John (not his real name) was a regular on the Avenue. A biracial man in his late 20s, he was one of a handful of unhoused people who sleep on cardboard boxes and use drugs in the shadow of the Constitution Medical Plaza in South Philly. It’s where the nonprofit group Safehouse planned to open the nation’s first sanctioned safe consumption site before being run out by angry locals.

John’s drug use varied. He regularly smoked crack cocaine and marijuana, but avoided opioids. Since moving last year to South Philadelphia—a neighborhood second only to Kensington in Philly overdose fatalities—I regularly met John outside the subway stop or the local bodega where he panhandled. Our short conversations and shared cigarettes gave me my first foothold into the insular drug subculture of South Philly, so different from my usual beat in Kensington.

Then, in early August, I stopped seeing John. It was several weeks before he returned, having visibly gained weight. He told me he’d been in rehab and was looking for a recovery house to take him. I later learned from one of John’s confidantes that he had been arrested for drug possession and spent several days in jail, before being transferred to a court-ordered treatment program—stigma must have stopped him disclosing that.

At the time of his arrest, John was regularly smoking crack. But during his confinement he began regularly using Suboxone—the buprenorphine-naloxone combination widely prescribed to treat opioid addiction—despite not using opioids previously. He continued using it after his release.

Until recently, I had never met a Suboxone user who didn’t previously or concurrently take another opioid.

There has been an abundant market for Suboxone on the streets of Kensington for several years, as I’ve reported for Filter. And some municipalities, including Philadelphia, have begun dropping criminal penalties for possession without a prescription. But until recently, I had never met a Suboxone user who didn’t previously or concurrently take another opioid.

Those I spoke with in Kensington all used Suboxone in the context of their other opioid use. For some, it was just the next best option at times when heroin and fentanyl were less available. Many employed the partial opioid agonist in a practice known as “chipping”—using heroin only occasionally while filling in with Subs. Others bought Suboxone on the street for the purpose for which it’s widely prescribed—to help them recover from an opioid addiction when they lacked access to healthcare providers, or perhaps to supplement a prescribed dose that they found too low.

It was disconcerting to begin meeting people for whom Suboxone was their first opioid, when harm reduction advocates (and I) have often maintained that no such market for diverted Subs exists. Yet the fact that it does exist—on however small a scale—doesn’t change the fundamental point that diversion is nothing to fear.

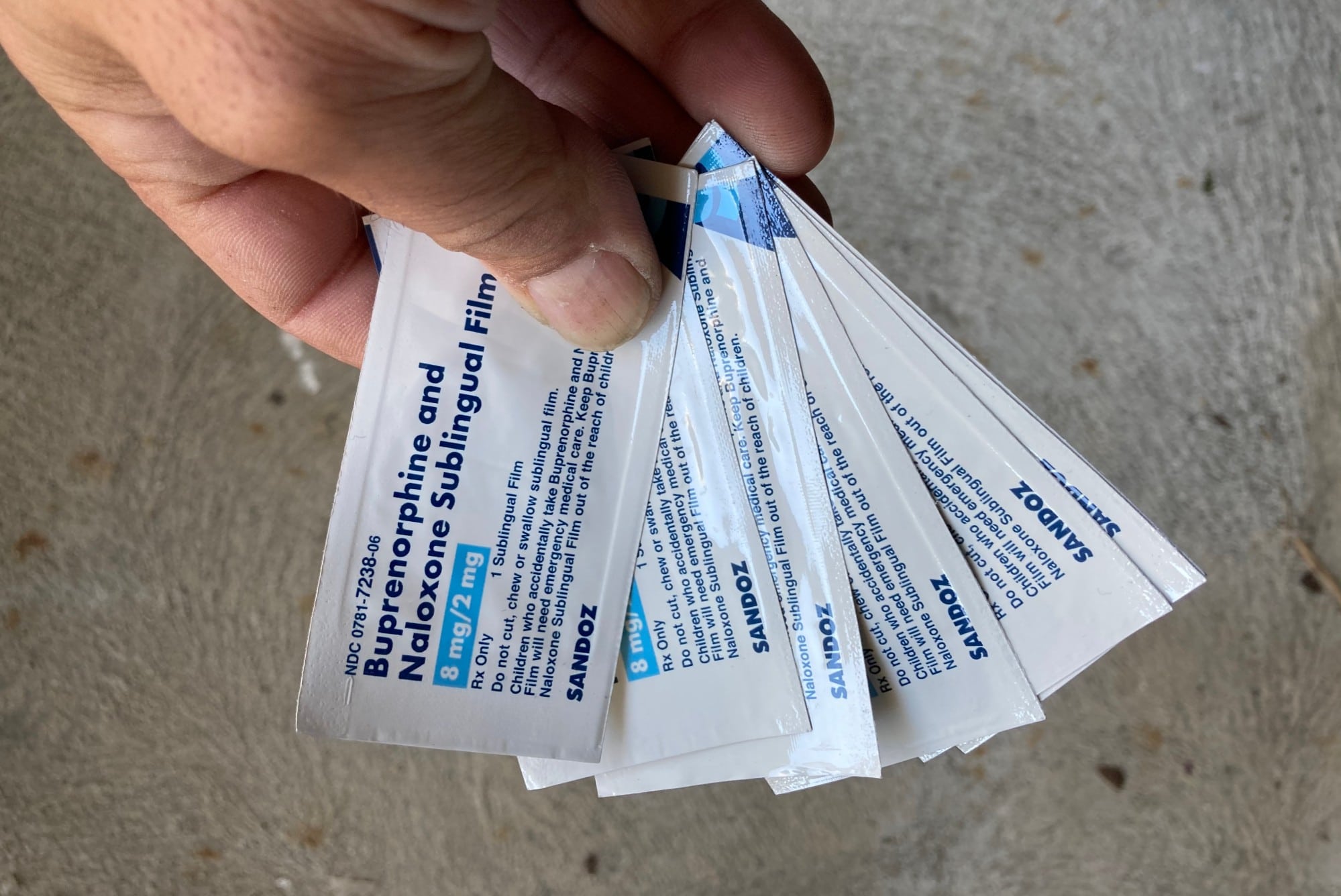

The reasons for its emergence are complex, but a significant factor is the ease with which Suboxone, thanks particularly to its sublingual film form, is smuggled into jails and prisons—and then concealed and divided once inside. Together with synthetic cannabinoids (called “deuce” on Philly street corners), Suboxone is anecdotally the favorite drug in Philadelphia County’s carceral settings.

Formerly incarcerated people have told me that a single strip of Suboxone, or one of its generic rivals, retails for $80 inside, representing an enormous profit margin for those who provide it. I once met a grandmother who would smuggle in the thin strips during visits with her son in state prison. “It’s easy, they never check under here,” she said, pointing to her breast.

Once inside, the strips are cut into smaller pieces which are taken orally, or else dissolved in water and snorted. The euphoric effects of buprenorphine on a person without opioid tolerance are indistinguishable from other prescription opioids. Regular use can lead to physical dependency. So released people, as they have recently described to me, have been returning to the streets with a taste for the orange films, which are sold up and down Kensington Avenue and on street corners across Philadelphia.

But incarceration isn’t the only factor. Around the time John found himself in handcuffs and on his way to rehab, I got a call from Nas, a Kensington resident, complaining about a hike in Suboxone prices there.

“Man, I just paid $15 for a strip,” Nas told me—a 50 percent markup from the usual $10. “And it took me forever to find anyone with Subs.”

That surprised me. Before I was forced to retreat into coronavirus-induced quarantine with the rest of the city, diverted Suboxone was so abundant in Kensington that sellers would practically trip over each other to make a deal. What Nas was telling me seemed impossible.

So I recently returned to Kensington Avenue to see what was happening. Sure enough, there were visibly fewer people selling Suboxone. However, I did find that prices were reliably still $10 a strip (which, it’s worth noting, is the medication’s retail price in pharmacies across the city).

But evidently something was going on. The shouts of “Subs! Subs!” that were ever-present around the transit stations of North Philadelphia had noticeably quietened. One day this month, I encountered just one person hawking Suboxone—which is still illegal to sell, although possession was effectively decriminalized by District Attorney Larry Krasner at the beginning of the year.

It was tempting to draw an easy connection between that reform and the apparent shortage of street Suboxone, but that would be naive. I have seen countless drug corners reopen moments after a raid, and not a single person I know factored marijuana decriminalization into their decision to smoke or not.

“At least you know what you gettin’.”

So I went to the best place I could think of for answers.

“B” is a 32-year old aspiring rapper who sells Suboxone to supplement his income as a dishwasher. He’s very tuned into the dynamics of Kensington’s drug markets, which have changed rapidly since 2017, when the closure of “El Campamento” pushed drug selling eastward from West Kensington onto corners manned by mostly Black freelancers, who, like B, frequently commute to work (in his case from West Philadelphia).

“Young Black men grow up seeing fiends on the block buying dope [heroin] and hard [crack], so they draw a hard line between those drugs and pharmaceuticals like Percocet and Adderall,” said B, who takes Adderall himself. “At least you know what you gettin’.”

But the introduction of prescription monitoring databases has made prescription fraud and doctor-shopping harder. Thirty milligram oxycodone pills, long a favorite among pharmaceutical opioid users, have shot up in price recently, B said—from an already-pricey dollar per milligram to as high as $50 a pill.

Other sources seem to confirm this hike. One contact bragged that she could get me the pills for $25 a piece, “but only for you, and only if you buy the whole bottle.” A different seller told me he recently moved a bottle wholesale at $45 per pill.

With oxy prices so high, B said, and heroin eschewed by many youth of color for its stigma and dangerous adulteration, many people are finding Suboxone an alluring alternative, which means increased demand for the drug. That, combined with potentially large numbers of people coming out of jail who have become habituated to Suboxone, seems to have led to this changing market—one that includes first-time, recreational Suboxone use.

“If more people are taking it, instead of playing Russsian roulette with pills or street dope, that I consider a benefit to harm reduction in the city.”

Again, this is not necessarily a bad thing—and quite likely a good one, as some doctors are happy to point out. If anyone is seeking out Suboxone having never used opioids before, consider what they would likely seek instead if Suboxone were unavailable.

“I hear more people are taking Suboxone, with or without a prescription, and I think good,” said Dr. Joseph D’Orazio, an emergency room physician and addiction medicine practitioner at Temple University Hospital in North Philadelphia.

D’Orazio said he has never had anyone present with a “Suboxone addiction”—and added that buprenorphine’s 24mg a day “ceiling effect,” which makes the drug ineffective in large daily doses, means Subs are just about the safest drug sold streetside.

What’s more, Suboxone’s tamper-proof packaging and unique sublingual delivery formulation (which was so valuable to Suboxone’s manufacturer that the company fought for years to keep generic versions off the market) all but eliminate the possibility of counterfeit versions and the adulteration and danger they would present.

“I work in one of the busiest emergency rooms in Philly and have never once encountered a Suboxone overdose,” D’Orazio told Filter. “If more people are taking it, instead of playing Russsian roulette with pills that could contain fentanyl or using street dope, that I consider a benefit to harm reduction in the city.”

Suboxone, which was introduced as a prescription drug in 2001, has many benefits. But much about its over-regulated availability, or lack of it, remains deeply unsatisfactory. Some prescribing physicians are reputed to charge as much as $350 for an intake visit, followed by $150 a month for follow-up visits for a medication that, as a Schedule III controlled substance, qualifies for five refills.

If non-prescribed Suboxone uptake increases on any scale, it’s difficult to know what long-term impact that might have on use of much riskier opioids. Perhaps some people, finding Suboxone unavailable or unsatisfactory, will move to other opioid alternatives. But for the time being at least, the little orange strips are likely saving the lives of Philadelphians who would otherwise be taking much bigger gambles.

Photograph by Christopher Moraff

Show Comments