On June 20, the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (OSHA) approved the state’s first regulation protecting indoor workers from extreme heat. An estimated 1.4 million people, including some of the state’s most vulnerable workers, will be covered by the new regulation. OSHA got it over the finish line at the expense of tens of thousands of vulnerable workers who are forced to work for around 10 cents an hour, often in extreme heat.

Years in the making, the “Heat Illness Prevention in Indoor Places of Employment” rule will mandate interventions like water breaks, cooling fans and shorter shifts. It could take effect as soon as August. But in April, an eleventh-hour amendment exempted three places of employment from the new protections: state prisons, local detention facilities and juvenile facilities.

Though many reports that have emerged since the change was first unveiled have presented correctional staff as the only workers at risk, the California labor code definition of “employee” includes “[a]ll persons incarcerated in a state penal or correctional institution while engaged in assigned work or employment … or engaged in work performed under contract.”

State law does not offer similarly clear protections for people in county-run facilities.

OSHA has purportedly “begun preparing an industry-specific rule for local and state correctional facilities, taking into account the unique operational realities of these worksites.” There does not appear to be a deadline.

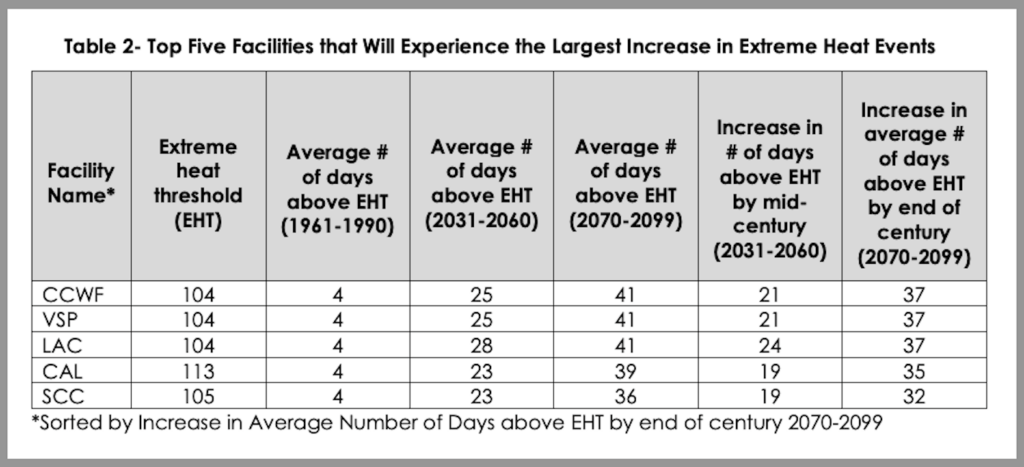

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) currently operates 33 adult state prisons. Research has indicated that 18 are “particularly vulnerable to extreme heat.”

California is the third state to pass such protections for indoor workers, following Oregon and Minnesota. A separate federal-level proposal for indoor and outdoor workplace heat protections was sent to the White House for review earlier in June.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Sustainability Roadmap

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Sustainability Roadmap

In March, Governor Gavin Newsom’s administration abruptly withdrew support for the regulation, blindsiding stakeholders with claims that implementing it within CDCR workplaces would cost significantly more than expected. CalMatters reported that a CDCR spokesperson said the department would have been forced to “immediately request the Legislature to appropriate billions of dollars for extensive capital improvements.”

The board voted to approve the rule anyway, but the governor’s office was adamant about the unacceptable expense. At a hearing in April, OHSA head Eric Berg stated that the agency was advancing the regulation with “a narrow exemption” for correctional facilities.

In 2022, Newsom’s administration shot down another proposal claiming that it would cost CDCR billions of dollars.

The approval comes as a push to end forced labor in California is making its way through the state Senate.

Under current law, “involuntary servitude” is permitted as a form of punishment. A number of other states, as well as the United States Constitution, share this language. The bill ACA8: Slavery would amend state law to prohibit slavery in any form. It would not end the practice; while it would prohibit CDCR from sanctioning prisoners for refusing work, they could still be coerced into work to afford basic needs like food.

The measure was in the Senate Appropriations Committee at publication time.

When it was first proposed in 2022, it supported paying prisoners minimum wage. Newsom’s administration shot down that earlier version—warning that it would cost taxpayers billions of dollars for CDCR to make such a change.

Photograph of Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility and inset graphic via California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation