For those of us who are suffering, how do we find joy and experience pleasure? How do we create a world in which less suffering is possible? What does it look like to build community in the face of such suffering, and how can we create communities that are safe for each and every person?

These are the questions that Sarah Ziegenhorn, the 30-year-old executive director of the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition and a medical student at the University of Iowa, had in mind when she and her team organized the fourth annual Iowa Harm Reduction Summit. It took place October 3-5 in Iowa City in the name of Andy Beeler, who died in his home from an accidental heroin overdose in March. Beeler was a program coordinator at the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition, beloved by the participants to whom he dedicated his life.

Far from an abstraction, the questions raised by Ziegenhorn were present throughout the weekend. Deaths involving synthetic opioids like illicit fentanyl tripled from 2011 to 2017, while those involving heroin quadrupled from 2012 to 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2017, stimulants like methamphetamine contributed to 28 percent of the 342 overdose deaths in Iowa, according to Iowa’s Department of Public Health. A mix of heroin, illicit fentanyl and meth is contributing to an upswing in morbidity and mortality across the plains of Iowa and the Midwest at large.

A much-anticipated Saturday night presidential candidate forum was postponed after Senator Bernie Sanders—who was slated to wax on health care, drug policy and criminal justice reform—had a heart attack. “Due to Senator Sanders’ illness, we are postponing tomorrow evening’s kick-off candidate forum,” Ziegenhorn wrote in an email to panelists and speakers from out of town. “Because many of you arranged travel plans to Iowa around this event, we are throwing a party instead.”

Many Iowans directly impacted by chaotic drug use and inhumane policies drove hours.

Grim statistics and the big heart of America’s leading socialist giving out did not diminish the spirited, vulnerable tone of the weekend. Hundreds of people showed up with all the urgency that Ziegenhorn’s questions express.

At many harm reduction conferences, people tend to fly in from the usual hubs: New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle and the Bay Area. While these harm reduction hotspots were well represented in Iowa, sharing decades of wisdom and up-and-coming programs, the substance of the Summit was distinctly Midwestern. Many Iowans directly impacted by chaotic drug use and inhumane policies drove hours to hear about how to expand services that save lives, and learn about innovative strategies to mitigate harms to people who use drugs and sex workers.

Drug User Organizing in a Red State

Topics ranged from “Eliminating Hepatitis C in Iowa: Building Financial Sustainability for Payers and Providers” to “Drug User Organizing.” In the latter meeting, led by activists Jess Tilley and Louise Vincent, nearly 40 people who identified themselves as drug users sat in a circle and engaged with the difficult task of how to organize in their communities and fight to be treated with dignity by medical, legal and other institutions.

Christopher Abert, former executive director of the Indiana Recovery Alliance and founder of Southwest Recovery Alliance, told Filter how inspiring this had felt. “So many people identified as using drugs,” he said. “I’ve never seen anything like that before.” Indeed, they were mostly strangers to one another, but Abert felt a unique vulnerability and openness.

Tilley, who smiles with her eyes and frequently calls herself “jaded,” shared with the group how safe she felt there, and then got down to the business of people who use drugs engaging in direct action against punitive drug laws. Tilley and Vincent used their Reframe the Blame campaign, which targets cruel and misplaced drug-induced homicide laws, as an example of how people can make their voices heard.

In the rural Hawkeye State, is harm reduction really being embraced?

Having flown in from Chicago, where harm reduction groups like the Chicago Recovery Alliance have a 25-year history, I had a question on my mind beyond those Ziegenhorn raised.

In the rural Hawkeye State—which President Trump carried by the largest margin of any Republican candidate since Ronald Reagan in 1980, and where conservatives maintain a trifecta of control over the House, Senate and Governor’s office—are harm reduction services, like naloxone and syringe distribution, fentanyl test strips and support for sex workers, really being embraced?

The answer, I learned, is an unsatisfying yes and no. But groups like the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition are moving the needle. Part of this involves building bridges with critical institutions at the University and the state’s criminal-legal system. Except for the police chief.

Me: Hello, I would like to invite you to attend a conference on the overdose crisis & drug policy.

100 speakers from around the world: you bet.

Bernie Sanders: I’ll be there.

1000 guests: deal.

Local police chief: you’re a criminal, no thanks.

— Sarah Ziegenhorn (@sarah_ziggy) September 30, 2019

A Troubled Relationship With Religion

An exchange during one of the weekend’s most moving workshops illustrated the moral and political complexity of providing harm reduction services in deep-red political terrain and within conservative institutions.

Early Saturday morning, Blyth Barnow, of Faith in Public Life, had delivered what was by all accounts a fiery sermon on bridging the gap between harm reduction and the Christian church.

“As a community organizer, I knew that better understanding the language and values of Christianity could be a powerful tool when attempting to make change somewhere like Ohio,” Barnow said with the force of a preacher. “But perhaps most importantly, I wanted to learn how to bury my friends with dignity, because nobody else ever had.”

The pastor at the funeral condemned him to Hell for his sins.

When Barnow’s ex-boyfriend died from an overdose 15 years ago, she was livid in the aftermath.

“I lost one of my first loves to an accidental overdose on heroin and crack,” she said. “He came from a family of evangelical Christians, and at his funeral all his friends who had been caring for him sat in the back of the church while his family, who I trust loved him in some way, but who also kicked him out and called him an abomination, got to sit up front.”

The pastor at the funeral condemned him to Hell for his sins.

“In theory it would be easy to say ‘fuck the church’ and walk away,” said Barnow. “It is harder to admit that that day, the pastor reaffirmed what many of us already felt—that we were worthless, we were broken, we were dirty, and that we ought to be ashamed of ourselves. I sat in a row of about 10 of my friends that day, and almost all of them are dead or locked up now.”

She continued, “In our society, clergy are granted authority and power. His words had the power to turn our self-criticism into a truth. It created so much harm. And I truly believe that hearing that message from a pulpit was part of what cost my friends their life and their freedom. When left unchecked, toxic theology kills people. Which is why we need to get and stay in the mix.”

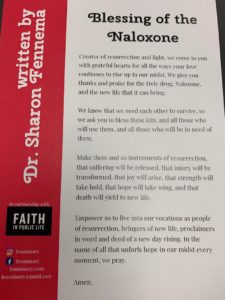

Ever since she graduated from seminary, Barnow and others, like Rev. M Barclay and Erica Poellot, director of faith and community partnerships at the Harm Reduction Coalition, have been pushing religious communities to embrace harm reduction. Connecting biblical concepts like resurrection to lifesaving drugs like naloxone, the overdose antidote, Barnow has organized church services called “Naloxone Saves,” at which naloxone kits are blessed on the altar.

“It was harm reduction that taught me that resurrection is possible,” Barnow told the room. “Harm reductionists are some of the most powerful ministers I know, whether they want to claim that title or not.”

After Rev. M, Barnow and Poellot took turns speaking, Ziegenhorn shared how local church communities in Iowa shut the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition out, refusing to give them space to store syringes and naloxone. Ziegenhorn said her team sent emails to local churches about the faith and harm reduction workshop, and in terms of those local churches, “nobody fucking showed up!”

Barnow, Poellot and Rev. Meg Wagner, of the Episcopal Diocese of Iowa, shared Ziegenhorn’s frustration and told her to not give up. It will take time and patience, they said, to engage with traditionally conservative institutions about harm reduction concepts.

They’re simply fighting so that they and their loved ones, year-by-year, can suffer a little less.

But with powerful synthetic fentanyl analogues taking over the heroin market, spreading across the Midwest from the East Coast, time is an unaffordable luxury.

The Iowa Harm Reduction Summit was instituted four years ago as a series of talks and panels to teach medical students how to better care for people who use drugs in their community. Today, the coalition constitutes Iowa’s largest free naloxone distribution program and provider of opioid overdose prevention education, and the Summit attracted hundreds of people.

Beeler, who was 30 when he died, was Ziegenhorn’s partner. A generation of people from all kinds of backgrounds and professions has grown up in a world of unfathomable grief. Yet even if harm reduction concepts are not being embraced by conservative legislators in red states (nor even by liberal politicians in big cities), this generation is fighting to create a world where people don’t have to grow up losing so many loved ones.

Hundreds of attendees at this year’s Summit were among those who have suffered. They’re simply fighting so that they and their loved ones, year-by-year, can suffer a little less.

All photographs by Zachary Siegel.