The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is not only continuing to incarcerate people past the point when they should have been transferred to a contracted halfway house, but is unable to estimate the scale of the problem. The agency also rarely pays contractors on time and routinely fails to apply sentence reduction credits that prisoners have earned toward earlier release, according to a February audit by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

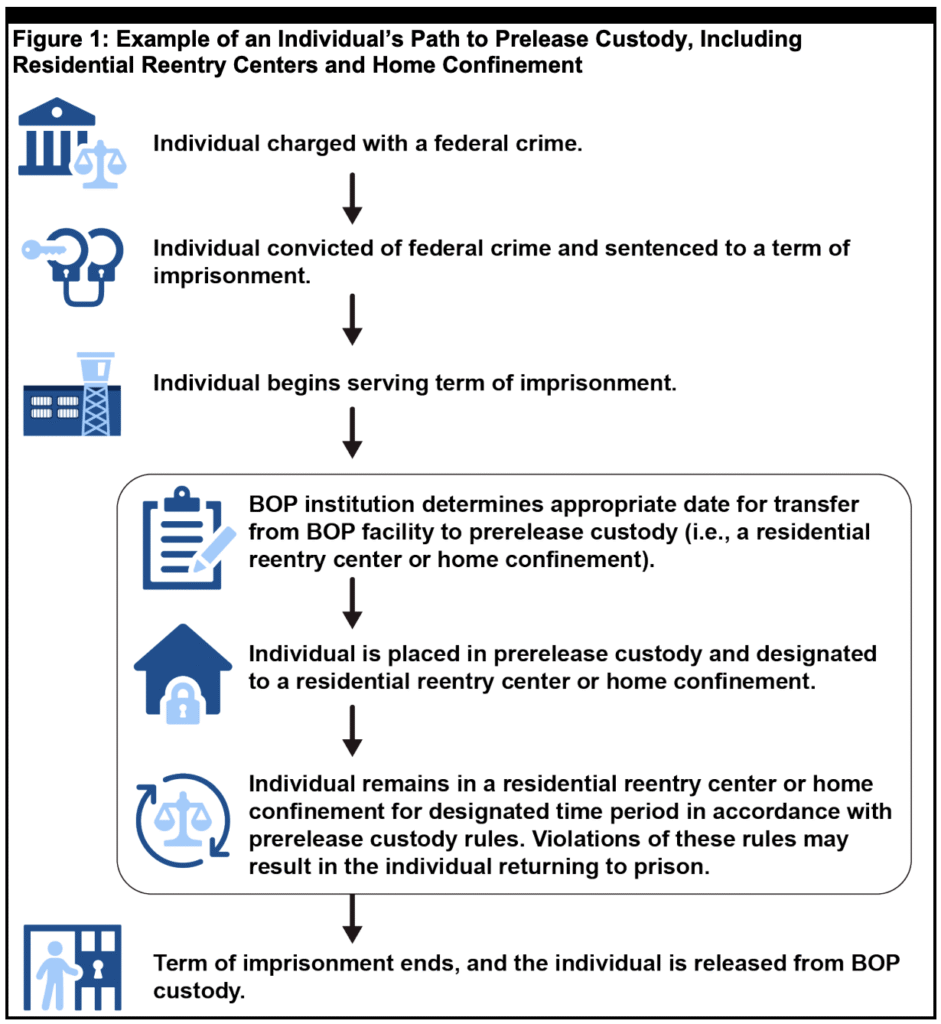

Around 155,000 people across the United States are incarcerated by BOP. Those approaching the end of their sentences are often eligible to complete the last portion out in the community under some form of “prerelease custody,” like electronic monitoring. The GAO report covers halfway houses, formally known as residential re-entry centers (RRC) as well as home confinement overseen by RRC staff.

As of May 2025, BOP contracted with 155 RRC to house around 8,500 people and supervise another 3,400 or so on home confinement—about 8 percent of the BOP population altogether. RRC are required to provide various re-entry supports like job training, while subjecting supervisees to drug-testing, curfew and other restrictions.

“Although BOP officials acknowledged that there have been individuals in prison who could have transferred to an RRC or home confinement, the bureau does not know the scale of this issue,” the report states. “BOP officials told us that they could not answer the question [of how many eligible people are still in prison] because the data is not readily available … because eligibility dates are documented in the individual records of incarcerated people, rather than a trackable information technology system.”

BOP attributed the situation to lack of RCC bedspace. But investigators noted that the agency “does not know the full extent of this shortage” either, because it has not actually assessed RCC capacity.

The First Step Act of 2018 requires BOP to maintain sufficient prerelease custody capacity for everyone eligible. Access to RRC or home confinement is also mandated for some prisoners under the Second Chance Act of 2007.

“Until BOP maintains and monitors such data, it cannot ensure individuals transfer on time and take corrective action when timely transfers do not occur,” the report states. “As a result, BOP cannot ensure individuals receive the services and have the opportunities available at an RRC or home confinement, such as finding employment and long-term housing and reconnecting with the community.”

As of September 2024, BOP was only utilizing about 91 percent of RRC capacity, but 121 percent of home confinement capacity (RRC staff are often able to supervise a higher number of people on home confinement than their contracts require them to).

One barrier is that available RRC space isn’t necessarily located in the areas where people are set to be released, and the point is for people to be able to rebuild ties in their communities. But again, because BOP hasn’t adequately assessed RCC capacity, it doesn’t know which regions need more bedspace, or how much more, or how much it all might cost.

Nor does it appear the agency is looking to maximize the existing capacity. Out of nearly 30,000 cases reviewed, GAO found that 21,190 people had “earned time” that BOP had not actually applied toward their release dates, despite being legally required to do so.

This refers to sentence reduction credits—for example, for every 30 days of “successful participation” in programming like Alcoholics Anonymous or other activities that purport to reduce recidivism, people in custody can be credited 10 or 15 days off their sentence.

Compounding the problem, BOP rarely pays contractors on time. From 2022 through March 2025 the agency made approximately 65,000 late payments, racking up $12.5 million in late fees. In 2023 and 2024, about 70 percent of payments to RRC were late.

“RRC staff said they face hardships due to the late payments—needing private loans to pay staff,” the report states. “One RRC representative said late payments have made some RRCs reluctant to bid for new BOP contracts, which can further complicate BOP’s plans to expand capacity.”

RRC and home confinement are both cheaper than confinement in prison.

Top image (cropped) and inset graphic via Government Accountability Office