Congressmembers are pushing for new laws that will impose harsher penalties for potent synthetic opioids like fentanyl, which are involved in tens of thousands of deaths in the US each year. Various pieces of legislation propose to classify fentanyl analogues as Schedule I narcotics, for example, and to increase mandatory minimum sentences for even small amounts of the drug. But adopting such federal laws will likely increase racial disparities in drug arrests, lead to more dangerous substances being used, and fail to reduce deaths.

These are some key takeaways from a report released by the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) on January 22. Titled “Criminal Justice Reform in the Fentanyl Era: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back,” the report analyzes 39 US states that have already increased fentanyl penalties. Comparing current fears of fentanyl to the crack cocaine panic of the 1980s, it finds that these new laws only result in more people who use drugs being criminalized and jailed—with no reduction in deaths.

The researchers recommend that governments instead support harm reduction-oriented approaches like 911 Good Samaritan laws, medication-assisted treatment and safe consumption sites.

“We experience drug panics here in the US every few years, with increasing media and press attention,” Dr. Sheila P. Vakharia*, deputy director of DPA’s Department of Research and Academic Engagement and a co-author of the new report, told Filter. “We talk about the ‘new drug of the week’ being more lethal and dangerous than what we’ve seen before. We’re in this phase now with fentanyl, but we’ve been here before with K-2 and ‘bath salts.’ It’s incumbent that we’re all aware of what happens when we make exceptions for whatever new drugs emerge on the scene.”

The report explains how the US Sentencing Commission (USSC), which sets federal sentencing guidelines, has voted in recent years to effectively reduce sentences for most drugs. The USSC has argued that this is necessary to alleviate a crowded federal prison population. But in 2018 the body voted to increase fentanyl-related penalties, citing “the severe dangers posed by fentanyl.”

DPA studied USSC data representing 51 of the 52 federal fentanyl trafficking convictions in 2016. Half of the individuals were identified as Hispanic, while one quarter were Black—illustrating that as with other drugs, fentanyl prosecutions target people of color.

Additionally, over 25 percent of the defendants were “couriers or mules,” and over 23 percent were “street-level sellers.” This shows how harsher fentanyl penalties mostly target people lower in the supply chain, rather than so-called “kingpins.”

Altogether, the number of people convicted for fentanyl trafficking increased eightfold between 2016 and 2018. The average sentence in these cases was five-and-a-half years in prison.

DPA found no evidence that these changes have reduced drug-related deaths or the supply of fentanyl.

Examining the 39 states (and the District of Columbia) that have increased fentanyl penalties in recent years, DPA found no evidence that these changes have reduced drug-related deaths or the supply of fentanyl. In addition, the report suggests, these laws may be encouraging drug manufacturers to develop new substances to avoid heightened punishments. These new substances are chemically similar to fentanyl but may be even riskier, potentially leading to more deaths.

Harsher punishments for fentanyl also impact people who use other drugs. “The reality is that much of the heroin in the East Coast and Midwest of the US already contains fentanyl,” the report states. “Increasing penalties for fentanyl, therefore, will simply end up increasing penalties for heroin and contribute to more incarceration.” As Filter has reported, fentanyl is also being found in supplies of drugs like methamphetamine and cocaine throughout the US.

The report’s recommendations include that governments should strengthen 911 Good Samaritan laws. These encourage people to call for help when witnessing an overdose by protecting them from criminal prosecution; cities and counties can then treat fentanyl overdoses as the medical emergencies they are, rather than crime scenes.

Another effective strategy that jurisdictions can adopt is increasing the availability of, and training in, naloxone. Police and first responders are increasingly carrying naloxone throughout the US. But drug users’ friends and loved ones are often the first to witness an overdose, and equipping them represents the best chance of saving lives.

The report supports further harm reduction interventions, such as opioid use disorder treatment with medications like methadone and buprenorphine and the introduction of heroin-assisted treatment, improved drug checking services and data collection on illicit drug sources, and safe consumption sites.

But in order for these measures to work, they have to meet different populations’ unique needs. “We are seeing fentanyl-related deaths increase in Black urban centers along the East Coast and Midwest,” Vakharia said. “This means we need to target our harm reduction efforts to make them equally accessible and culturally competent to different populations. We need harm reduction workers from impacted neighborhoods to be the people delivering those services.”

For now, the federal government can improve access to harm reduction primarily through grants and funding. But even absent any federal action, local governments can make the biggest changes that will save people’s lives.

“Cities and counties can support harm reduction programs either by staying out of the way, or collaborating with existing services,” Vakharia said. “They can allocate public health funding to help more people get trained to use naloxone. Law enforcement can respect Good Samaritan laws by not criminalizing people using drugs, and we can expand access to opioid-assisted treatments through jails, drug courts and treatment providers.”

*The Drug Policy Alliance has provided a restricted grant to The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, to support a Drug War Journalism Diversity Fellowship. Dr. Vakharia is a member of the board of directors of The Influence Foundation.

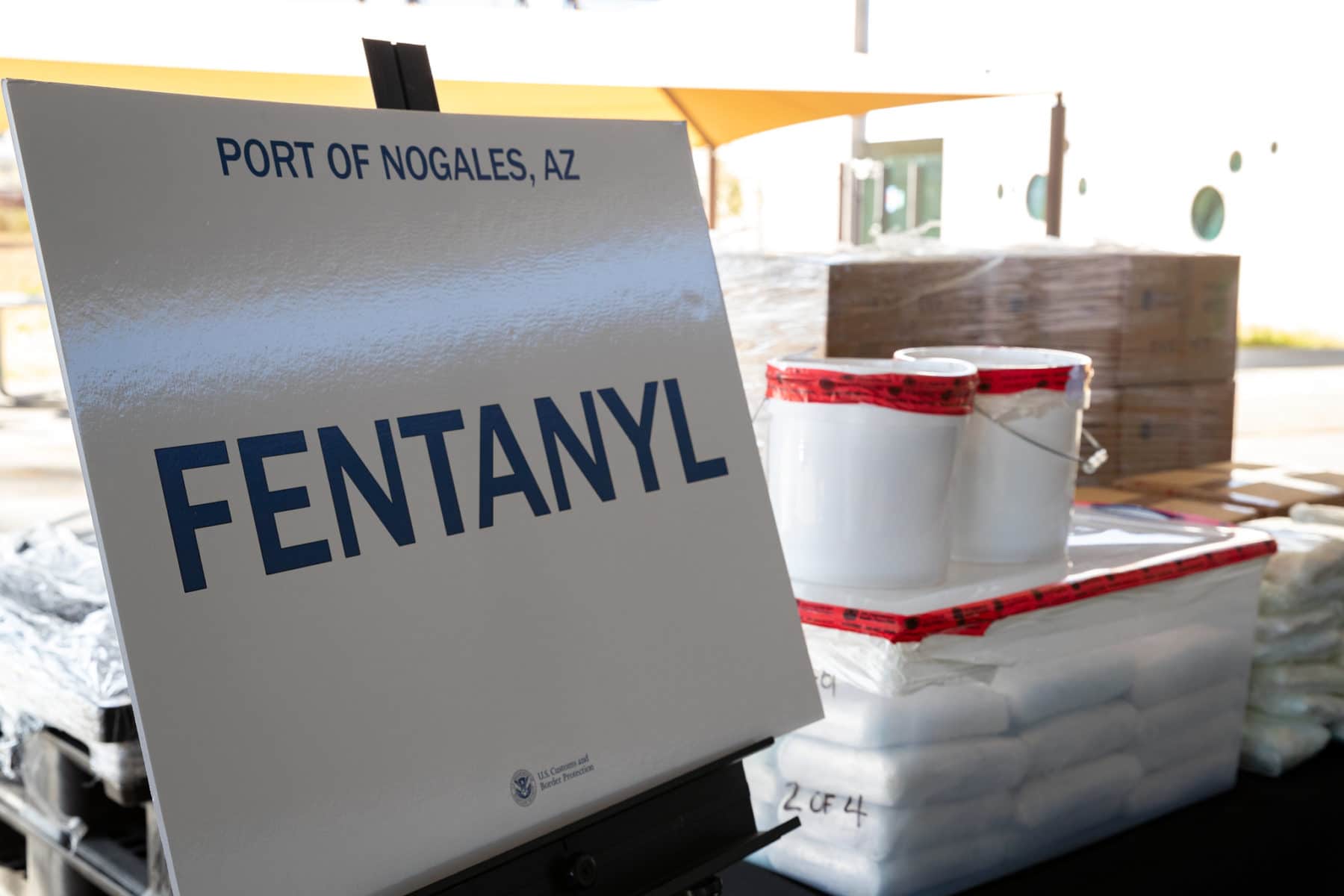

Photo of fentanyl seized in Arizona by US Customs and Border Protection via Flickr.

Show Comments