Go slow. Don’t use alone. Always have naloxone.

This is the advice we’re supposed to give people when their dope tests positive for fentanyl. It’s also great advice if it somehow doesn’t have fentanyl, which is why harm reductionists have been saying it for years, regardless of whether anyone had fentanyl test strips.

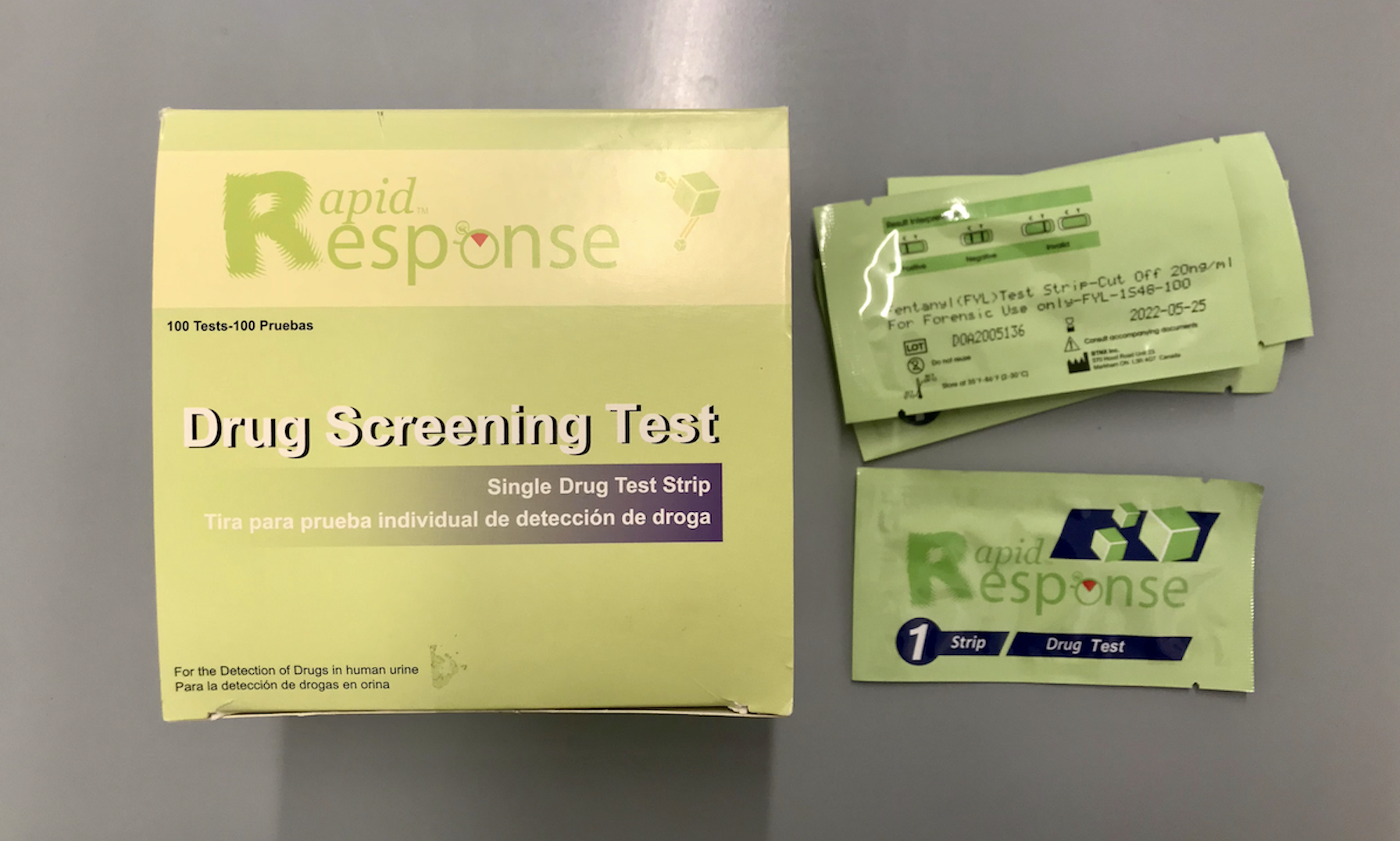

There’s a lot of hype right now around FTS, the $1 rapid drug-checking tool that simply reveals whether or not a sample contains fentanyl. They certainly have a place in overdose prevention, but how often are they really telling us anything new?

Opioid-naive people are not generally the ones being told to use FTS, but they might be the ones who could actually use them.

“We already know that our dope has fetty in it,” said participants at our mobile syringe service program in Greenville, South Carolina, when I posed this question.

That’s the sentiment among many people who rely on illicit opioids where fentanyl has taken over the supply. There are of course many opioid users who want the certainty that comes from physically seeing a sample test positive, and for whom FTS represent bodily autonomy.

But what about other people who use drugs, the ones who rely on stimulants or just use illicit drugs occasionally? Opioid-naive people are not generally the ones being told to use FTS, but they might be the ones who could actually use them.

Imagine a teenager trying heroin for the first time, or someone picking up cocaine for a party. They aren’t staring down withdrawal, or resigned to the reality of having no safer alternative. A positive FTS means more to someone who isn’t expecting it. Someone opioid-tolerant gets the choice of fentanyl or withdrawal, and faces harm on both sides. Someone opioid-naive gets the choice of fentanyl harms or no harms at all.

Making FTS available in high schools would require conversations about drug use that are more open and honest.

But making FTS available in high schools would require conversations about drug use that are more open and honest than what’s currently mainstream in our culture. School boards, like addiction treatment programs and health departments and churches, usually have an abstinence-based philosophy rather than a harm reduction one. They therefore object to something like FTS on principle, because acknowledging them would mean acknowledging that teenagers use drugs.

We educate teens on how to safely drive a car, and in at least some places how to safely have sex. We educate them on safe alcohol use through established social norms that match the consumption to the setting. Bloody Marys at brunch, a few beers while watching a game on TV, wine with dinner—these are all learned behaviors that subtly moderate alcohol consumption and encourage non-problematic use. Alcohol was once prohibited, and we’ve seen how much safer it is to acknowledge it instead.

South Carolina does not have authorized syringe service programs. But in 2021 when such programs were authorized to purchase FTS using their federal funding, the state approved certain organizations to distribute FTS as well as illegal “paraphernalia”—cookers, cottons, alcohol pads, sterile waters—despite no change in legislation.

If the state can suddenly use federal funds to purchase harm reduction supplies without waiting to legalize them, why didn’t it happen years ago?

Photograph by Kastalia Medrano

Show Comments