Public education campaigns about drugs often rely on ineffective and stigmatizing scare tactics. They spread fear and shame that make people who use drugs feel more isolated and more hesitant to connect with treatment and support services. A different approach to public health messaging is needed—one that embraces harm reduction. With “Go Slow,” a prominent campaign that launched in July 2019, Baltimore now has such an approach.

The overdose crisis has devastated the whole country, but Baltimore has been hit especially hard. Unlike the mostly white rural communities that have gotten so much attention in recent years, majority-black Baltimore has been grappling with high rates of opioid use for decades. The city’s high rates of substance use are driven by disparities in the social determinants of health—the direct result of a long history of systemic racism and inequality.

The recent saturation of the drug market with fentanyl has only compounded the existing crisis. There were nearly 800 overdose deaths in Baltimore in 2017, four times the amount in 2011. Over 75 percent of the fatalities involved fentanyl.

“People really know who we are. They trust us and know we won’t talk down to them.”

In Baltimore, Bmore POWER (Peers Offering Wellness Education and Resources) is on the ground spreading hope and saving lives from overdose every day. This peer-led group of harm reductionists provides education and resources in the neighborhoods most impacted, such as Sandtown-Wincester and Lexington Market. Most members of Bmore POWER have lived experience with drugs and are from the communities they serve.

“People really know who we are,” said Bmore POWER member Montressa Tripps. “We go where nobody else will go. We’re on the street, in the alleys and in the shooting galleries. People will come out of vacant houses when they see us and ask, ‘Can I get one of those [naloxone] kits?’ After getting naloxone they’ll often ask, ‘what else can you help me with? Can you help me find treatment? Get social services? Help me find a way for my child to go to school in a safer place?’ They trust us and know we won’t talk down to them.”

When fentanyl entered the drug supply a few years ago, Bmore POWER members started to see a startling trend: a sharp increase in overdoses among experienced drug users who had been using heroin for decades. In 2017 Bmore POWER member Pheadra Ward was heartbroken to see the deadly impact on her friends and community. She wanted to create a public education campaign to warn people and save lives.

Bmore POWER partnered with Behavioral Health System Baltimore (BHSB) and the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (CCP) to figure out how to make Phaedra’s idea a reality.

I work at BHSB and have been collaborating closely with Bmore POWER. We wanted to create a public education campaign about fentanyl to get useful information to the people most at risk. No one has a better understanding of the risks of fentanyl than the people with recent or current lived experience with it. We decided that they should lead the development and design of the campaign.

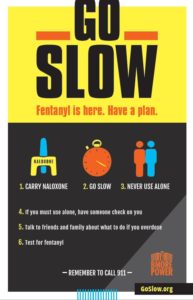

The message is deliberately simple: “Go Slow. Fentanyl is here. Have a plan.”

So Bmore POWER, BHSB and CCP facilitated a three-day brainstorming session with Bmore POWER members and other peers and people who use drugs. It was set up like a “hackathon,” tapping shared knowledge to help participants come up with innovative ideas.

“Because of their lived experiences and grassroots work in the community, Bmore POWER members are experts in what resonates most with people at risk of overdosing on fentanyl,” said Amber Summers of CCP, who facilitated the hackathon with her team. “That’s what made them crucial to the campaign development process, helping to generate messaging ideas and design campaign prototypes.”

The “hackathon”

Once the main concept for “Go Slow” was developed, we partnered with a local design firm, Mission Media, to develop the visual materials for public display and the website.

The campaign is focused on giving people who use drugs practical, actionable tips to reduce the risk of fatal overdose. The message is deliberately simple: “Go Slow. Fentanyl is here. Have a plan.”

The Go Slow campaign includes ads on Baltimore mass transit, online and on social media across the city. Bmore POWER members give out Go Slow materials with naloxone during outreach. The campaign outlines six practical tips: 1. Carry naloxone, 2. Go slow, 3. Never use alone, 4. If you must use alone, have someone check on you, 5. Talk to friends and family about what to do if you overdose, and 6. Test for fentanyl.

The suggestion to test for fentanyl is one thing that makes Go Slow stand out from other harm reduction campaigns. Bmore POWER has also been distributing testing strips during outreach to meet growing demand. Using the strips is a key part of the careful approach to using drugs that Go Slow advocates.

One community member summed it up as: “Be careful, if you have to use. We love you. Be careful.”

In addition to giving out actionable harm reduction tips, Go Slow respects the dignity and autonomy of people who use drugs. We recognize that if people can take steps to protect themselves and their friends from overdose, they will.

Bmore POWER member Roland Brandon has been pivotal in getting the message out. “Go slow is about showing people we really care,” he said. “They need that. When I go out there, people say ‘Y’all really care about us.’ They have given up but now they know that we care about their lives. And I do. I’m out here trying to help because I care.”

Roland Brandon

Feedback from people served by Go Slow indicates that its message is coming across. Bmore POWER asked people in the communities they serve what their perception of the campaign was. One community member summed it up as: “Be careful, if you have to use. We love you. Be careful.”

The campaign is for both people who use drugs and the family and friends who care about their safety. It encourages people to create an overdose prevention plan, which helps to bring the conversation about drug use and overdose into the open. Many people care about someone who uses opioids but feel powerless to help if that person isn’t interested in treatment. They are desperate for anything that will prevent another loved one from dying. Go Slow empowers them to be proactive about it.

It’s not about prevention of drug use; it’s about valuing and saving the lives of people who use drugs.

Takeya Brittingham has worked with Bmore POWER for years, and for her the work is personal. “We have lost so many people to overdose it’s mind-boggling,” she said. “Hopefully we can really get the Go Slow message out there. Maybe there won’t be so many lives lost if people really take the message to heart.”

Takeya Brittingham

Takeya Brittingham

Go Slow is entirely different from conventional “just say no” campaigns. It’s not about prevention of drug use; it’s about valuing and saving the lives of people who use drugs.

This does not encourage drug use, as some critics say. Fentanyl is deadly and the campaign doesn’t minimize the danger. Instead, it fully acknowledges the danger but insists that doesn’t mean people have to die.

By focusing on practical harm reduction tips rather than trying to scare people into treatment, Go Slow shows respect for people who use drugs by meeting them where they are. Almost everyone’s life has been impacted by overdose; many of us have lost people we love due to fentanyl. We believe the Go Slow campaign will help us protect the health and lives of people we care about.

All photographs provided by Behavioral Health System Baltimore