As the pandemic sweeps the country, overwhelming intensive care units with patients in need of emergency respiration, medical-grade fentanyl is urgently needed. But supply is limited by reductions in production that were mandated by the the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in recent years, raising concerns among healthcare workers, manufacturers and federal agencies.

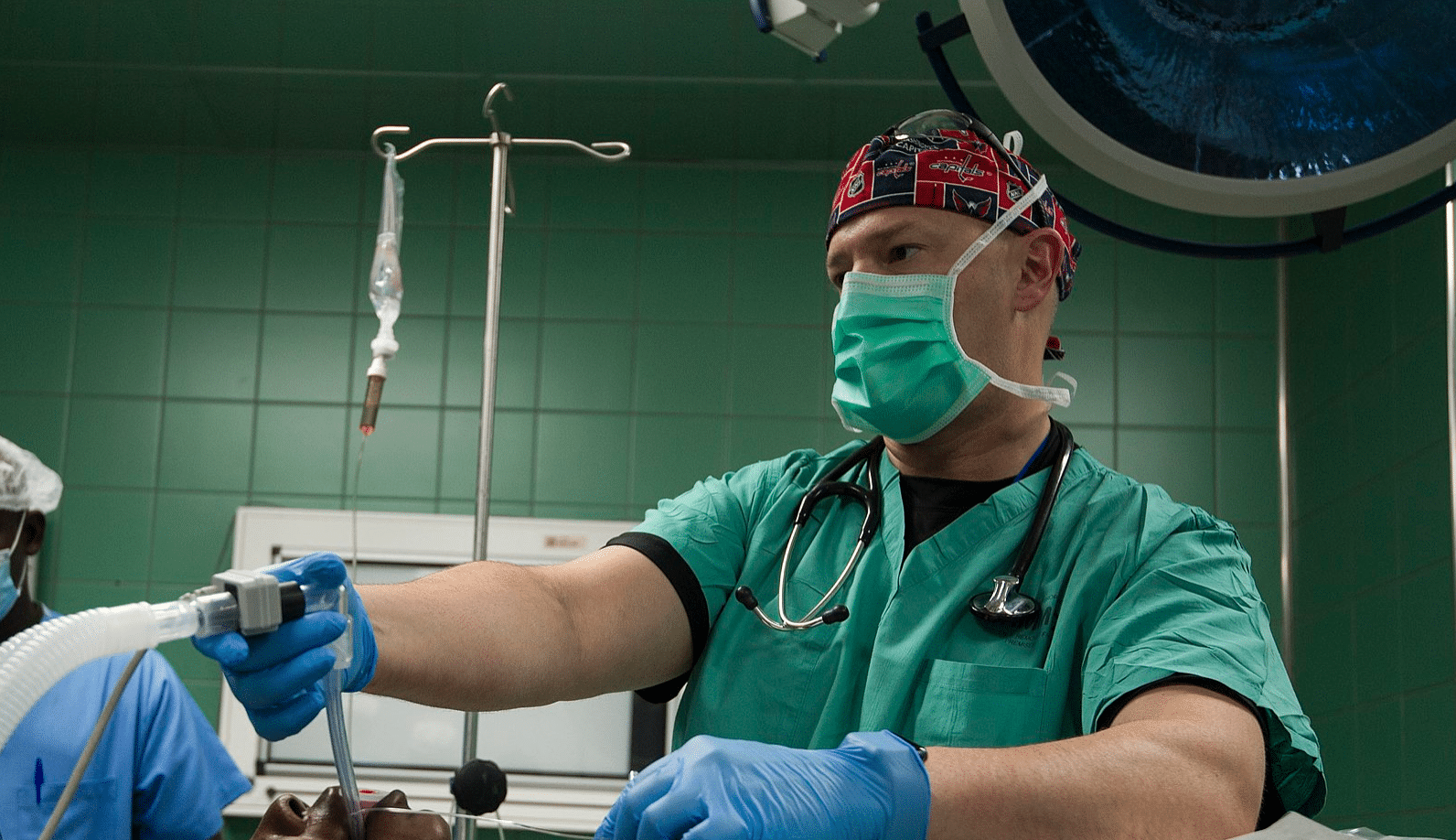

Fentanyl is a key drug for clinicians to administer to COVID-19 patients in critical condition. Doctors from Wuhan, China—ground zero of the coronavirus—recommend using fentanyl when intubating, or inserting a tube into the patient’s airway, in order “to suppress laryngeal reflexes and optimize the intubation condition,” they wrote in a March 26 Anesthesiology article.

On April 10, the DEA increased the cap—or aggregate production quota (APQ)—on pharmaceutical production of fentanyl to ensure companies can supply coronavirus responders with the medications they need. A DEA spokesperson told Filter that the APQ increase “was done out of an abundance of caution, not because we believed the supply was insufficient.”

However, on December 2, 2019—about two months before the US Health and Human Services department declared the coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency on January 31—the DEA had reduced the fentanyl APQ by 31 percent—one of the largest reductions since 2017, the first year of the consecutive annual cuts.

Before finalizing that proposed reduction, the DEA was informed on October 15 in a letter by the American Medical Association and two other professional organizations that they were “extremely concerned” that the proposed 2020 APQs “could exacerbate existing shortages of injectable opioids,” like fentanyl. Additionally, they “remain concerned that reducing overall APQ will result in an insufficient supply of IV opioids to meet the United States’ legitimate needs.” The Mayo Clinic, a highly regarded medical institution in Minnesota, expressed similar concerns.

Healthcare workers and organizations also cautioned against the cuts. “Such dramatic reductions in the production of fentanyl is extremely problematic for American healthcare providers,” wrote nearly 50 medical professionals in seemingly-coordinated comments to the agency’s proposal. “However, it is extremely likely, if not a fact, that allowing this proposal to pass will adversely effect patients and healthcare organizations in the coming year.”

APQs are statutorily required and are not “arbitrarily” set, the DEA spokesperson told Filter. The agency considers factors such as “estimates of the legitimate medical need,” “estimates of retail consumption,” and “manufacturers’ data on actual production, sales, existing inventory, disposal, exports, product development needs, availability of raw materials, potential disruptions to production, and manufacturing losses,” among others.

The DEA’s new APQ increase comes as manufacturers are responding to a wave of requests for injectable fentanyl. Pfizer, the second-largest pharmaceutical company in the world and an injectable fentanyl producer, “has seen an across the board increase in medicines used in treatment of patients with COVID-19, including fentanyl injection which is used as part of protocols for patients on mechanical ventilation,” a company representative told Filter.

Before the coronavirus pandemic hit, Pfizer had already been seeing injectable fentanyl shortages. According to numbers reported by the company on July 1, 2019, two types out of three of such products’ supplies were “depleted.” They estimated that each product’s supply for would respectively “recover” in December 2019 and February 2020.

Pfizer was approved by the DEA on March 31 to produce more fentanyl-related medications. “This increase will enable us to distribute additional product into the market during the remainder of 2020,” said the representative.

Pfizer is not alone in its shortages. Since the initial 2017 cuts, multiple unnamed manufacturers have warned the DEA that the quotas are “potentially insufficient”—like for “the establishment and maintenance of reserve stocks—year after year after year.

Although the DEA recognizes that demand has “substantially increased,” the agency still claims that “the existing 2020 quota level is sufficient to meet current needs,” according to the recent action notice. The increased cap, per a DEA statement, is an effort to act “proactively to ensure that—should the public health emergency become more acute—there is sufficient quota for these important drugs.”

The spokesperson said that the DEA is statutorily required to consider the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) “estimates of the legitimate medical need.” But the FDA lists fentanyl as “currently in shortage,” and has done so since the production cuts began in 2017. The DEA spokesperson referred Filter to the FDA when asked about the discrepancy. When asked to comment on the relationship between the DEA’s APQ cuts and the current and historic fentanyl shortages, an FDA spokesperson simply directed Filter to the agency’s website.

The contradictions between the two agencies’ claims are not necessarily a surprise. The DEA and the FDA have had a documented history of poor communication, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found. “Despite statutory provisions requiring DEA and FDA to coordinate certain efforts to address shortages of drugs containing controlled substances,” stated its 2015 report, “the agencies have not established a sufficiently collaborative relationship.” To the contrary, the DEA spokesperson said that the “DEA maintains a good relationship with” the FDA.

The DEA has pursued the depletion of the legal fentanyl supply in the name of curbing diversion and saving lives. But fentanyl diversion is comparatively “a very small issue overall,” Bryce Pardo, an associate policy researcher at the RAND Corporation and author of multiple reports on fentanyl, told Filter.

Based off the DEA’s estimate for 2018—the numbers cited for its original 2020 APQ decision in December 2019—only 0.008 percent (0.109 kilograms) of fentanyl’s overall APQ (1.35 kilograms) was diverted, the lowest proportion and quantity of diversion of any of the five opioids that are subject to “special scrutiny” by the 2018 SUPPORT Act.

In contrast, diversion for other opioids was comparatively higher: 0.02 percent (1.157 kilograms) of oxymorphone’s APQ (26.600 kilograms); 0.04 percent (24.259 kilograms) of hydrocodone’s (520,220 kilograms); 0.02 percent (1.129 kilograms) of hydromorphone’s (5,140.8 kilograms); and 0.05 percent (57.051 kilograms) of oxycodone’s (104,110 kilograms).

Despite fentanyl’s comparatively low diversion rates, the DEA lowered its APQ because “demand has been reduced, alternative treatment methods for pain are on the rise, practitioners are prescribing less due to CDC guidelines, opioid addiction awareness campaigns have helped Americans become more cautious about taking opioids for routine/acute discomfort, and DEA has put on trainings for registrants and done Take Back events twice a year,” said the spokesperson. “All these actions have been taken to help end the opioid epidemic which has cost the lives of so many Americans.”

For Pardo, the fact that the DEA has now increased manufacturers’ potential supply is promising. “Everyone across the board in federal government is trying to respond to COVID-19 in a way that they can,” he said. “DEA has this lever, which is APQs, so they’re going to go ahead and pull the lever because somebody in DEA realizes this is a massive problem and they’re going to alleviate it in the way that they know how.”

Photograph of nurse anesthetist intubating a patient in 2017 by Shejal Pulivarti via Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

Show Comments