[Read Part 1 of this story here]

Fighting is a fact of life in prison. I’ve spent most of the past four decades locked up in one kind of carceral facility or another, and in that time I’ve only met a few people who’ve never ended up in a physical altercation. There are fist fights; grapple fights. When a situation is escalated to a weapon fight, the most common weapon is a homemade knife called a shiv or a shank.

Shanks are made from whatever materials a prisoner can acquire; usually metal, but sometimes plastics like Lexan, or wood. I once saw a metal sword over two feet in length, with a wooden handle. More common will be something like a toothbrush with a razor blade melted into the handle. The other common design is more like a pick than a knife—a small, sturdy metal or plastic bar wrapped with cloth and tape on one end and sharpened at the other.

When it comes to prison wound care, it’s not just the blade itself you’re dealing with. You have to assume that the blade was deliberately contaminated with something intended to cause infection—feces, usually. The point of this kind of weapon is to cause fatal injury, whether the fatality comes during the fight or after it’s over.

The fact that the wound was incurred during a fight means that a visit to medical might increase harm—potentially even new criminal charges. Because of that, peer wound care from other prisoners is often the safer option in the end.

There are generally two approaches to these wounds: packing, for punctures; and suturing, for cuts. The first thing you’ll need to do for either is find a clean surface onto which you can set your materials, whether that’s cheesecloth for packing or a needle and dental floss for suturing. Wipe down the surface with an alcohol pad or hand sanitizer if you happen to have it. Next-best would be hydrogen peroxide. If none of that is available, just wash it with soap and water; don’t use homemade prison liquor. Scrub your hands with soap and water. Wear latex gloves if you can get them. This is a surgical procedure.

Packing

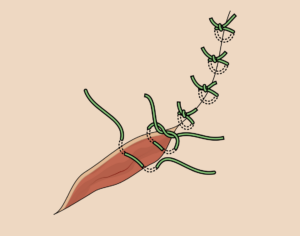

The deep punctures from pick-style blades are the hardest to clean, because of the way the flesh naturally squeezes together at the deepest point. But it’s imperative that all potential traces of harmful bacteria from a contaminated blade be flushed out before you begin packing the wound. Saline in a nasal spray or other type of squeeze-action bottle is the go-to. When you think the wound is completely flushed out, flush it again.

Next you’ll pack the wound with cheesecloth, moistened with more saline. You might need some type of utensil to push it all the way in, like the barrel of a pen. This will hurt, but will help keep infection away while the cheesecloth absorbs the discharge. Sanitize the utensil the same way you sanitized the surface you’ve set your materials on.

Wrap with strips of fabric, or an Ace bandage if you have one, so that the wound is completely covered with no edges left exposed. Change it about once a day.

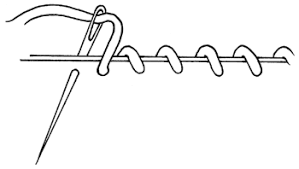

Whip stitch, but make it straight

Suturing

If you’re suturing, a beading needle and unflavored dental floss are often the best materials. When you’re pulling out your floss from its container, make sure it stays clean. Don’t let it drape over nonsterile surfaces; it’s going inside someone. Sterilize your needle with the alcohol or hydrogen peroxide or soap that you’ve been using.

Medical suture needles are curved, which helps them bring the stitch down through one side of the wound and come naturally back up on the other side. Beading needles or whatever else we’re likely using in prison don’t offer this luxury. Nor do we have forceps to hold the sides of the wound together during suturing; just fingers.

There are two main types of stitches you attempt here. The first, a whip stitch, is the easier one. It uses one continuous piece of floss, so put a lot on the needle—you don’t want to get halfway through and run out.

Each time you poke the needle in to begin a new stitch, don’t close the wound by pulling on the floss itself; use your fingers to feed it through. Tugging on the floss is likely to break it or make for puckering and uneven closure.

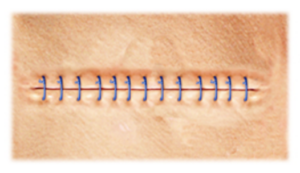

Suture stitch

The second type of stitch is an interrupted suture stitch. This is more difficult, but done properly makes for a less puckered scar. Rather than one long piece of floss, each individual stitch is done with its own separate piece. This means you have to tie a knot for each stitch, tight enough so that it doesn’t slip out. The knots are what make this the harder option.

Placement of the stitches is important. Too close to the wound, and they’ll tear out. Too far, and they’ll pucker. Try to stay about 3/8 of an inch away from each side of the opening. When pulling the floss through, use your fingers to press the two sides together. Slide the floss through gently; pulling too hard will rip it. Don’t go too deep—keep it to about 1/8 of an inch, just enough to pull the top layer of flesh closed.

Actual medical professionals would be able to do a tidier job, but for our purposes we just need a straight, sturdy stitch that won’t tear or fall out or cause more harm. That’s all you’re trying to do here.

This article is not medical advice.

Top photograph via Office of Justice Programs. Second image via City of Lafayette, Colorado. Third image via National Library of Medicine. Fourth image via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 1.0.

Show Comments