As the presence of illicit fentanyl has reached near-ubiquity in many North American heroin supplies, some harm reductionists have questioned the utility of drug checking as an overdose prevention strategy.

But even if drug users are assuming fentanyl is cut into their bags, some still find testing strips to be a source of empowerment and agency, according to an International Journal of Drug Policy study published on August 5.

In Baltimore, Maryland, 20 people who use opioids spoke with researchers from Johns Hopkin University about the role test strips play in their decisions to use and purchase “dope”—a term they used to refer to both fentanyl and heroin, highlighting the former’s prevalence in the latter.

In 2016, over 100 Baltimore injection drug users participating in another study (or half of all interviewees) reported that they believed their supply was laced with fentanyl. In the years following, between 2016 and 2018, fentanyl-related overdose deaths in the city leaped three-fold.

Avoiding a batch testing positive for fentanyl is one practice informed by test strips, and some public health officials would like to make that the only use. Dr. Elinore F. McCance-Katz, assistant secretary for mental health and substance use at the federal agency SAMHSA, paternalistically warned in a blog post that people will still use drugs testing positive for fentanyl, calling them unable to make “rational choice[s].”

Some of the Baltimore interviewees in the latest study in fact developed a preference for fentanyl because of their financial constraints—fentanyl’s potency providing more bang for their buck—and the perceived impracticality of finding heroin without fentanyl.

Dr. McCance-Katz, in her blogpost, effectively dismissed drug users’ agency, with or without testing strips. But the recent Baltimore interviewees shared experiences that suggest the contrary.

Test strips empower interviewee Fiona, for example, a Black woman who, the researchers wrote, “enjoys the effects of fentanyl,” to manage the potential social and legal implications of its use. They afford her a sense of control over her own privacy, something often deprived of drug users: “I’d rather be home, or I’d rather be somewhere where I know I can act a fool without anybody seeing me,” she said.

Additionally, choosing when to use a fentanyl-positive batch can defend her from carceral laws: “I don’t want to get some [fentanyl] and know I got to go to court and get up in front of the judge and be cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs. Then I know I’m not coming home,” she said.

“In a context where fentanyl presence is assumed, [fentanyl test strips] not only promote safer drug use practices that can reduce overdose and mitigate other medical harms, but it also provides individuals with reliable and timely information that can support their ability to choose when, where, and what drugs they use to make court appearances, family events or appointments with service providers,” Noelle Weicker, a study co-author and senior research program coordinator Johns Hopkins’ public health school, told Filter.

Another woman of color, Ophelia, used the test strip results to assess the trustworthiness of drug sellers, a quality that can potentially contribute to overdose prevention. In the case of a dealer who sold her a bag claimed to contain fentanyl yet testing negative for it, Ophelia was able to refuse to purchase a product that wouldn’t meet her bodily needs, or as she said, that was not “going to get [me] well.”

Raising awareness was another key result of fentanyl test strip utilization in a saturated market. Some of the respondents who ended up using their fentanyl-positive bag spread the word among their networks about its contents. Others who hadn’t used the test strips themselves reported hearing the results from peers, and then passing the information along. Ophelia, herself, offered her dealer test strips “to make sure you don’t lie to nobody else.”

Weicker sees test strips as a means of engagement for harm reduction workers with their clients. They can be used “to teach individuals not only what [fentanyl test strips] are and how to interpret the results, but also to inform people on the range of ways to use the information. Harm reduction workers should emphasize that with [fentanyl test strips] individuals can choose if, when, and where they use fentanyl, as well as promoting safer consumption practices.”

One interviewee expressed some skepticism about the limits of the strips. In particular, said Chris, a white man using a researcher-given pseudonym, he wished drug checking technology was easily available for assessing “how much fentanyl is in it,” “if it had other crap in it, like carfentanil or ketamine,” and “if it has a variety of the different kinds of crap that people put in it nowadays.” “I think that would be more helpful,” he said.

He’s far from the only person who uses drugs who thinks this. A large majority, about 85 percent, of 300-hundred plus drug users from three East Coast cities, including Baltimore, said they were interested in being able to check for “the amount of fentanyl” and the presence of other substances,” according to a 2017 study co-authored, in part, by Dr. Susan Sherman and Ju Nyeong Park, two of the eight Johns Hopkins researchers from the 2020 study

Weicker agrees with the sentiment. “These findings support the development and dissemination of more comprehensive drug checking services that convey more detailed information about fentanyl and other drugs while maintaining the low-barriers provided by take-home harm reduction tools.”

Other harm reduction responses to fentanyl-positive drugs include first doing a “tester shot” or small injection; using slowly (a tactic championed by Baltimore drug user activists themselves); using with others; and carrying the overdose-reversal medication naloxone.

The Baltimore interviewees’ approaches were “creative,” “unique,” and “unexpected, the scientists described, demonstrating drug users’ emerging practices for defending themselves.

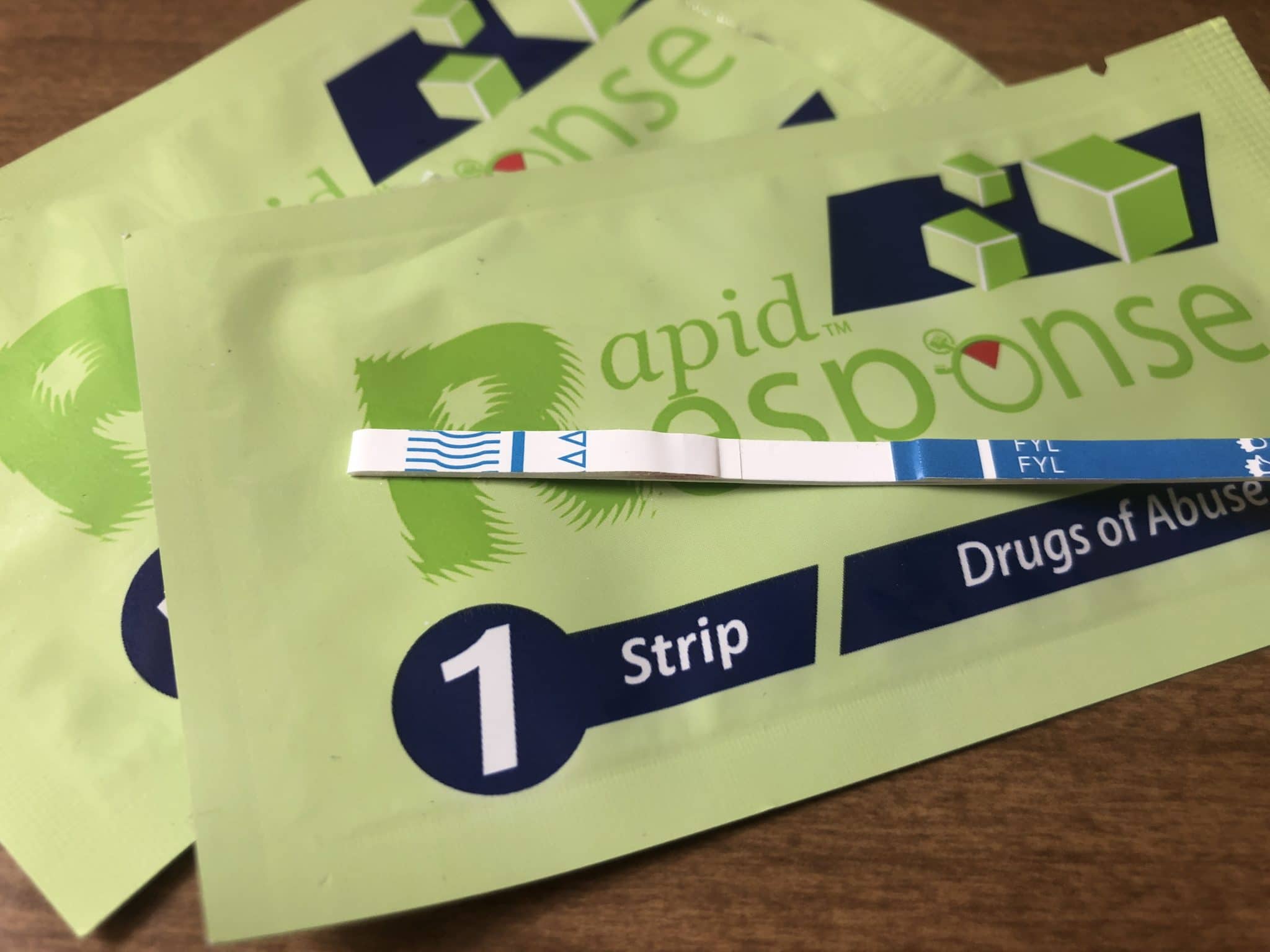

Photograph of fentanyl testing strips by Filter.