You could get crack before you got something to eat,” said Uneeda Nichols, 46, looking back on her adolescent years during the crack cocaine era of the 1980s. Over the course of nearly 15 years of crack use, addiction and law enforcement uprooted her life and landed her two jail sentences before the age of 30. Today, Nichols runs two businesses in Washington, DC.

“When we learned how to cook it up and add extra stuff in it to make it crack, all hell broke loose,” said Nichols, who currently lives in Raleigh, North Carolina. “People started dying, killing and doing things they never thought they’d do for that drug.”

Nichols first used cocaine at age 13, then her cousin introduced her to crack when she was 16. That cousin, to this day, is still addicted to drugs. Even Nichols’ aunt, a 20-year veteran employee of the US Labor Department, lost her job after she started using crack.

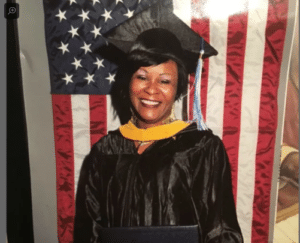

Uneeda Nichols (Credit: Uneeda Nichols)

The First Step Act

People in federal prison may soon benefit from the First Step Act of 2018, signed into law by President Donald Trump on December 22, 2018. Among many changes, the new law makes the crack cocaine sentencing reforms of the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act retroactive.

The Fair Sentencing Act reduced a statutory disparity between powder and crack cocaine sentencing that resulted in much longer sentences for those convicted of crack-related crimes. It had previously stood at a 100:1 ratio—even though crack is just powder cocaine cooked with baking soda and water, allowing it to be smoked for a quicker high than snorting powder cocaine (though if powder is dissolved in water and injected, the high is just as rapid as crack). This racist sentencing disparity was reduced to a ratio of 18:1 in 2010.

Making this reduction retroactive now means that about 2,600 people currently incarcerated in the federal system are eligible for early release, according to the Marshall Project.

People sentenced for crack cocaine offenses have long borne the greatest burden in the federal prison system.

The First Step Act should therefore make a small reduction in a federal prison population of over 181,000. This population, however, is less than 9 percent of the total US jail and prison population of about 2.1 million. To break it down further, nearly half (47 percent) of federal prisoners are incarcerated for a drug-law violation, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. Over 99 percent of those offenses are drug trafficking-related, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics.

People sentenced for crack cocaine offenses have long borne the greatest burden in the federal prison system. They serve the longest average sentences, at over 11 years. Those convicted of crack and powder cocaine offenses also comprise the largest group in the system for drug-related reasons, at over 54 percent of all federal prisoners sentenced for drugs.

A Question of Survival

“It was a question in those days of how do you survive and cope,” says LaTorie Wallace, a DC resident who lived through the crack era. “When you have something that makes money, there’s only two ways to look at it. You’re either gonna consume it or make money off of it.”

Or, you run away. Wallace’s parents resolved to move out of the District to the “safety” of Maryland when she was still a toddler. “They thought if they moved from DC that some of their children would no longer be attracted to the same people and things, but they didn’t move far enough,” she said. Her family of 19 children relocated just across the street from the city line.

The casualties of the crack wars followed them. “When I was old enough to talk to neighbors,” Wallace said, “I realized there were other people coming from DC who were displaced children put in foster homes. Many of their parents were either in jail, or strung out.”

“Several Steps Back”

Though hailed as the first major criminal justice reform in almost a decade and embraced by a bipartisan coalition, including Kim Kardashian, Jared Kushner and the Koch Brothers, the First Step Act is controversial among criminal justice reform advocates for reasons that include its failure to go far enough and its embrace of digital monitoring systems ripe for abuse. (Of course, the reforms it does provide are also controversial among “law and order” hardliners like Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton.)

“This is a tiny step forward, and several back,” said Adam Vine of CageFree Cannabis. Vine criticized the bill’s implementation of risk assessment algorithms to determine which prisoners can be eligible for early release through “good time” and “earned time” credits. These are credits prisoners earn through “good behavior” or by participating in education and rehabilitative programming that reduce time from their total sentence.

“This puts an unnecessary burden on low-income people.”

Risk assessment algorithms provided for in the First Step Act are used to predict a person’s likelihood of committing another crime. They factor in many different data, including prior criminal histories, age and gender. Vine says these systems are notoriously inaccurate and have been shown to discriminate against Black and Latino prisoners. One such program, the subject of a Wisconsin Supreme Court case in 2016, was found to be no more accurate than asking random people in a survey to make predictions.

Vine explained some of the other trade-offs made in the legislation. “Inmates are released early to home confinement with an electronic surveillance bracelet, but the catch is prisons force them to pay for the technology out of pocket. Of course this puts an unnecessary burden on low-income people who can’t afford to do so.”

What Real Reform Would Look Like

Where the First Step Act may fail most is in its inability to reduce any of the broader social and economic inequalities that apply to communities devastated by mass incarceration. Uneeda Nichols explained how the already-impoverished neighborhood where she lived in DC was especially vulnerable to crack. Addiction is, of course, more prevalent and more damaging in poorer, less stable communities.

Nichols first encountered crack in the foster home where she lived. Her parents were unaware that she was using in their overcrowded two-bedroom apartment in southwest DC’s housing projects.

The crack trade offered some the opportunity to make money where none previously existed, but for Nichols, who sold crack and other drugs, this came with a high price tag. Her addiction worsened rapidly. “I didn’t lose anything because I had nothing to lose,” she said. Nichols also engaged in sex work, during which she was raped, and survived however she could. All around her, she says, she saw people breaking into and robbing others’ houses.

“It was the best high I ever had,” Nichols said of crack. “I could escape from everything. But the comedown and the depression is so hard because you got to live with what you did while you were high.”

Nichols sold to an undercover cop, and her house was raided. She was sentenced on several crack and gun-related charges, and at age 22 she received a five-year sentence in a DC correctional facility. After being released in 1997, she was sent back to jail again in 1998 for a one-year sentence. She hasn’t used crack or been back to jail in 20 years, but the systemic failures that harmed her remain.

“We have our own role models that made it out of these hardships.”

“We need more community, not more policy change,” said Nichols, who contributes to her community through the two businesses she runs: a catering company, D.C.’s Sweet Sensations, and a cannabis education program, Gurlz Grow Dank. “We need to let these communities take care of themselves, because they know what’s going on inside. And we have our own role models that made it out of these hardships.”

“A lot of the reason why we used those drugs was because we were ignorant, but we also have a lot of psychological problems that we don’t want to address,” she continued. “People can’t heal unless they work on those things.”

Real reform, Nichols said, means investing in education and training to help community members secure jobs. It means improving access to healthcare and everything else that makes a community work for its people.

“Now when you let all these people out of jail that have been there for 20 years, what are they going to do?” Nichols asked. “Forget technology and social media, these people don’t even know how to put their money on a subway card. But you want them to hop out and be citizens?”

An Old Racist Pattern

LaTorie Wallace, meanwhile, moved back to the District at age 19, and today dedicates her life to restorative justice and social equity, operating the local cannabis educational group We BAKED. In 2018, as a birthday gift to herself as she turned 37, she co-founded the Equity First Alliance to host the first-ever National Expungement Week, which Filter reported on in October 2018. This series of expungement clinics and other educational and social services was offered in cities all around the US.

Wallace’s home city, sadly, does not offer expungement at the moment, only record sealing. And in any case, these are all only small steps towards relieving the burden Wallace feels from having family members still incarcerated to this day. “I really need some people to come home,” she said. “I think 36 years is long enough now.”

“There’s always something behind it.”

Reflecting once more on the First Step Act, Wallace shared the hesitation she feels, as a black woman in America, to celebrate along with other advocates for criminal justice reform.

“There’s always something behind it,” she said. “If we don’t really understand the bill, if we don’t go back to ‘superpredators’, and Reaganomics … We have to look beyond and see the patterns.”

“We have to take it back to 1787,” she continued. “That’s how far back I have to go sometimes, for myself, for my children, and my support group. It’s my job to look at what justice can look like. Anything that’s a part of the government and the plan, we have to look at how it really affects us as people of color. Especially when we’re only counted as ‘three-fifths of a person.’”

Show Comments