Public opinion is souring on the criminalization of drug use. But what prevents this from translating into practice?

While politicians makes laws and police officers can arrest whoever they find in possession of drugs, it’s prosecutors who turn arrests into criminal charges. Prosecutors have the final say in who to charge with a crime, which charge to use, and what punishment will be sought.

In short, they’re in a position to inflict great harm.

Amy Weirich, district attorney for Shelby County, Tennessee (which includes Memphis), charged women with child abuse for being dependent on drugs while pregnant. She justified this by stating that she uses the “velvet hammer” of drug court to force them into treatment.

In Tucson, Arizona, Pima County Attorney Barbara LaWall sent the ACLU a cease-and-desist letter to try to stop the organization from talking about her support of mandatory minimum prison sentences for drugs.

Commonwealth’s Attorney Raymond Morrogh of Fairfax, Virginia went to Washington, DC to accuse former US Attorney General Eric Holder of trying to reward drug prisoners with “lighter sentences because America can’t balance its budget.”

Filter’s Nationwide Investigation

There are over 2,000 elected local head prosecutors, most commonly known as district attorneys, in the United States. And overall, these powerful individuals do not care what people think about the War on Drugs. They are going to fight it anyway, and hope that the voting public doesn’t notice.

That is the conclusion of an exclusive investigation from Filter, which surveyed the top prosecutors of the nation’s 50 most populous counties. (We included incumbents, outgoing incumbents, incoming DAs and challengers, making 61 individuals in total.) The full results (which have been updated to reflect the results of the November 6 elections*) are presented in map, chart and table forms here.

After collecting public statements and reviewing cases, we emailed each prosecutor a short questionnaire about their positions on four key issues: marijuana legalization, drug-induced homicide prosecutions, mandatory minimum sentences for drugs, and the criminalization of relapse.

Around half of their offices never responded, even after a round of reminders. We telephoned 10 offices, which listed no email address for a media representative on their government websites. One of them—that of Wake County, NC District Attorney Lorrin Freeman—hung up immediately on hearing the word “reporter.”

Many of the prosecutors surveyed have stated publicly that we must treat drug use as a “public health issue,” rather than a criminal justice one. But our findings show that the vast majority nonetheless support or implement practices that drive criminalization, inequality and large-scale human suffering.

Most Prosecutors Still Radically Oppose Marijuana Legalization

When an elderly Vietnam War veteran said at a 2015 Tempe, Arizona town hall that he used marijuana to cope with a medical condition, Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomery declared that he had “no respect” for him and called him the “enemy.”

When San Antonio City Hall was discussing a potential marijuana diversion program, Bexar County District Attorney Nico LaHood (whose re-election bid failed in the Democratic primary in March) “stormed in,” then karate-chopped a table, screaming that he would “never support” legalizing marijuana.

In Minnesota, Hennepin County (Minneapolis) Attorney Michael O. Freeman claimed that today’s marijuana is “bad news bears.” When it was revealed that felony marijuana stings in Minneapolis almost exclusively targeted Black people, Freeman feigned ignorance.

A large number of America’s top prosecutors still fearmonger over marijuana, despite the fact that most Americans (Republicans included) favor legalization.

Overall, 41 of 61 (67 percent) of the prosecutors we surveyed have failed to support or are opposed to legalization or decriminalization. Five (8 percent) support decriminalization, and 12 (20 percent) have instituted or cooperated with a county cite-and-release program, whereby people get a court summons but are not arrested.

Only a single incumbent prosecutor, Cy Vance of Manhattan, publicly supports legalization, as he says, “once and for all”—despite being harshly punitive to poor people of color, including setting prohibitively high bail fees for people arrested on misdemeanor charges. (Hennepin County, Minnesota challenger Mark Haase also supports legalization).

“After I received a felony conviction for possession of marijuana, it led to being involved in more criminal activity out of survival. I was denied housing, jobs, and the opportunity to go to college.”

While decriminalization programs are vastly preferable to no change, police officers can—and do—ignore policy mandates from DAs. In a county where marijuana is technically “decriminalized,” DA offices, too, can effectively ignore that by applying other charges, like disorderly conduct, to people found in possession, as happens in Brooklyn. After Harris County, Texas, DA Kim Ogg launched her office’s decriminalization program, for example, cops outside of Houston ignored it.

Many people who support marijuana legalization do so out of concerns over racial equity. And even when decriminalization is followed faithfully, racial injustice can still run rampant. Dianna Houenou, policy counsel at the ACLU of New Jersey, told Filter that “simply replacing criminal sanctions with civil fines [as happens under decriminalization] is yet another tool that keeps people in poverty,” and can even lead to arrests for nonpayment. It is also “foreseeable that these arrests will continue to disproportionately impact poor people and people of color.”

Decriminalization additionally fails to mitigate a history of racist enforcement, whereas appropriately tailored legalization efforts can mitigate damage through employment opportunities. (That’s not to say legalization efforts thus far have necessarily succeeded.)

Police have also used the illegality of marijuana to justify violence. After Philando Castile, a Black man, was shot and killed by an officer in Ramsey County, Minnesota in 2016, the officer claimed that a marijuana smell from Castile’s car justified it. A jury acquitted him of manslaughter.

Even where small amounts of marijuana are decriminalized, prosecutors can still charge people with felonies for selling or for having certain quantities.

“After I received a felony conviction for possession of marijuana, it led to being involved in more criminal activity out of survival,” Tonja Honsey, a formerly incarcerated community organizer in Minnesota, told Filter. “I was denied housing, jobs, and the opportunity to go to college. The only option I saw was to start to sell drugs to provide for my family.”

The Overdose Crisis Breeds a Vengeful Approach

“Drug-induced homicide” laws allow prosecutors to charge people who provided drugs involved in an overdose death with homicide. Many of these laws were first passed as a response to basketball star Len Bias’s overdose death in 1986. But the charge became a common part of the prosecutor’s repertoire only recently—contemporaneous with courts like the Mississippi Supreme Court and the Virginia Court of Appeals seriously curtailing its potential use.

The uptick in these prosecutions has had no effect on the frequency of overdose deaths. The people on the receiving end are often friends and family members of the deceased, and these prosecutions can deter people from calling 911.

Eighteen (30 percent) of our 61 prosecutors have used the charge for members of public at least once, while six of 61 (10 percent) are explicitly open to doing so in the future. An additional two prosecutors have used the charge specifically for doctors involved in a patient’s fatal overdose.

No prosecutor surveyed has ruled out drug-induced homicide prosecutions completely.

Drug-induced homicide prosecutions are most prevalent in the Midwest and Northeast, where the current overdose crisis is hitting the hardest. In Columbus, Ohio, Franklin County Prosecutor Ron O’Brien has said: “If we can prove it, we are going to charge you with manslaughter.” In New York, Nassau County District Attorney Madeline Singas, who has a self-styled “heroin war room,” pushed for a bill to permit prosecutors there to follow suit.

Some DA offices in these regions may become more judicious in how they charge these cases in future. For example, in Hennepin County, Minnesota, Mike Freeman uses these charges frequently, and has said he makes “no apology.”

Mandatory Minimums for Drugs May Be Fading Out

Getting rid of mandatory minimum sentencing, especially for drug-law violations, has strong bipartisan support. That’s because mandatory minimums impede individualized consideration of fair sentencing based on the facts of the case and defendants’ characteristics. Historically, prosecutors have used mandatory minimums to obtain disproportionately punitive sentences.

In the name of “consistency,” these sentencing provisions take power from judges and siphon it to prosecutors, who already have power over how to charge cases. Prosecutors often use the threat of a high mandatory minimum to coerce defendants to plead guilty to lesser charges, rather than risk fighting a charge with a potentially terrifying sentence attached.

Twenty-two of our 61 prosecutors (36 percent) either explicitly support mandatory minimums for drugs or use them without criticism. Four (7 percent) do use charges with these sentencing provisions, but have also publicly criticized mandatory minimum laws. Two prosecutors—Larry Krasner of Philadelphia and Marian Ryan of Middlesex County, Massachusetts—are opposed to mandatory minimum sentences for drugs.

The rest of our prosecutors work in states where these provisions do not exist, and have not stated positions one way or the other.

Prosecutor Keith Kaneshiro of Honolulu County, Hawaii—who has attracted national attention for running a domestic violence victim jail—justified drug mandatory minimums by stating: “there’s got to be…consequences for criminal conduct.” His statement is typical of supporters of these sanctions.

However, as our survey reflects, several prosecutors have spoken out against these laws. For example, DA Marian Ryan of Middlesex, Massachusetts, claimed while facing a competitive primary in September that her advocacy “played a part in the change in mandatory minimums for a number of drug offenses.” (Ryan won the primary and is uncontested in the November election).

The top prosecutors in Salt Lake City, Utah, San Jose, California, and other large cities also issued a joint statement denouncing Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ demands for increased use of drug mandatory minimums.

Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, told Filter: “We’re encouraged that more local prosecutors are questioning the effectiveness of mandatory minimums, especially in drug cases.” But other prosecutors have lobbied state legislatures for more mandatory sentencing laws. “These are naked power grabs cloaked in the language of public safety,” said Ring.

Prosecutors Swim Against the Science on Addiction

DA Stephen A. Zappala, Jr. of Allegheny County (Pittsburgh), Pennsylvania, continues to prosecute marijuana cases, fights to bring drug mandatory minimums back to his state, and charges fatal overdoses as homicides. But unlike many DAs surveyed, Zappala admits that the criminal justice system field “is not well equipped to handle” drug addiction.

Most prosecutors see drug courts—programs that seek to reduce drug use through mandated treatment and close judicial oversight—as the solution. Fifty-five of our 61 prosecutors (90 percent) support and/or employ drug courts.

Prosecutor Jessica Cooper of Oakland County, Michigan, received criticism for shuttering a drug court in 2009—stating that she needed to save her “severely diminished financial and personnel resources to deal with the surge in violent crime and the surge in technically complex cases”—but even her county currently has a drug court.

In San Diego County, DA Summer Stephan’s office told Filter that “relapse is often a part of the process and does not result in being dismissed” from her office’s drug use program. In general, however, as drug users relapse, they face a range of sanctions, including imprisonment.

DA Bob McCulloch of St. Louis County, Missouri once said of drug court: “It’s not an easy program to get through, but it has been effective in many instances.” Drug court is sometimes so punitive that, as DA Mike Hestrin of Riverside County, California lamented when state voters defelonized drug possession with Proposition 47: “If you say to them, spend two weeks in jail or be in a year-long drug treatment program, they take the jail.”

“What other health conditions are subject to arrest by virtue of the person having them becoming symptomatic for them?”

Jeff Deeney, former case manager with Philadelphia’s Treatment Court Program, agrees with these assessments. Deeney told Filter that drug courts “use consequences in order to stop addiction when the definition of addiction is continued use despite consequences. Additionally, with sufficient outreach and engagement, users can be brought into the treatment system without arrest or the threat of punishment.”

Diversion programs are employed by four of our 61 prosecutors (7 percent). The best known of them, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program, pioneered in part by Prosecuting Attorney Dan Satterberg of King County (Seattle), Washington, goes a step further than most drug courts.

It is a pre-booking program, which means that people who qualify are diverted before they are arrested or charged with a crime. But it struggles with its claimed public health goal. Eligibility requirements, like a lack of serious criminal history and a three-gram limit on drugs possessed, contravene the science of addiction. LEAD can also ensnare more people in the criminal justice system if officers are fishing for people who fit an “addict” profile.

Deeney agrees that LEAD and similar diversion programs are a step in the right direction, but objects to the idea that these programs are treatment options that do not punish relapse. “What other health conditions are subject to arrest by virtue of the person having them becoming symptomatic for them?” he asked.

Can Elected Prosecutors Move Drug Policy Forward?

Some major urban county district attorneys have acknowledged that the War on Drugs is a failure. A number have made changes toward curtailing the practices associated with it, but old habits are hard to kick.

Most DAs in our survey who have instituted reforms are prosecutors elected in the last few years. Former civil rights attorney Larry Krasner, elected as Philadelphia DA last November, has been working to end mass incarceration from the inside.

The traditional way of discussing the job is that the “law is the law”—or, as Palm Beach County State Attorney Dave Aronberg’s office wrote in declining our questionnaire, DAs are “constitutionally and ethically required to enforce the laws” as written. Yet anyone who has compared counties by criminal justice outcomes, even when adjusting for crime rates, knows that the reality of enforcement is much more complex—in a world of limited resources, prosecutorial discretion is key.

Interest in DA elections exploded after the Black Lives Matter movement brought national attention to holding law enforcement accountable. Now, the ACLU is spreading awareness through its Smart Justice campaign, while Color of Change PAC, Real Justice PAC, the former Vermont Governor Howard Dean-founded Democracy for America, and philanthropist George Soros offer organizing and financial support for reform. Famous R&B singer John Legend, contemporary street artist Shepard Fairey, and other celebrities have also weighed in on district attorney races.

After Wesley Bell, a Black city councilman in Ferguson, Missouri, defeated Bob McCulloch in the 2018 St. Louis County district attorney race, Jennifer Soble from the Justice Collaborative Engagement Project said: “Our jail population is out of control. Locally elected county prosecutors have the greatest capacity to change that instantly, more than any other actor in the system.”

Two other prosecutors in the 50 most populous counties—Michael Ramos of San Bernardino County, California and Nico LaHood of Bexar County, Texas—also lost their re-election bids this year to candidates seeking to reform their local justice system.

On September 4, 2018, Rachael Rollins won the Democratic primary for District Attorney in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, which includes Boston (but isn’t one of the 50 most populous counties surveyed). If successful in November, she will become the one top prosecutor in America who has promised to decriminalize drug possession.

Prosecutors should be able to usher in important changes to the criminal “justice” system. If they refuse to, as still seems likely in most cases, they will remain some of the most significant roadblocks to a more humane drug-policy future.

*The map, charts and table referenced in this article have been updated to reflect the results of the November 6 elections. Post-election, the results include:

- Only one out of 50 (2 percent) of incoming and current district attorneys in the US’s 50 most populous counties support marijuana legalization.

- Of the district attorneys who provided answers to us or for whom we found data about drug-induced homicide prosecution, 96 percent have charged or are open to charging someone for drug-induced homicide.

- Nineteen prosecutors out of 50 (38 percent) either explicitly support mandatory minimums for drugs or use them without criticism. Two prosecutors—Larry Krasner of Philadelphia and Marian Ryan of Middlesex County, Massachusetts—are opposed to mandatory minimum sentences for drugs.

- Almost all—92 percent—support and/or employ drug court.

Rory Fleming has worked on district attorney campaigns in cities including Charlotte, San Diego, Boston, and Birmingham, Alabama.

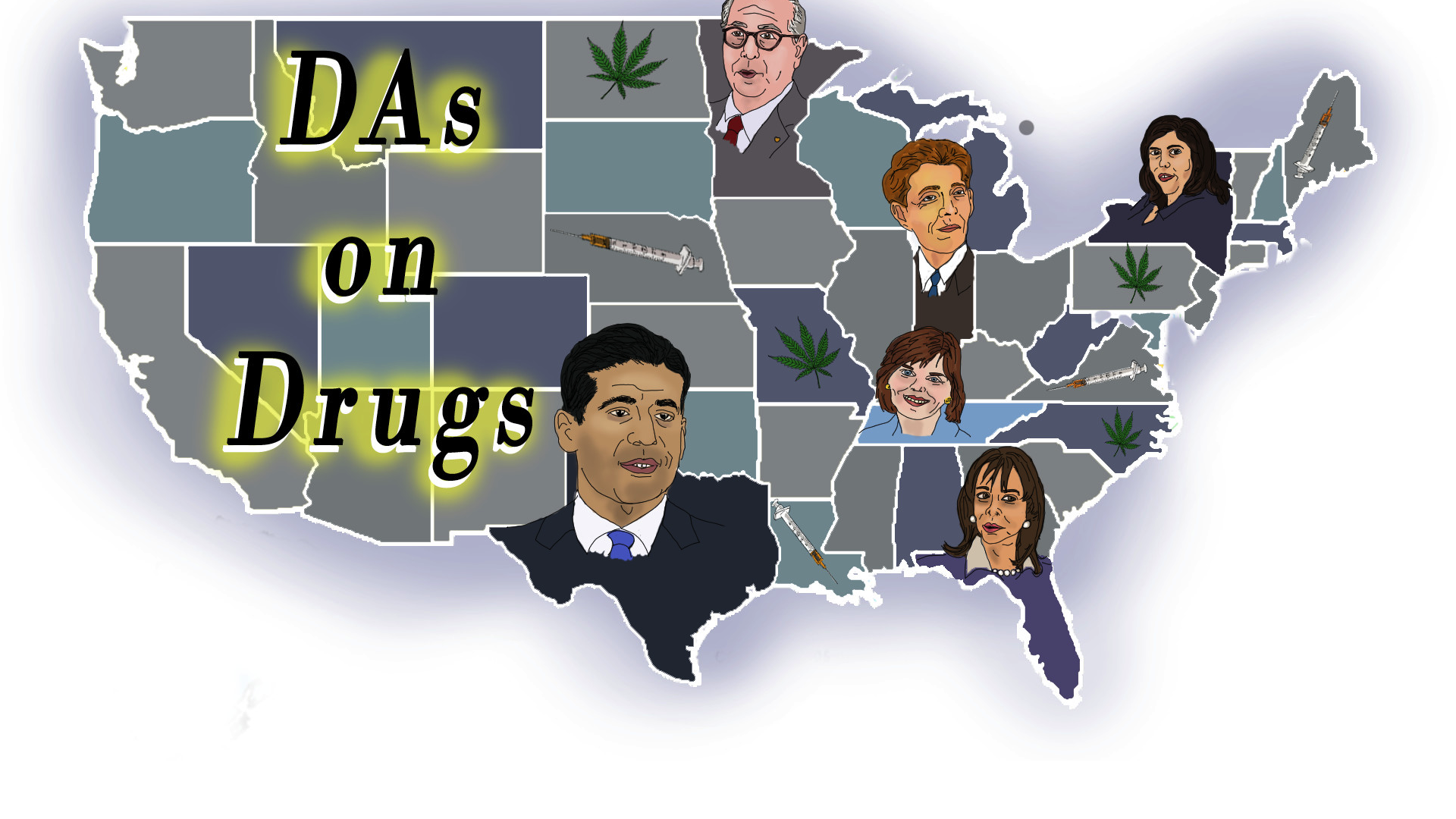

The artwork is by Sarah Etten. It depicts: Mike Freeman (Hennepin, MN); Nico LaHood (Bexar, TX); Madeline Singas (Nassau, NY); Amy Weirich (Shelby, TN); Katherine Fernandez Rundle (Miami-Dade, FL); and Ron O’Brien (Franklin, Ohio).