Nearly 13 months since the first coronavirus relief bill was signed and nearly three months since the inauguration of a new president, Michael Scebbi still hasn’t received a stimulus check. His ability to reach the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) from his cell in Ohio’s Trumbull Correctional Facility is limited. His girlfriend has waited on hold with the IRS day after day, sometimes for three hours at a time, but only ever reaches an automated message or representatives who say they can’t help.

“I don’t have a clue as to what else I can do next to see if I’m filed and approved to get the EIP checks,” Scebbi told Filter via JPay, an electronic messaging system used in incarceration facilities.

After the passage of the third stimulus bill, some Republicans decried the idea of incarcerated people would receive checks, even though the first two stimulus plans also included payments for prisoners. Despite the change in presidency, the IRS commissioner has not changed. For incarcerated people and their families, the process of stimulus payments remains a byzantine affair. (The White House did not respond to Filter‘s request for comment.)

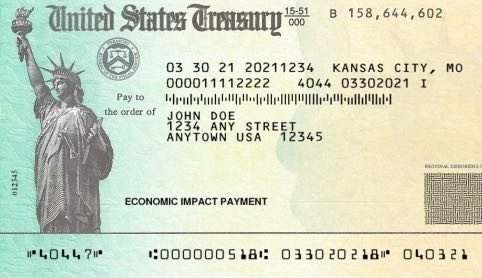

Across the country, incarcerated people and their loved ones have been left wondering about the status of their stimulus payments. After initially distributing 950,000 stimulus checks to incarcerated people in spring of 2020, the IRS then ordered those who received those funds to return them, prompting a class-action lawsuit.

In September, a district judge ordered the IRS to send funds to incarcerated people and tax forms to prisons. But an arbitrary deadline imposed by the agency left activists little time to inform prisoners that they were eligible.

As activists flooded prisons with 1040 tax forms, needed by many to file for their stimulus check, the prisons rejected the paperwork. Though the IRS also sent carceral facilities stacks of 1040s, as required by the judge, incarcerated people didn’t always have enough time to fill them out and postmark the forms by the November 4 deadline. Some managed to meet the deadline only to have the IRS fail to process their payments anyway.

“I think a lot of them assume there was identity theft because they never heard anything from the IRS.”

“There is no verified public number” of how many incarcerated people haven’t even received their first stimulus checks, despite filing necessary paperwork, Kelly Dermody, a partner at Lieff Cabraser, Heimann & Bernstein, the law firm that brought the class-action suit, told Filter. Dermody said a Congressional office looking into the issue told her that the IRS hadn’t processed 70,000 claims submitted by incarcerated people to receive the first stimulus check.

“Many never got their first and second [stimulus] so they have to file a form to track down their check or many just want to file an identity theft form,” Margaret Breslau, co-founder of the Virginia Prison Justice Network, told Filter. “I think a lot of them assume there was identity theft because they never heard anything from the IRS.”

Breslau and activists from other states said that prisoners have received letters instructing them to call a central IRS line and verify their identity. Hefty fees and limited phone time prohibit prisoners from actually reaching a representative.

“There may not always be perfect solutions available. We’re trying our best to offer a range of solutions,” an IRS spokesperson told Filter, adding that the agency is conducting outreach to ensure that eligible people receive their checks. “If there are gaps, we need to figure out a way to address those.”

Prisoners who did receive the payments often discovered that their first stimulus check had been heavily garnished, as the quickly drafted CARES Act did not prevent states from swiping hefty portions of the money.

People who didn’t receive either of the first two stimulus checks were instructed to request the payments on their 2020 tax returns. Unlike after the class-action suit, however, the IRS was not required to send tax forms to prisons. Activists had to begin outreach efforts once again.

“Family members are still making the hard decision about whether to take funeral costs or have loved ones buried in the prison cemetery.”

Azzurra Crispino, the co-founder of Prison Abolition Prisoner Support, tried sending her incarcerated husband 100 tax forms through the IRS website. Instead of the forms, the agency sent a postcard stating the IRS would not fill document requests from correctional facilities.

“In 2012 the IRS changed the practice of filing tax product orders for inmates of correctional facilities,” an IRS spokesperson told Filter. “Due to an increase in orders that appear to be frivolous requests and the increase in these orders being returned from prison facilities because they are deemed contraband, the National Distribution Center (NDC) will no longer fill orders they can identify as coming from an inmate.”

The spokesperson said that prison resource officers or prison officials could receive the forms, or that incarcerated people could find the forms in facility libraries—recommendations that are not always practical due to pandemic lockdowns.

Crispino said that the IRS sent 100 tax forms to one Ohio facility, but the prisoner who received them was written up for contraband and the forms were destroyed. (The Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction did not immediately comment when asked about policies regarding blank tax forms.)

As prisoners and their loved ones on the outside try to reach the IRS, activists said their expenses have increased during the pandemic.

“People are still dying. Family members are still making the hard decision about whether to take funeral costs or have them be buried by the prison in the prison cemetery,” Crispino told Filter.

“My husband is continuing to say that the food he’s getting isn’t sufficient, so I’m continuing to send him more money in commissary and more food packages. Our phone bills continue to be through the roof.”

Photograph via Internal Revenue Service

Show Comments