.

Except in one regard: Much of the press and official response has glossed over critical elements that make Safe Recovery so precious, and instead used the move to promote an unhelpful way of viewing addiction.

“Recognize addiction as a chronic disease,” urged Burlington Police Chief Brandon del Pozo in a viral Facebook post that made many excellent suggestions, but also called on doctors to “Return the opioid prescribing rate to pre-epidemic levels.”

“Over the past few years, Vermont has built a “hub and spoke” system that has integrated addiction treatment into the broader health care system,” noted a Vox article. “… Things are much better now, [Safe Recovery’s Grace] Keller said, but Vermont’s work is far from done. Case in point: John Brooklyn, one of the architects of Vermont’s hub and spoke system, estimated that around 35 to 40 percent of people in the state who need care for an opioid use disorder have gotten into treatment. That leaves more than half without care they need.”

“With thousands of people now enrolled in Vermont’s “hub and spoke” program for opioid addiction, officials are increasingly focusing attention and resources on the thousands who aren’t,” announced the Vermont Digger. “A new $525,000 federal grant will allow a key opioid-dependence program–Burlington-based Safe Recovery–to directly help that ‘harder-to-reach’ population.” Which is great—except for the implication that Safe Recovery’s other services were not already providing invaluable help.

Such announcements emphasized—some subtly, others less so—a prioritization of narrowly medicalized responses to risky drug use over the broader continuum of harm reduction already exhibited by Safe Recovery.

What Safe Recovery Was Already Doing So Well

Safe Recovery (SR) has been a boon for Vermont’s public health since it opened in 2001. It operates from the purest harm reduction principles. Its doors are open to anyone. It preserves and improves life—including reducing overdose and HIV and hepatitis C transmissions—by providing clean drug injection equipment, medical assistance and naloxone. But it doesn’t stop there.

SR also offers information about available addiction services and makes referrals on request. It refers people in need to housing support and provides assistance with insurance and legal problems, too. Just as critically, SR provides friendly, non-judgmental people to talk to.

In short, Safe Recovery is special because its interventions are grounded in treating people whose drug use may be chaotic and harmful like important human beings with meaningful lives.

Last year, lawmakers—led by Vermont’s State’s Attorney Sarah George—proposed opening a safer consumption space (SCS) in Burlington. A survey indicated that 90 percent of SR’s current clients would utilize one. So Safe Recovery made itself (unofficially) available to host the program in its building. However, the proposal was sadly rejected by the Vermont Senate.

Then this summer, the Burlington City Council introduced an SCS measure. This measure was shelved “until the city council affirmatively votes to do so” (that’s a no), but the council voted 9-3 to promote Suboxone treatment, to be provided by Safe Recovery.

I absolutely support Suboxone access. Studies show that long-term methadone and buprenorphine use has cut mortality in some populations by half or more for people with opioid use disorders. At the same time, the widespread portrayal of SR’s new role carries serious negatives.

Of course, speaking equivocally about any aspect of Suboxone provision is liable to be challenged, and I’ll need to explain myself. So let me contextualize my perspective—as a specialist who works with struggling students and their families, as well as adults with addiction.

Vermont’s Mixed Picture

Vermont is home to many programs that provide strong social and community support. But despite our best intentions, we Vermonters can’t get a handle on our most serious problems. In schools, where I work, clinical diagnoses like depression and anxiety are rising. Meanwhile, drug poisonings and fatalities in Vermont remain at record high levels (the number of overall drug fatalities dropped slightly from 2016 to 2017, while rates of have increased in Chittenden County, where SR is located). Why is that?

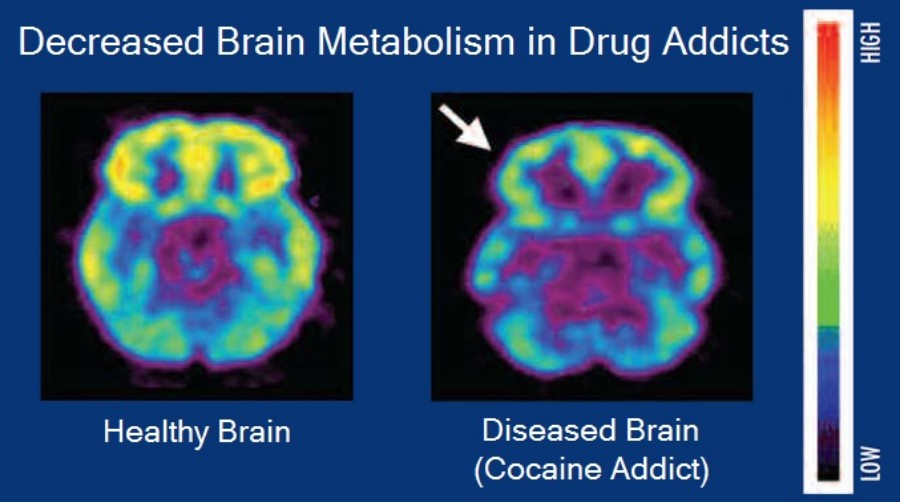

One part of the answer is that Vermont policy-makers—and most Americans—believe in the disease model of addiction (i.e., that addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease). Different versions of the disease model posit that people with addictions must receive special kinds of help—either spiritual, or medical and biochemical. Many of Vermont’s newer policies are largely medical approaches, with an over-assumption that medical solutions are total.

In reality, when a therapeutic setting is helpful, it is nearly always the case that we see basic elements of social support, access to care and community in the setting, with encouragement and opportunities for people to expand their visions of themselves and their life options. There is nothing magical, medical, or out-of-the-ordinary in this—and that should be a source of incredible optimism.

The disease model on which many programs are founded fails to produce desired real-world results. The low success rate of Alcoholics Anonymous is the classic example when we take the spiritual version of the disease model.

Pain pill restriction policies cause unintended harms.

As for the medical/biochemical version, one of Vermont’s policies, aimed at curbing opioid addiction, has been the regulation of pain pill prescriptions—as advocated by Police Chief Brandon del Pozo. The idea that this solution would save lives hinges on the assumption that opioids are inherently addictive. Therefore, fewer drugs will lead to less drug use and fewer addictions.

This may seem logical. But this policy is not working. While national opioid prescribing rates have dramatically decreased since 2010, drug-involved deaths have dramatically increased.

Pain pill restriction policies cause unintended harms. Many chronic pain patients, taking their drugs as prescribed for pain, are now denied access to their medications and suffer with more severe pain than ever. Tragically, some of these patients have ended their lives: either accidentally, after seeking unreliable illicit drugs to replace their prescribed ones; or intentionally, out of despair. Limiting pain prescriptions remains popular in Vermont and throughout the country.

An alternative approach is exemplified by the Chittenden Clinic, which offers methadone and Suboxone, along with therapy and community resources, and is Vermont’s most famous program taking on addiction-related problems (I should disclose that my wife is a clinician there).

I support offering people these drugs, as I’ve said. I know that first, drugs themselves don’t make people addicted, and second, if people crave and seek opioids, it is safer to make them accessible in regulated forms. Many of the clinic’s clients and former clients credit the program and its clinicians for helping them stay alive and on the positive side of life’s balancing act.

The Chittenden Clinic saves lives, not only because it prescribes drugs, but because the clinic’s staff are trained to circumvent clients’ life-problems, including but not limited to addiction.

Harms of the Disease Model

Medications like Suboxone and methadone are effective at keeping people alive. Self-evidently, that’s hugely important. What they don’t do, on their own, is solve the life issues that clients face—we also need life-centered, human interventions to be available to help do that. And we shouldn’t allow our justified support for access to medications to obscure that.

In addition to its negative influence on policies, the disease model carries direct dangers for people who believe in it.

One national illustration of this is that large cities—the areas where MAT is most readily available, are now showing the biggest surge in drug-related deaths, usually from heroin mixtures. That’s not an argument to reduce MAT provision in those places; it is an argument to add more of other kinds of care.

In addition to its negative influence on policies—like Vermont’s pain pill restrictions, or our nation’s perseverance with harshly punitive drug policies, often justified by the supposition that addictiveness is an inherent quality of certain drugs—the disease model carries direct dangers for people who believe in it.

Safe Recovery’s holistic harm reduction values are timeless. Their attention to the everchanging struggles and needs of deprived community members, and their indifference to single addiction models, has long served as a bulwark against failed assumptions and interventions.

While policy makers, public figures, and experts are constantly chasing the next revolutionary addiction “solution,” Safe Recovery is well poised to provide whatever assistance people need. On-the-spot Suboxone is the latest element of that.

A reasonable person could point out—and believe me, I argued with myself in circles about this—that if you agree the drugs ought to be available, who cares why they’re available? Isn’t it the same outcome? Isn’t this just theoretical quibbling?

But I don’t think it is. In addition to its negative influence on policies—like Vermont’s pain pill restrictions, or our nation’s perseverance with harshly punitive drug policies, often justified by the supposition that addictiveness is an inherent quality of certain drugs—the disease model carries direct dangers for people who believe in it.

One famous study, for example, (focused on alcohol) pointed to two factors as “optimally predictive” of relapse: “lack of coping skills and belief in the disease model.” In other words, the innate pessimism of the disease model is self-fulfilling.

In contrast, the services provided so admirably by places like Safe Recovery and the Chittenden Clinic can help people to develop both coping skills and self-empowerment. Safe Recovery’s value and potential is far greater than they have sometimes been credited for. People deserve to know the whole story.

Like this article? As a nonprofit publication, Filter is funded entirely by donations and grants. If you wish to support our work of reporting on drug use, drug policy and human rights, please donate using the button below. We’re so grateful for your support.