Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has shut the International Criminal Court (ICC) out of the country as it attempts to investigate former President Rodrigo Duterte’s War on Drugs. “That ends all our involvement with the ICC …. At this point, we essentially are disengaging from any contact, any communication,” Marcos said, according to Reuters. His actions jeopardize, and perhaps end completely, an international inquiry into tens of thousands of killings.

Since Dutere came became president in 2016, soldiers, police and armed vigilantes have waged a bloody, nationwide campaign against alleged drug users and sellers in the Philippines, as documented by Human Rights Watch. Officers are required to keep lists of drug suspects, and rewarded for their efforts—official incentives that perpetuate the violence. People are targeted on mere suspicions, and often on the basis of personal or political animosity. Amnesty International has also found that police plant evidence, falsify reports and steal from victims’ homes. It’s impossible to know the true toll of this murderous campaign, but the ICC estimates between 12,000 and 30,000 civilian deaths.

Marcos’ action is a major strike against accountability for Duterte. It also betrays the reality that even with a new president, little has changed on the ground.

Early in his 2016-2022 tenure, Duterte’s actions were already drawing worldwide condemnation. A lawyer in the Philippines filed a complaint that led the ICC to consider an investigation into the killings. After taunting the ICC and claiming he would happily “rot in jail,” Duterte then announced in March 2018 that the Philippines would withdraw from the Rome Statute, the founding international treaty that created the ICC. The withdrawal became effective in 2019.

In September 2021, the ICC opened an investigation into drug war killings under Duterte. It focuses on two periods—November 2011 to June 2016, when Duterte waged a similar campaign as mayor of Davao City, and then up to March 2019, after Duterte became president but before the withdrawal from the ICC treaty. ICC rules allow it to investigate any crimes that happened while the country was still a treaty member.

But soon afterwards, in November 2021, the ICC’s chief prosecutor granted the Philippines government’s request and temporarily suspended the investigation. According to the ICC, the Philippines was conducting its own investigation and the court would decide at a later point how to proceed.

Then in January 2023, the ICC allowed the prosecutor to reopen the investigation. It stated that the Philippines government was not conducting a serious investigation of its own. President Marcos, who had come to power in May 2022, appealed the decision in February 2023, asking the ICC to suspend the investigation again. That request wasn’t granted. So on March 28, Marcos announced he was cutting off the ICC—damning any further efforts to investigate Duterte.

“We cannot cooperate with the ICC,” he said, “considering the very serious questions about their jurisdiction and about what we consider to be interference and practically attacks on the sovereignty of the republic.”

“We still hear from local activists that extrajudicial killings are taking place.”

Marcos’ action is a major strike against accountability for Duterte. It also betrays the reality that even with a new president, little has changed on the ground.

“As of 2021, we still hear from local activists that extrajudicial killings are taking place,” Ajeng Larasati, human rights lead for Harm Reduction International, told Filter. “The Philippines in the past few months is still debating reinstating the death penalty for drug offenses as well. It doesn’t seem Marcos has taken any steps to make its drug policy better and more respectful of human rights.”

Human Rights Watch has also stated that drug war killings are still happening daily, and activists and journalists who speak out are scared into silence or even killed in retaliation.

According to Human Rights Watch, if the investigation produces evidence of crimes committed during the court’s jurisdiction, ICC judges must approve an arrest warrant or summons to appear on specific charges. This could take anywhere from two months to six years—and it’s impossible to predict how long the investigation itself would take. If judges are satisfied there is sufficient evidence to support an indictment, they will set a trial. Individuals who could be indicted include those who committed a crime, who gave an order or were in a chain of command and didn’t report wrongdoing.

The ICC has largely struggled to complete criminal cases even with individuals it has indicted, because it has to rely on member state governments to make arrests. To date, 14 people worldwide with arrest warrants have never been apprehended. But 30 people have been summoned before the court or faced trial—including individuals involved in the Darfur genocide, the Rwanda genocide, conflict in the Central African Republic, and the Mali War.

With President Marcos taking a hardline stance against the ICC, the prospect of drug war victims seeking justice through that court seems slim. But first-hand accounts of Philippines drug war abuses will continue to be documented by human rights organizations.

“Just the fact the ICC is reopening the case is already a good step,” Lasarati said. “Although it may not end up in an investigation, it still gave the Philippines government a sense that the international community is watching.”

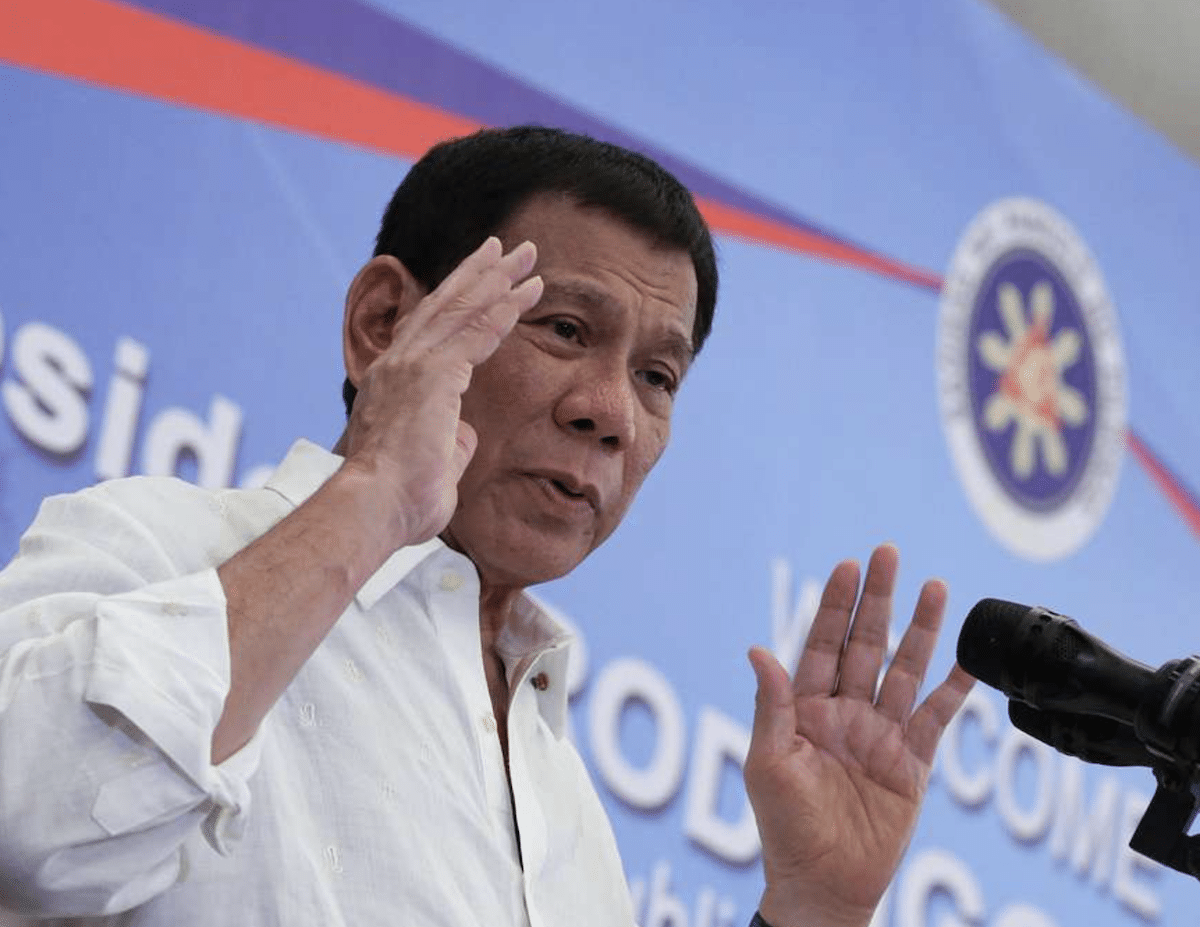

Photograph of Duterte in 2016 via Picryl/Public Domain