The Biden administration has again voiced support for ending a law that punishes possession or distribution of crack cocaine far more severely than for powder forms of the drug. “The current disparity is not based on evidence,” acting ONDCP Director Regina Labelle told Congress on June 22. “It has caused significant harm for decades, particularly for individuals, families and communities of color.”

Biden himself played a key role in establishing this disparity in the 1980s, during his time as a US Senator. In the decades since, it has resulted in federal courts overwhelmingly imposing draconian sentences on Black Americans for crack convictions—despite the fact that most crack users are white.

Crack and Powder: A Shameful History

Cocaine, a stimulant that can be snorted, smoked or injected, is derived from the coca leaf, through a chemical process that produces a powder salt form of the drug. “Crack” cocaine became increasingly popular in the US in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s. It is made by cooking power cocaine with baking soda and breaking it apart to get “rocks” that can be smoked. Sold in smaller quantities than powder cocaine, it could be more cheaply accessible, helping crack to become widely available in the 1980s.

The crack/powder cocaine sentencing disparity became law in 1986 as part of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, signed by then-President Ronald Reagan. Biden sponsored and co-authored the bill. The law changed federal criminal law around cocaine, to treat possession of crack 100 times more harshly than the possession of an identical quantity of powder.

It never made sense. But Biden and other politicians argued in the 1980s that this was necessary because crack was uniquely dangerous and addictive. In fact, crack and powder cocaine have no pharmacological differences; the effects are almost identical, expect that the mode of ingestion for crack (smoking) tends to give a faster-acting, shorter-lasting high.

Of course, politics doesn’t need to follow science—just the fears of voters. Thus, this 100:1 sentencing disparity remained in law for 24 years. It was reformed in 2010 when President Barack Obama signed into law the Fair Sentencing Act; the bill reduced the disparity, but still left it at 18:1.

Years later, in 2018, the First Step Act, signed by President Donald Trump, made that reform retroactive—meaning that anyone convicted for crack before 2010 could now ask for a sentence reduction. But the 18:1 disparity remained.

The EQUAL Act

Biden pledged to finally repeal the crack disparity in his presidential election campaign. He has now publicly acknowledged that the policy he crafted has had a racist impact, and characterizes his new position as in line with his stated racial justice goals.

He could soon have his chance to follow through. The Senate Judiciary Committee is considering—or at least, holding hearings—on the EQUAL Act, sponsored by Senators Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Corey Booker (D-NJ). The bill would completely end the crack sentencing disparity.

When Labelle made her statement to the committee on June 22, it was also notable that former DEA director and current Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson (R) testified in support of the bill.

Of course, President Biden wanting something and it becoming law are two very different things. It seems likely that this bill could pass the Democrat-controlled House, which last year already voted on a bill to legalize marijuana federally. Whether it passes the Senate is far less clear. Republican Minority Leader Mitch McConnell has shown no interest in supporting the marijuana bill, so one can only guess how he would feel about the crack reform.

It is unlikely the bill could pass with no Republican Senate votes. Given a likely Republican filibuster, Democrats would currently need at least 10 additional Republican votes. Nonetheless, the Republicans did support a criminal justice reform package when Trump was in office—so it’s unclear how this could shake out.

The Ongoing Cost to Black Lives

The crack disparity has wreaked well documented racist harms, from its implementation up until the present day. Department of Justice statistics from 2015 show that Black Americans made up 88 percent of all people in federal prison for on crack charges. Sentences for crack convictions were longer than for any other drug—on average, 14 years in prison.

Although 99 percent of the people imprisoned for all drugs were there for trafficking, we have to question that definition. Up until 2010, possessing just 5 grams of crack was enough to trigger a mandatory five-year sentence for trafficking. After Obama’s reform, that threshold was raised to 28 grams.

Too little has changed in the years since. A US Sentencing Commission report from 2020 showed that Black Americans were defendants in over 76 percent of federal cases involving crack.

The proportion of Black people who are prosecuted in this way is wildly out of step with the proportion of Black people who actually use crack. Research on drug use trends shows that Black people are less than 1 percent more likely to use crack than white people. And the majority of crack cocaine users are white. So the fact that Black people, who comprise around 13 percent of the US population, are targeted by 76 percent of federal crack cases speaks volumes about drug-law implementation.

Removing the crack/powder cocaine sentencing disparity is long overdue. It is also nowhere near sufficient—while punitive drug policies in general remain, and when no restitution has been made to Black communities devastated by the racist drug war.

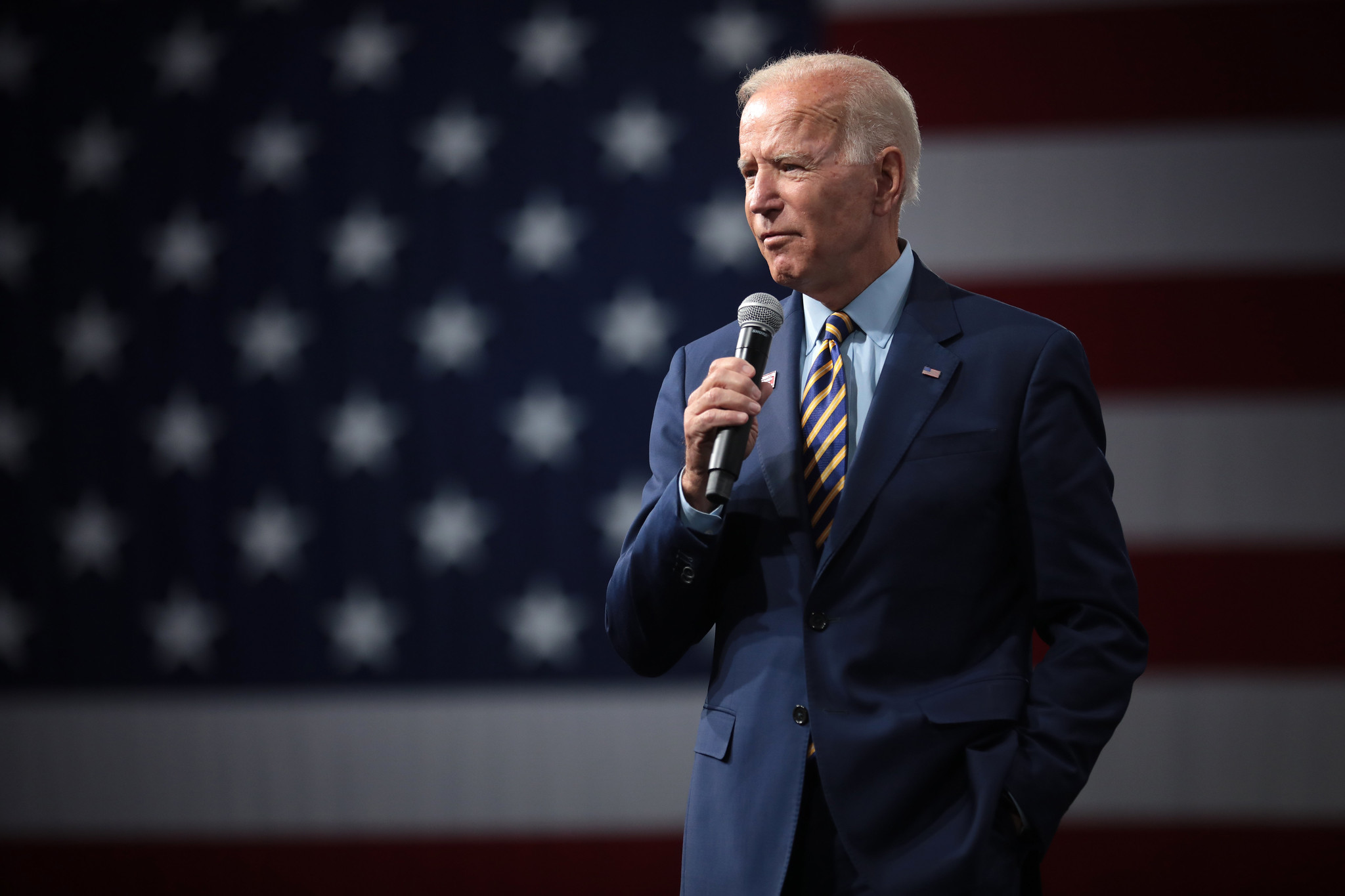

Photograph of Biden in 2019 by Gage Skidmore via Flickr/Creative Commons 2.0

Show Comments