Nearly five years after California voters legalized marijuana, potentially hundreds of thousands of residents still have publicly available cannabis-related criminal records that the law requires to be sealed—even though the state passed a bill to address this three years ago. While this continues, people’s cannabis convictions can still be searched by employers and police, leaving them vulnerable to discrimination and targeting.

Former Governor Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 1793 into law in September 2018. Known as the “Bonta bill,” after its lead sponsor (current Attorney General Rob Bonta), this created “automatic sealing” for cannabis criminal records. It required prosecutors in the state Department of Justice to review records dating back over 40 years, and was meant to provide justice for people who’d been arrested, convicted or sentenced on charges that would no longer apply post-legalization.

But the deadline for California to complete this sealing process—July 2020—passed over a year ago. And California residents, advocates and officials reached by Filter confirmed, to different degrees, that the state has failed to honor its promise to provide justice for people with cannabis records, who are disproportionately people of color. Disappointingly, even California government officials can’t give exact details on how many people are affected.

Expunging a record usually means it is permanently destroyed, while sealing—which is what California does—merely hides it from public view or from being searched. In either case, it’s an urgent need.

Having a criminal record makes it legal for employers, banks and schools, among others, to discriminate against you. There are over 44,000 different forms of sanctioned discrimination against people with records, in all areas of life. And the dangers are even greater for immigrants in the US; a simple drug possession violation can subject undocumented immigrants, and even legal permanent residents, to deportation.

In California, the legal non-medical cannabis market is already valued at $5 billion and growing fast. It is absurd that while businesses can sell cannabis as legally as an iPhone, people can still have their cannabis records searched when applying for a job.

Why Advocates Sought Automatic Record-Sealing

Perhaps the biggest barrier with expungement and sealing in general is that too many people with cannabis records remain in the dark about this whole process and what their rights are. That’s why advocates call for legislation like the Bonta bill, making the process automatic.

“Expungement is not really straightforward,” Felicia Carbajal, programming director for National Expungement Works (NEW), told Filter. NEW has worked for over three years to share education and support for expungement all over the US.

“So many people don’t know that they’re eligible,” she continued. “I imagine a lot of the folks who have those convictions aren’t running to their local agencies to get this taken care of, nor are they taking it upon themselves to do it because it is arduous. It’s not an easy process if you’ve never filled out forms or if you’re operating from a space of trauma. Many times people from historically-underserved communities get so underwhelmed when they’re put in these situations.”

California offers the option of sealing your record manually. But this puts a burden on impacted people. Carbajal noted that someone in Los Angeles County might have to pay $200 in various fees to seal a record, in addition to extra costs like missing work, paying for gas or obtaining legal support. “If folks have to decide between eating and taking care of an expungement … it’s not a priority.”

The difficulties of manual record sealing, especially for low-income residents, led to the movement for “automatic” sealing in California. Governments that now admit the injustice of marijuana prohibition ought to do the hard work to clear these records, goes the reasoning—not impacted people.

Despite the software’s convenience, there are problems algorithms can’t yet solve, like political stonewalling.

In January 2018, months before California’s legislature passed the Bonta bill, then-San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón became the first in the state to jump-start the automatic sealing movement. He announced his office would take action to seal and reclassify thousands of cannabis records dating back to 1975.

In May 2018, Gascón’s office partnered with Code for America, a digital technology nonprofit. The company developed a software, “Clear My Record,” which vastly sped up the process: It reads thousands of criminal records, identifies those eligible for sealing, and submits them to the DA in a matter of seconds.

This innovation has helped DA offices throughout California—and in other states like Illinois—to process tens of thousands of cannabis records at a time. But despite its convenience, there are problems algorithms can’t yet solve, like political stonewalling.

Why Has Automatic Expungement Ground to a Halt?

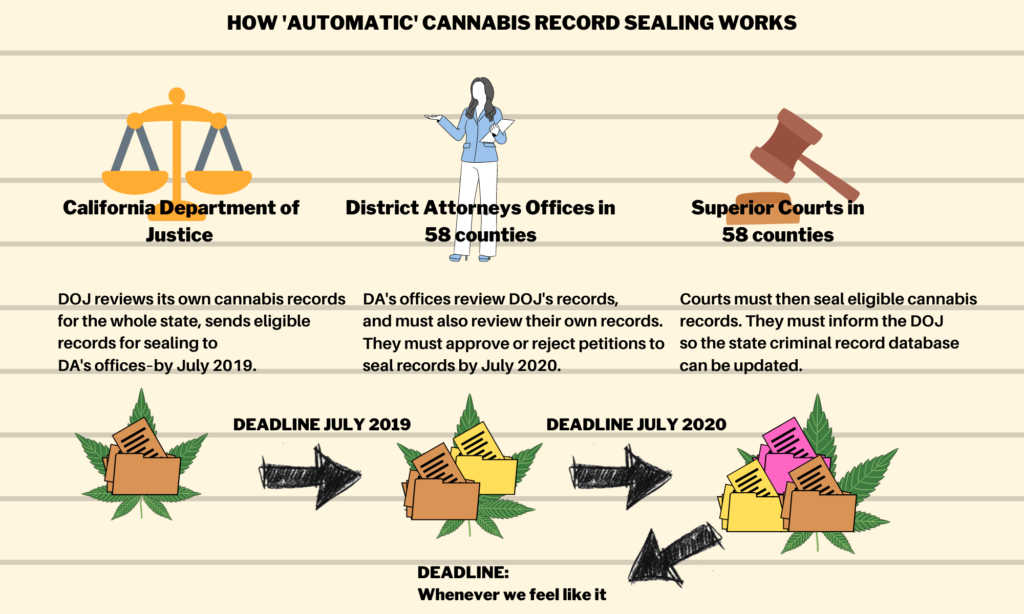

Here’s what was supposed to happen under the Bonto bill.

First, the DOJ was required to identify which records were eligible for sealing, and which sentences could be reduced. The state’s courts estimated about 220,000 cannabis convictions, in total, would be eligible.

The DOJ was then required to file a petition for each eligible case—a request to seal a record or reduce a sentence—to district attorneys in each of California’s 58 counties, by July 2019.

The DAs then had one year to approve or reject these petitions, by July 2020. Finally, county courts would have to seal the approved records and inform the DOJ, whiich would then update its own database of records.

“Nobody knows—I don’t care who you ask, that’s the answer.”

So what has gone wrong with a process designed to protect hundreds of thousands of people?

“Nobody knows—I don’t care who you ask, that’s the answer,” William Armaline, human rights director at San José State University, told Filter. “We don’t actually know right now the status of these clearance efforts across the state.” Armaline was part of the local movement that fought to seal over 11,000 cannabis records in Santa Clara County.

Nonetheless, sources described to Filter some of the various different causes, and potential causes, of this failure. These include inaction from county courts, and the COVID-19 pandemic slowing down government functions.

Record-Keeping Differences Cause Chaos

The California Department of Justice (DOJ) keeps a “criminal record repository” where it records each person with a record throughout the state. County trial courts, meanwhile, keep records of specific cases.

So if someone were convicted of three misdemeanors in Los Angeles County, there would be one record at the DOJ which lists those three convictions—but three different records in the LA court system. Even if the DOJ seems to have largely fulfilled its first obligation of filing petitions to the counties, the sheer complexity of matching records from these different systems seems to have been one factor in the delay.

“There are aspects of record-keeping in California that made this all incredibly complicated to do and measure in terms of finding the status of this,” Armaline said. “There is differentiation between records held at DOJ, and various forms of records held in the individual counties that have different histories in terms of records.”

“Some [counties] have records older than others, some have old paper systems, others got rid of it … the differences are boringly long and complicated.”

Others who have worked with the counties agreed. “There is definitely room for error in the record-keeping, given there are multiple places where the records are held,” Alia Toran-Burrell, an associate director for Clear My Record, told Filter. “Ideally, what is in the courts’ records matches the DOJ’s records, but that’s not always the case.”

And those who work for the counties also shared this concern. “Record-keeping agencies like ours went through different systems in time,” Ruben Marquez, assistant public defender for Los Angeles County, told Filter. Marquez worked with the LA DA’s office to clear over 66,000 cannabis records. He estimates over 90 percent of them were felonies.

“One of the issues we had to keep circling back on was identifying all the potential eligible cases for dismissal,” he said.

And different counties have taken different approaches to these problems.

“There are a ton of paper records,” Toran-Burrell said. “Courts we know are dealing with that in various ways. Some felt like they need to take those paper records and digitize them in order to clear them. Other courts are contemplating not doing anything with the paper records because for background check purposes, people are not accessing the paper records … so it’s less of a barrier for folks. If the paper records are not impeding people’s lives … nothing would need to be done except for court staff not to disclose them.”

Are District Attorneys Dragging Their Feet?

Since September 2019, Clear My Record has been available for all California district attorneys to use free of charge. Toran-Burrell estimates that about 40 percent of the state’s DAs have used the tool. Some chose not to, she said, simply because they have their own record-keeping processes. Asked if any of the DAs were resistant in any way towards doing this work, Toran-Burrell had nothing bad to say about them.

However, California’s DAs have sometimes worked hard to delay record-sealing. In Santa Clara County (San José), for example, DA Jeff Rosen refused for years to clear 11,500 cannabis records, ignoring local activists and even turning down free help from Code for America. He finally acted to seal the records in April 2020, at the height of the pandemic.

And in Los Angeles, former DA Jackie Lacey objected to the sealing of over 2,100 cannabis records. She argued they weren’t eligible, based those people’s prior convictions for other offenses. The public defenders’ office has objected—but even with a new DA in place, the problem isn’t fully resolved. (The new DA, ironically, is George Gascón, formerly of San Francisco.)

How many other counties throughout California have also made such oversights? It’s impossible to know.

“A number of those cases, we’ve continued working with the DA’s office and have gotten them dismissed,” Marquez said. “There are some remaining, but we’ve continued to talk with their office. It is our hope the new DA leadership will dismiss the smaller number of remaining cases.”

Just to show how confusing all of this is: On September 27, 2021, Gascón’s office announced it had identified about 60,000 eligible cannabis records dating back 30 years in Los Angeles County. These county records are separate from the 66,000 records that former DA Lacey addressed, which were only taken from the state DOJ database.

That means roughly twice as many cannabis records should have been sealed as the former DA actually acted on. How many other counties throughout California have also made such oversights? It’s difficult to know.

The Courts’ Delays

Toran-Burrell believes that DA’s offices throughout California have largely done their job to approve (or reject) cannabis records for sealing. The last hurdle is the courts, she said.

Marquez agreed with this, and speculated that the failure of the courts to act—together with the failure of the DOJ to update its own records in cases where courts have sealed records—has delayed justice for thousands.

“It’s theoretically possible that the DOJ met its burden in notifying the prosecution, the prosecution met its burden in notifying the public defenders offices in terms of what charges if any they would object to, and that cases were dismissed by the [local county] court,” he said. However, “It’s possible that there were delays by the [county] Superior Courts in updating their records, and it’s possible there were delays by the DOJ in updating their records.”

“We were hoping courts would prioritize clearing records; we just don’t know if that’s happened.”

“The law did not give a deadline to courts,” Toran-Burrell said. “It just said courts have to update their records […] Assuming district attorneys have done their role, it’s now in the courts’ hands.”

“Last year we tried to reach out to courts to find out the status of record clearance and it was pretty challenging getting info from courts about what’s going on,” she continued. “We acknowledge of course that COVID has been a massive challenge for everyone … at the same time, given the economic implications of COVID, people’s records being cleared is super-important for economic recovery. We were hoping courts would prioritize clearing records; we just don’t know if that’s happened.”

Court representatives from Fresno, San Bernardino and Orange Counties did not respond to Filter‘s requests for comment by publication time. All three counties have currently or previously banned nonmedical cannabis sales, as have over half of counties statewide.

After publication, the three courts contacted Filter. The Orange County Court said that the local DA’s office completed its petition to seal thousands of cannabis records, which the court granted. The court notified the state, as required. But for cases that could not be identified in its system, it returned them to the DA for further action.

The Fresno Court told Filter that it had sealed about 3,000 cases. The county’s DA objected to 258 other cases, “and the parties were notified.” The court notified the state about all records sealed successfully.

The San Bernardino Court told Filter that it had received about 5,500 cases eligible for sealing. But it hasn’t acted yet. “The court will begin processing them in early November 2021,” a representative wrote by email. “There was a delay due to the partial court closure, resulting backlog, resource impacts related to COVID (i.e., staff absences, illness, quarantining, etc.), and severe budget reductions.”

The Path Forward: Will Lawmakers Take Action?

Reached by Filter, a press representative of the California Attorney General’s Office declined to give specifics about statewide progress on marijuana record-sealing.

“We defer to local agencies on the status of these updates and the challenges they are facing,” they said. “We are also unable to speak to what is being released by local agencies, but for awareness, none of our records are publicly searchable.”

Filter also contacted the Judicial Council of California, which oversees the state’s court systems.

“We don’t have this info—you’d have to go to each of the state’s 58 courts,” said Peter Allen of the Judicial Council. “Issues courts have identified to us include processing delays associated with the pandemic, such as receiving data from the DOJ or safely pulling old case records from off-site storage.”

Allen confirmed that some courts have had trouble retrieving older criminal records, while others are working to electronically report records all at once.

According to a December 2018 budget document obtained by Filter, the Judicial Council estimated that about 220,000 marijuana convictions in the entire state would be affected by the Bonta bill. They requested from the legislature a total of about $17 million spread over two years, to help county courts pay the costs of processing marijuana record clearance and reduction. The legislature agreed to the full budget request.

The money and tools for California to fulfill its promise would doubtless materialize if the political will existed.

The path forward from here is unclear. It’s possible the only solution is for the legislature to somehow force the courts to complete this process. The same Rob Bonta who first wrote the expungement bill is now California’s top law enforcement official—potentially a powerful platform to help finish the job he started. And Governor Gavin Newsom, who just won a divisive recall election to keep his job, could also go to bat on this issue for his voters.

The money and tools for California to fulfill its promise would doubtless materialize if the political will existed. Its leaders just need to focus on the problem—for the sake of all the people who were wrongly targeted to begin with.

Photograph via Pxhere/Public Domain

Update, October 14: This article was updated to add information provided after publication by the Orange County Court.

Update, October 20: This article was updated to add information provided after publication by the San Bernardino and Fresno County Courts.

Show Comments