On the first day of 2020, around 800 New Yorkers will be released from Rikers Island as historic state bail reform legislation passed this year takes effect. The eyes of advocates and health service providers widened when this figure was presented at a December 10 conference held at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in midtown Manhattan. The event focused on the the public health impacts of the impending bail overhaul, signed into law as Senate Bill S1509C in April 2019.

Reforms that are highly desirable can simultaneously present practical challenges to public health provision for impacted people. A palpable air of anxiety hung over the attending clinicians, social workers and community health workers who work in New York City’s jails, re-entry programs and community-based organizations.

Olive Lu, the John Jay PhD candidate who presented the data, and other researchers with the Data Collaborative estimated in a September report that applying the new legislation to 2018 misdemeanor cases would have seen release without bail required in 90 percent—or 125,510—of those cases. That would represent more than a 20,000 increase in such cases compared to what New York City actually saw that year.

Lu’s figures cannot be construed as projections for what’s to come later in 2020, but they do make one thing clear: The vast majority of New Yorkers charged with misdemeanors will no longer be detained in city jails simply because they cannot afford to pay for their freedom. And she explained how this could impact public health: The system will likely see a surge in people in need of supervised release services, programs may be strained and defendants will have less time to access services.

Delivering the same quality of supervised release services after the 2020 bail reforms take effect will require sustained client engagement, explained a panel of professionals working in community-based care programs. Social worker Giles Malieckal and the pretrial services team he directs at CASES aim to meet clients where they’re physically at. Going to see clients, instead of solely requiring them to come to the program, is critical to keeping people engaged in services, he said—and that will be even more the case as more people exit jails faster.

Correctional Health Service providers who are based in the jails will have less time to connect with defendants, but the reforms may not have as much of an impact on the operations of Rikers’ Substance Use Treatment program, suggested Dr. Jonathan Giftos, its clinical director, during his panel presentation. “We already operate with the assumption that we won’t know patients’ release dates,” he said, explaining that the program aims to connect eligible people with opioid substitution therapies, like methadone or buprenorphine, as soon as possible.

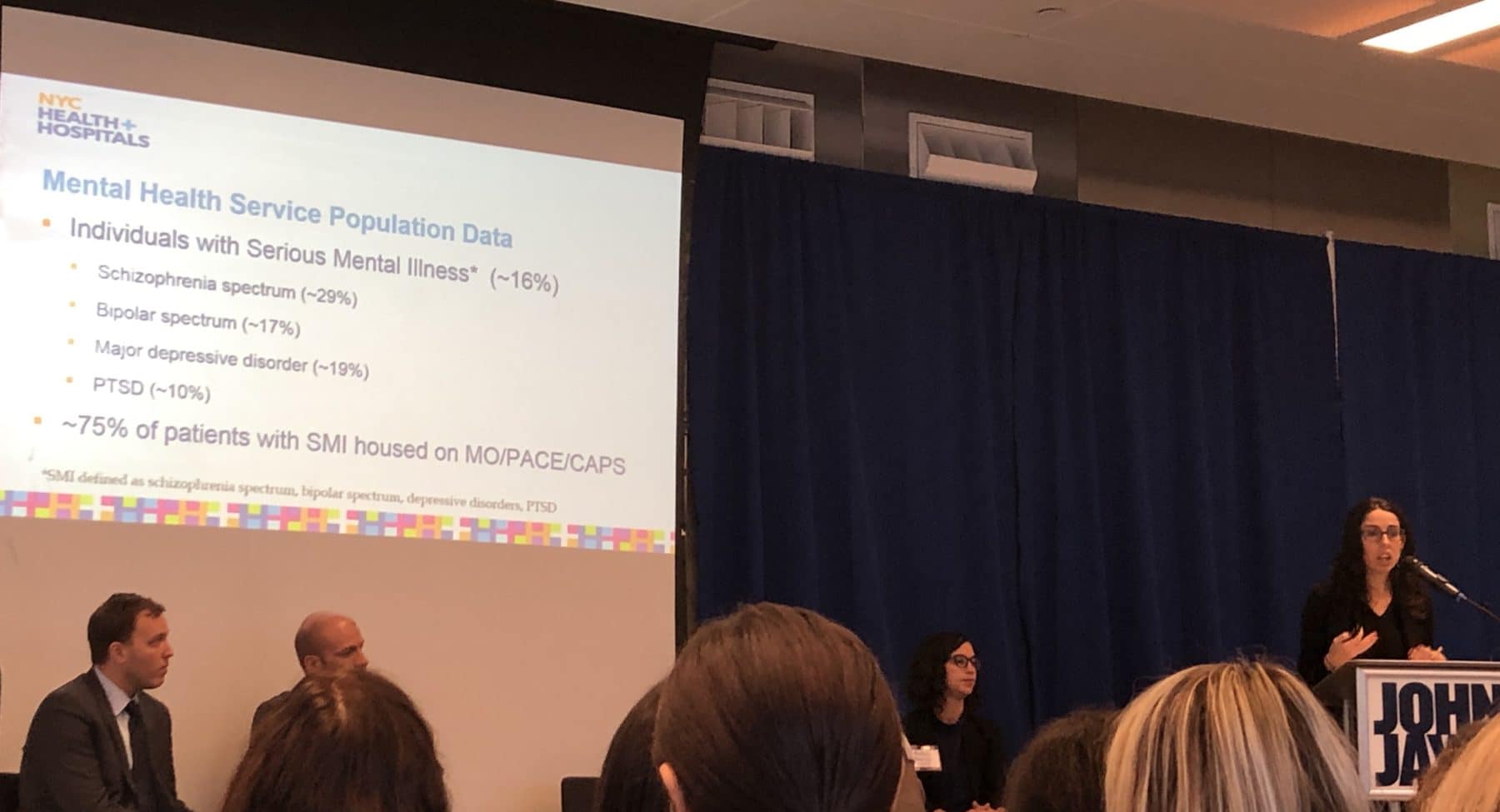

Accessing mental health services on Rikers could be impacted, though. The jail system already sees a disproportionate number of people diagnosed with serious mental illness (16 percent), while the national average was 4 percent in 2018. Dr. Virginia Barber Rioja, a CHS forensic psychologist, told the audience that four additional mental health units will be added to Rikers, which would provide more capacity to see all defendants in a timely manner. Even with the additions to the notorious jail, incarcerated patients frequently don’t even make it to their mental health appointments, as Filter has reported, simply because correctional officers fail to “produce” them.

“As New York moves forward with criminal justice reform,” wrote the Data Collaborative researchers, “it is imperative that we continue to closely track and measure the impacts of these reforms to ensure that they are driving fairness in our system of criminal justice and safety in communities across the State.”

Photograph of Dr. Virginia Barber Rioja presenting at the event on December 10 by Filter.

Show Comments