March 2020. The stakes were enormous and the urgency acute: 1,000 of our patients were about to be pushed into opioid withdrawal for lack of medication. How many of those enduring miserable days of sweaty, vomiting, panicky withdrawal would fend that off with whatever passed for heroin that day? How many would risk death, and in some cases face shame and loss of function that they had previously overcome?

What chaos would follow the potential losses of societal contributions from these parents, teachers, construction workers, EMTs, grocery store employees, home health workers, farmers and human beings, who would need once again to devote time, energy and money to obtaining illicit drugs? How soon would we see unnecessary spikes in overdose, hepatitis C, heart valve infections and HIV when intravenous drug use suddenly became a daily need again for so many?

But soon after COVID-19 hit our state, just in time for us to keep our patients safe in lockdown, government and private insurance organizations expanded coverage for telehealth. In a short space of time, increased payment to clinics for telehealth services and enhanced flexibility in the rules for connecting virtually with patients have dramatically transformed our practice.

Now we understand that we must fight to keep these changes.

Our health equity medical organization, REACH, in Ithaca, New York, has seen an unexpected and remarkable increase in our ability to help the under-served populations we have historically struggled to keep engaged and healthy. Now we understand that we must fight to keep these changes—not allowing them to expire when President Trump declares an end to the current National Emergency.

COVID-19 Demanded Telehealth, Not Barriers

Our young, nonprofit medical practice serves people from, at last count, 26 counties. We provide them with buprenorphine, the gold-standard, lifesaving daily medication for opioid use disorder (OUD).

REACH Medical is a low-threshold, harm reduction medical practice, additionally offering integrated primary care, testing and treatment for HIV and hepatitis C, and robust behavioral health, care management, and outreach services.

We serve over 1,000 people with OUD in rural and under-served swaths of the Central, Western and Southern Tier areas of New York State. Over 80 percent of our patients are enrolled in Medicaid, 30 percent have no or insecure housing, and many regularly travel hours for their care because help closer to home does not exist.

The pandemic of a century was only the next wrench tossed into our operations.

The March COVID-19 public health emergency declaration put a rapid moratorium on in-person visits. We had no existing infrastructure for telehealth, and we weren’t alone. US medical practices have been devastated by the pandemic, seeing a “55% decrease in revenue and 60% decrease in consumer volume because of COVID-19.” In human terms, this means that six out of 10 times a person would otherwise consult a medical provider, they are now staying home. Many healthcare centers cannot afford to pay employees or keep essential items, like hand sanitizer, in stock.

With our country’s population unable to seek the medical help they need, we began to see one of many secondary crises emerging from the pandemic.

As of March, managed Medicaid and most other insurers paid only a pittance to healthcare providers for telehealth services. With 80 percent of our patients relying on Medicaid—a government program often outsourced to private, profit-driven companies—we would not have survived financially. Providing telehealth services only, we could not have paid our staff. That’s why we faced the overnight removal of a safe alternative to an unpredictable and deadly drug supply for 1,000 people in Upstate New York.

As an organization committed to health equity, we have spent the two years since we opened in 2018 upending and circumventing seemingly arbitrary restrictions on healthcare delivery.

These include extra and expensive training to prescribe buprenorphine; limits on the number of patients to whom we can prescribe it (not required for full opioids like oxycodone); the inability to prescribe while patients are incarcerated, setting them up for high risk of losing tolerance and overdosing upon release; and court mandates that patients participate in non-evidence-based treatment programs with mandatory counseling.

The pandemic of a century was only the next wrench tossed into our operations.

How We Got to Work

We tightened our financial belt for a few weeks, briefly furloughing our part-time, contracted medical providers (all fully employed elsewhere) and re-imagining the job descriptions of our staff to maintain our commitment to being a living-wage employer.

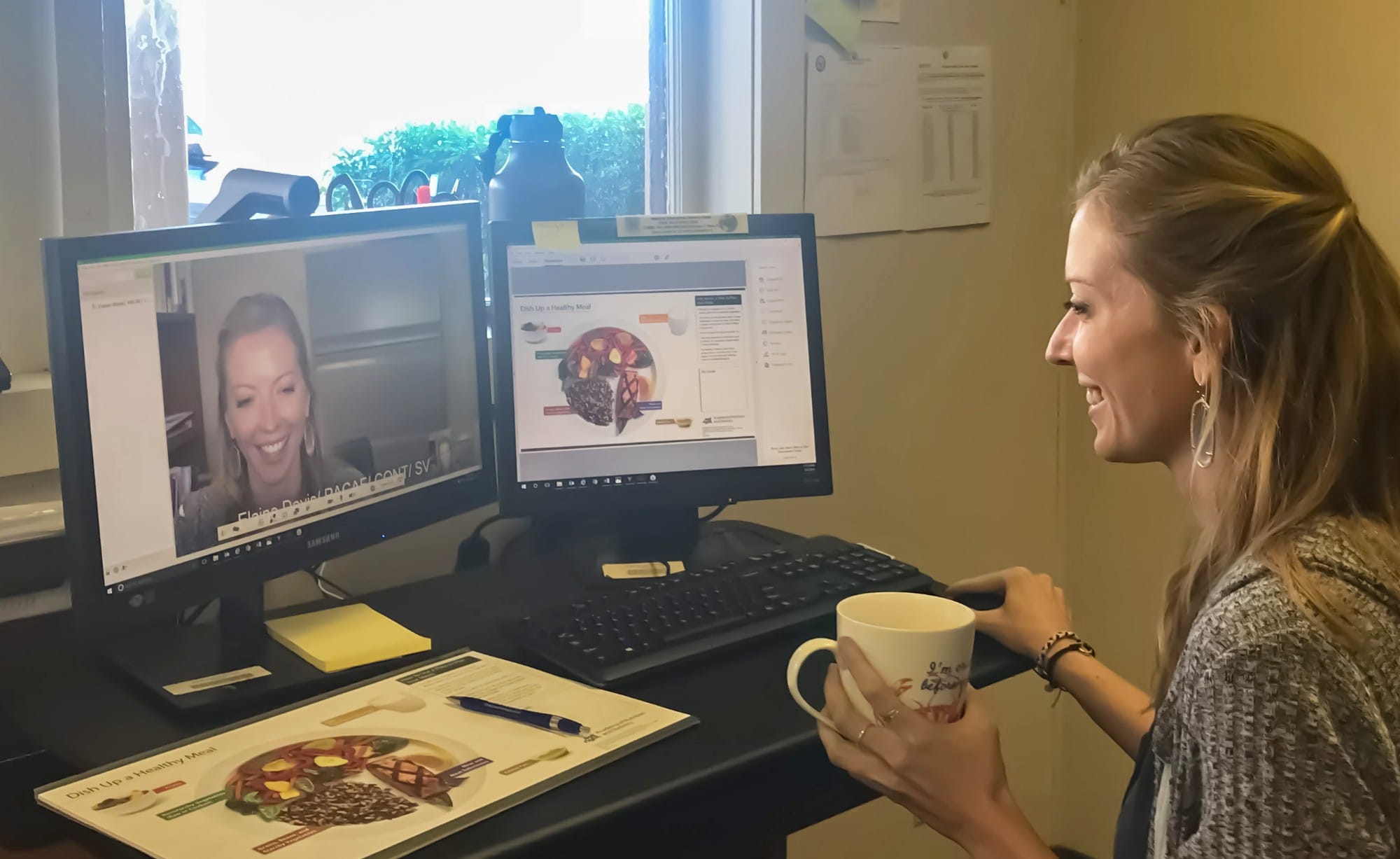

We researched telehealth platforms that didn’t require patients to pay for, or even download, apps. We adapted our electronic medical records with new telehealth templates and kept abreast of changes in billing policy. We retrained our front staff to act as “traffic controllers,” directing our online clinical days.

We expanded our outreach program by sending a community health worker to our local homeless encampment, known as “the Jungle,” to connect people without functional smartphones with on-the-spot telehealth visits, utilizing the worker’s phone. We also opened our virtual doors to patients around the state whose practices were unable to support them through the pandemic.

We kept our collective eye out for expected news of overdose deaths and a growing list of patients “lost to treatment.” We braced ourselves to stave off economic ruin until REACH could be reestablished some time in a distant, different future.

But it turned out, April 2020 was perhaps our best month ever. Part of the evidence for this was the overwhelming positive feedback from the many additional people we reached—adding 53 new OUD medication patients that month.

“I am so grateful for all of you,” said one young woman who was engaged through our in-person telehealth outreach. “I don’t know where I would be without you; you are all so positive. I just appreciate being treated like a human being.” As she spoke, tearing up, she was sitting in the Department of Social Services, trying to get a decent place to live.

“You’re helping me with my fucking medical PTSD.”

Structurally, a flurry of do-or-die decisions came down from federal and state government insurers: Public payment for telehealth was increased from negligible to on par with in-person visits; new patients could now be started on buprenorphine by video or telephone; telehealth visits no longer required the patient to be physically in a medical office. Central to our survival, local managed Medicaid companies opted to honor these guidelines.

Against myriad systemic disadvantages—spotty rural broadband, limited access to electricity or the funds needed to charge and add minutes to phones, part-time jobs with no allowed leave for medical appointments, chronic food insecurity, childhood abuse, domestic violence and violent trauma—our patients showed themselves to be unbelievably resourceful. They save phone minutes for visits, sanitize and share camera phones, walk half an hour to public Wi-Fi at their appointment times.

They are making it happen, even if they give us credit. “As much as I’ve been discriminated against in the past—and I’ve been treated so badly—when I tried to be honest with my doctors in the past, it wasn’t actually a good idea, it turned out,” said one father of four, employed for the first time in five years. “Now I keep having to remind myself, ‘REACH isn’t like that’ and I really can tell you guys how I’m doing and what I need. You’re helping me with my fucking medical PTSD.”

21st-Century Home Visits

In the two months since COVID forced this transformation on our practice, I’ve met three newborn babies whose parents stay healthy with OUD medication.

“This is a REACH baby,” wept one dear patient. “She’s your miracle so please tell everyone on staff what they made possible, that we did it!” I had been able to visit with her virtually in her quiet room on labor and delivery and not only refill her Suboxone but discuss and treat symptoms of postpartum anxiety before the pair were discharged.

We’ve realized how much we’d been missing from the stories we thought we knew.

The insights telehealth has given into the daily lives of our patients have been incredible. We have been taken on virtual walking tours of dairy farms, shared work breaks with essential workers, ridden empty buses through distant Upstate towns, been shown awful tent living conditions and provided sleeping bags in response.

We’ve realized how much we’d been missing from the stories we thought we knew, and this has enabled us to provide more informed care.

Our patients, too, are fully aware of the benefits telehealth has brought—lowering barriers to care and above all, continuing their access to the medication they need.

“If I lost my medication and lost you as my physician, I would probably die and am serious about that,” wrote one.

“I would have already been stealing to buy heroin. I hate to say it, but it’s true,” said another.

The inherent intimacy of rural addiction medicine in the context of people’s homes and lives pulled us from our standard practices and promoted the honesty and trust that is so critical to doctor-patient relationships. As in obstetrics and palliative care, these relationships skip the niceties and demand real connection. We cry daily, swear regularly, ask and answer embarrassing questions, and swell with pride at the teamwork that binds our staff to this service. More than anything, we bring our full selves to work.

This Won’t Fit Back in the Bottle

The rule changes which have allowed REACH to thrive during this emergency transition to telehealth will expire when President Trump declares an end to the National Emergency. But we, and our patients, are unwilling to go back to the old restrictions which insurance agencies were forced to remove.

These are massively overdue advancements which promote health equity for rural and underserved communities. Our patients’ health should not be dependent on decisions driven neither by commitment to evidence, nor by equal access to care for those at the highest risk, but by political and financial motives.

This flickering moment in which we have felt the handbrake taken off shows what power insurers hold over the lives of millions of Americans who contend with the daily threat of our healthcare-created overdose crisis. How blind to this we all have been.

Now that these needless barriers to care for the most vulnerable in our communities have been removed, we must fight to make this permanent.

Justine L. Waldman, MD, the founder, CEO and medical director of REACH, and Judith L. Griffin, MD, its director of research, both contributed to this article.

Photo by Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam/15th Medical Group via FE Warren Air Force Base.

Show Comments